This is the third post in our multi-part series on the Fed's 2025 framework review. Part 1 can be found here and Part 2 can be found here. The Fed has an opportunity to learn valuable lessons and apply those lessons in a forward-looking manner. By revising its framework accordingly, Fed policy can be more robust in response to supply shocks and more supply-aware in its strategy and communications.

Over the past few years, the Federal Reserve's inflation guidance has shifted so many times that it’s hard to keep up. The Fed prefers to bat away any alternative to inflation targeting, such as nominal GDP or income targeting, under the premise that a nominal aggregate is more confusing to communicate to the public than a price index. But what could be more confusing than the Fed’s inflation communications over the past five years? As the Fed reviews its strategy, tools, and communications for fulfilling its Congressional mandate, they should consider just how messy their characterizations and assessments of inflation have been. Left unchanged, similar shocks are likely to leave the public confused and the Fed exposed, again.

The Fed’s intentions aren’t misguided. Inflation data is noisy. Headline inflation can swing based on volatile components like food and energy. Even core inflation, which excludes those two categories, has been distorted by pandemic-related goods volatility and lagging housing inflation. So the Fed has tried to drill down: What category best reflects underlying, persistent inflation tied to labor market tightness and services demand?

Hence the evolution:

- Transitory was the key word to explain early price surges in goods and pandemic-affected services in 2021, only to be scrapped and mocked subsequently.

- Core Services, excluding goods weighed down by supply chains.

- Core Nonhousing Services, helped remove lagging rent components.

- Market-Based Core Nonhousing Services, stripped out some of the volatile and idiosyncratic components, particularly in financial services

Each step has aimed to get closer to the elusive “underlying inflation” dynamic within the noise. But each shift also raises new questions about what the Fed is actually reacting to.

Aggregation Innovation: How The Fed’s Preferred Inflation Indices Shifted From 2021 To 2025

The Fed’s 2% inflation target is based on the deflator for Personal Consumption Expenditures, better known as "Headline PCE." This represents the the basket of goods and services that American households actually consume in real-time. This index includes volatile prices and every essential item and service. Grocery and energy prices can be volatile, and especially so around energy price shocks. As a result, the Fed tends to focus on “Core PCE,” which excludes the prices of gasoline, energy services paid for through your utility bills, and food paid for at grocery stores.

The reason for excluding such salient prices can get wrapped up in conspiracy, but there is an underlying logic. The current rate of Core PCE inflation is generally a better guide to where Headline PCE inflation will be a year from now, relative to the current Headline PCE inflation rate. Since monetary policy works with long and variable lags, Core PCE inflation is likely to be a better forward-looking indicator for achieving the 2% inflation target over the time horizon that monetary policy affects the economy.

The most recent inflation episode started with a few known factors in early 2021. We knew that key commodity prices, like oil, were recovering from their collapse in 2020, and were likely to strain inflation rates in the short-run simply as a result of prices recovering to their pre-pandemic range. We also knew that services prices and demand were suppressed but poised to recover as the economy reopened and labor markets recovered. In-person recreation and accommodation services saw sharp declines in prices in 2020 only to see a snapback as demand recovered and surged.

But even pandemic-related effects weren’t so simple. They quickly morphed into a more complex set of phenomena that combined demand recovery with supply challenges. New motor vehicle production fell off a cliff due to a global microchip shortage that automakers failed to foresee and understand until global chipmaking capacity was already fully allocated.

With new car production going scarce, used car prices surged. And since used cars aren’t either food or energy prices, their volatility also drove the volatility of Core PCE inflation. As much as economists might assume otherwise, a local scarcity in one set of prices doesn’t automatically reduce prices proportionally for other goods and services.

The Fed assumed that this type of pandemic-induced supply chain bottleneck to the automobile industry was a “transitory” form of inflation. Prices would rise for used and new cars, but otherwise inflation was poised to fall as those price adjustments faded from year-over-year calculations. We also saw in subsequent months how other bottlenecks were emerging across supply chains, and thus the Fed began to understand they were dealing with a bigger and longer-lasting shock. Hence the pivot to focusing on “Core Services PCE” inflation, the services segments of Core PCE that were perceived to be more insulated from the supply chain quirks infecting goods side of Core PCE inflation.

“Core Services PCE” inflation was intuitively associated with “underlying inflation” related to labor market pressures and aggregate demand. When central bankers hear “services,” they think those activities are more labor-intensive and thus the changes in prices are more likely to be driven by the labor market. But even this pivot was laced with problems, some of which the Fed quickly recognized, while others took longer.

Housing rent, the largest component of Core Services, substantially lags in its Consumer Price Index (CPI) and PCE translations, relative to what can be observed from market rents in real-time. The surge in market rents that occurred predominantly in 2021 and early 2022 took multiple years to make their way into the CPI and PCE translations. If the Fed wanted to avoid responding to lagging data, it would need to avoid putting a strong emphasis on Core Services PCE.

And so the Fed shifted yet again, this time to “Core Nonhousing Services PCE,” otherwise labeled as “Supercore.” With bottleneck-infected goods, volatile energy services, and lagging housing inflation separated out, the Fed was supposed to be able to see what “underlying inflation” truly was. Or at least so the Fed thought.

The logic of each separation had a justifiable intuition, but with each bit of slicing and dicing, new imperfections were amplified. Core nonhousing service prices are not necessarily more indicative of labor market or aggregate demand conditions. Some components are in fact highly sensitive to goods-related phenomena that would show up in “Core Goods PCE.” The value of motor vehicles also affects, with some lag, the cost of leasing, renting, maintaining, repairing, and insuring a car, all of which fit within the Fed’s Supercore measure.

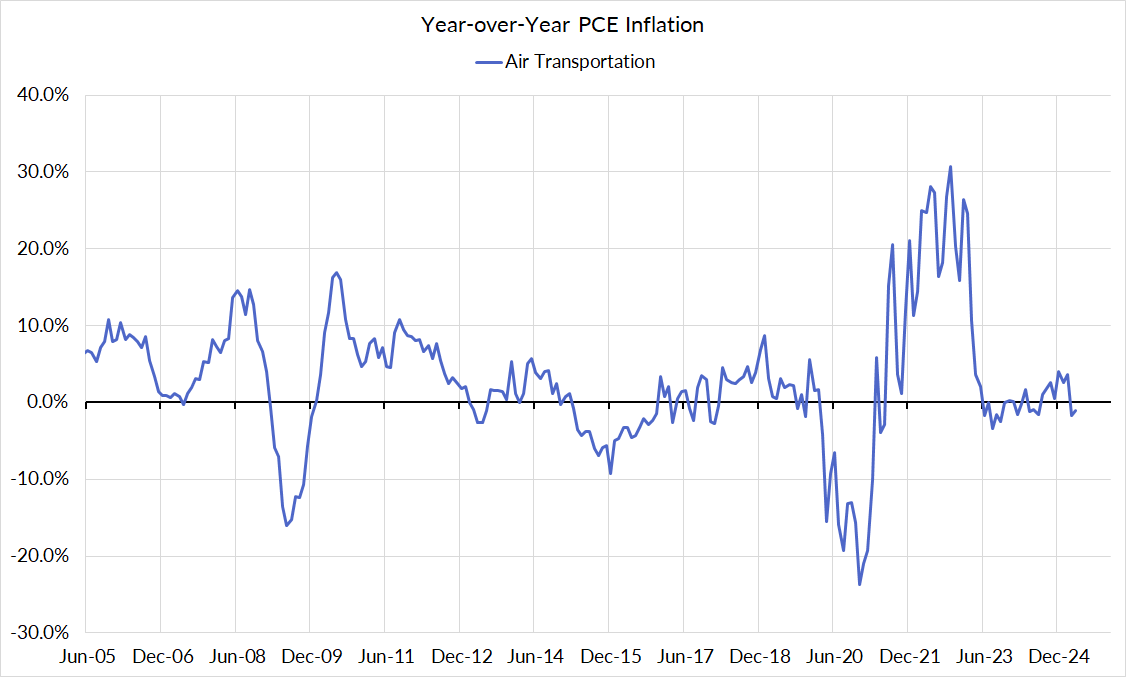

The cost of airfares is substantially related to the cost of jet fuel, which spiked when Russian refining capacity was no longer so readily available following the outbreak of war in early 2022. Food services inflation, which is included in Core PCE,” correlates substantially with inflation experienced at the grocery store, even as grocery store prices are also vulnerable to energy and commodity supply shocks.

Convinced by the elevated rate of Supercore PCE inflation in 2022 and early 2023, the Fed continued to tighten policy, under the impression that it would require a more recessionary labor market to cure the economy of its inflation ailments. Yet as 2023 and 2024 progressed, many of these inflationary pressures were reversing even as the labor market held up remarkably well. It turned out that as vehicle, food, and energy prices fell or even just stabilized, so too could a variety of Core non-housing service prices.

But there were still other categories of inflation that were keeping Supercore from converging to what prevailed when the Fed was previously at its 2% target on Headline and Core inflation. The run-up in the S&P 500, due to resilient growth and AI-related optimism, was pushing up portfolio management services, which tends to be the most volatile component of measured financial service prices.

While the Fed seemingly missed the role of other non-labor Supercore price dynamics, the Fed did take notice of how this financial market dynamic was dominating the month-to-month shifts in Supercore. As we entered 2025, Chair Powell acknowledged publicly that the stock market’s short-run performance was distorting their preferred measure, and used it as a moment to pivot attention to “market-based” core non-housing services, a “Market-Based Supercore.” To address the real distortions tied to commodity price volatility, supply chain bottlenecks, housing inflation lags, and the stock market, the Fed had arrived at a highly refined sub-aggregate of inflation.

The trouble with all of this slicing and dicing is that we are left to analyze a very narrow set of prices. Market-Based Supercore primarily spans service prices in the transportation services, healthcare services, and leisure & hospitality sectors. And even in these three sectors, the scope for energy price shocks to prove relevant, particularly for air travel and food services, remains meaningful.

The Problem With the Slices

At some point, slicing and dicing inflation data so granularly starts to backfire. Each new sub-index introduces its own measurement issues, and none of them are particularly transparent to the public. Economists take it as a matter of faith that these quirks will eventually balance each other out, but recent experience suggests otherwise. Market participants have struggled to keep up with which indicator is "in the driver's seat" of Fed thinking. For everyday households, the communication breakdown is even more severe.

This approach also runs the risk of amplifying unforeseen distortions. In an effort to exclude distortions in one set of segments, the distortions of still-included components are up-weighted. Focusing too much on specific categories that happen to be elevated or stable in a given month while missing the broader dynamics at play. In trying to get clearer signals, the Fed may be constructing ever-narrower indicators that are less representative of the full economy.

There is no perfect component of inflation, though depending on the purpose, some are better than other. If you want a real-time view of inflationary pressure, you should not look at housing PCE inflation. If you want a gauge of labor market heat in the inflation data while accepting some latency, it’s hard to do better than the housing component.

Component inflation data is rich with information for testing hypotheses on the precise causes of inflation, but it is a bad focal point for helping markets and the public understand the Fed’s present and future reaction function.

There Is A Better Way To Approach Inflation Communication

By now, we would hope the Fed and all readers can see that this approach to communication, while locally rational, can lead to absurd destinations. As fellow bottoms-up analysts of inflation data, we sympathize with Chair Powell and the Fed staff. Microeconomic dynamics do matter to the complexion of macroeconomic inflation data, but they make for horribly confusing communication. Worse, they leave the Fed exposed to cheap criticisms that undermine legitimacy and operational independence.

There is a better way forward if the Fed is ready to capitalize on its 2025 framework review, notably called a Review of Monetary Policy Strategy, Tools, and Communications [emphasis added]. For all of the talk about particular subcomponents of inflation, a simpler approach would highlight the role of nominal aggregates. It turns out that through much of 2021 and 2022, the pace of total-current-dollar consumer spending was running at a very elevated pace.

This elevated pace of market transactions for consumer goods and services was also no great surprise. In a period of rapid labor market recovery, the volume of job and wage growth was also elevated. Generally speaking, households’ nominal consumer spending growth is highly related with its primary and marginal funding source: nominal labor income.

With the advantage of hindsight, it’s not hard to see why the US economy was able to stay reasonably resilient and achieve what was an effective soft landing in 2024. Amidst elevated income growth, balance sheet constraints are less likely to bind, even if interest rates move up meaningfully. One can quibble about the speed and scale of interest rate hikes in 2022 & 2023, but the case for aggressive easing of interest rate policy is less compelling when nominal income growth is reasonably robust.

The trouble starts when short run labor market and inflation outcomes diverge. If nominal labor income growth was much weaker even as inflation was still elevated (see 2008), the risk of policy mistakes is higher, as the Fed is more likely to set off nonlinear financial constraints in the name of fighting inflation. Centering communication around nominal consumer spending and nominal labor income would be an effective remedy. It would enable effective causal description while still staying firmly rooted in the Fed’s dual mandate objectives of maximum employment (labor market conditions) and stable prices (inflation outcomes).

For monetary policy to be effective, the Fed needs credibility and clarity. That means having a consistent reaction function and a transparent set of core indicators that inform the public of its decisions. Consumer spending and labor income are substantially more understandable than the thicket of methodologies and microeconomic dynamics that unevenly shape each inflation component.

The Fed's 2% inflation target doesn't need to be abandoned, but given (1) the latency of monetary policy, (2) the longer run nature of that target, and (3) the messy nature of short-run inflation data, the Fed would be wise to revamp the set of short-run indicators and communication devices it relies upon for achieving that goal.