This is the fourth post in our multi-part series on the Fed's 2025 framework review. Part 1 discusses how the Fed can deal with tariff inflation risks, Part 2 discusses the implications of recent productivity dynamics, and Part 3 discusses the Fed's inflation and supply shock communication failures of the past few years. The Fed has an opportunity to learn valuable lessons from the past few years and apply those lessons in a forward-looking manner. By revising its framework accordingly, Fed policy and communications can exhibit more robustness in the face of supply shocks and risks.

High interest rates are supposed to reduce inflation. Taken far enough, they generally will. But financing costs have now remained elevated for a persistent period, and market pricing implies that they are poised to persist for even longer. What started as policy tightening in response to the post-pandemic boom and inflation is now liable to stay in place as a result of new policy-induced inflation risks.

As a result of interest rates and financing costs remaining higher for longer, capital formation in critical interest rate-sensitive sectors is now meaningfully weaker and, in some cases, substantially deficient. Where capital formation is weak, future supply is less equipped to meet demand, and inflation risk looms even larger. Abstract as this might sound, the housing market exemplifies this dynamic. The Fed shouldn't be surprised by market rent inflation in the coming 12 months, but without adjustments to their framework, communications, and strategy, the Fed could be caught offsides on inflation risks yet again. Worse, the Fed's responses may risk aggravating the very inflation risks they seek to address.

If Weak Supply Re-Accelerates Housing Rent Inflation, What Should The Fed Do?

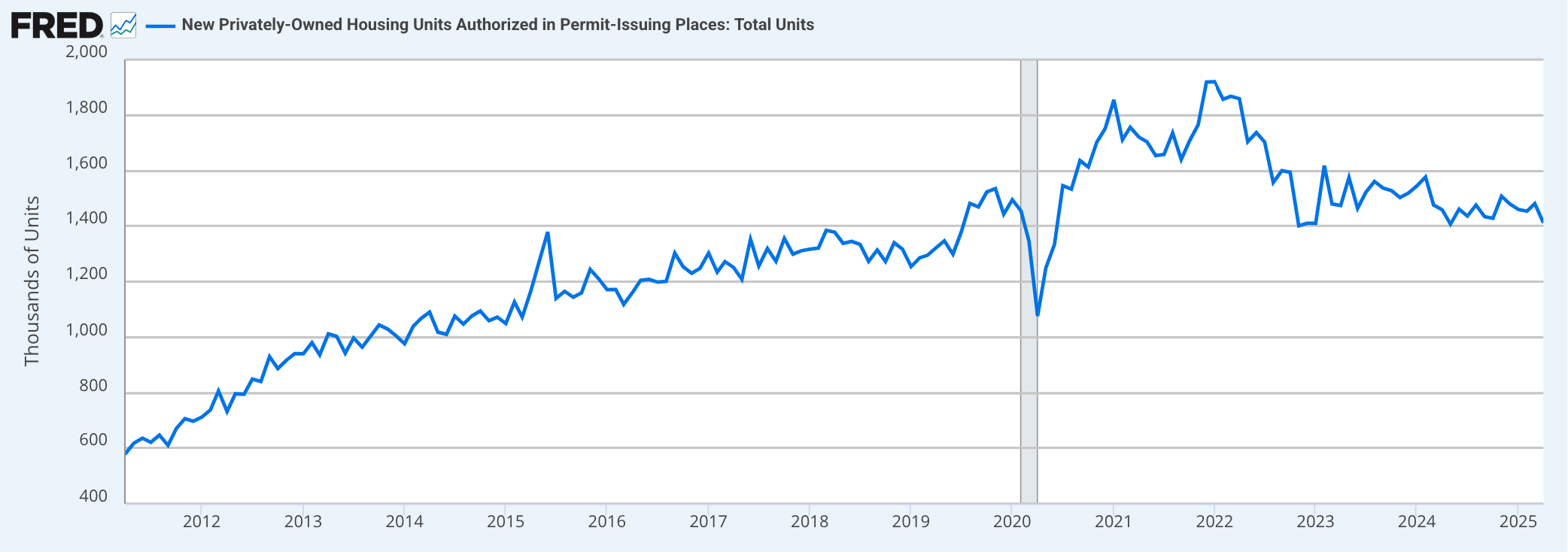

We only have to look to the housing market to see how these counterintuitive mechanisms may gain potency. While it is well-understood that higher mortgage rates curb the demand to purchase a home, they are also a signal to homebuilders to pull back. As of April 2025, the number of new residential units permitted is now back near its post-pandemic lows.

Two thirds of new residential units permitted are for single family units that primarily serve current and prospective homeowners, but another one third are for multifamily units, which primarily serve current and prospective tenants

The flow of new rental supply is slowing even as demand has held up well alongside a still-intact labor market. The supply-side inflation risk stemming from high financing costs and diminished homebuilding could therefore accelerate market rent inflation in the next 12 months. If such a risk materializes, the Fed's ability to achieve 2% inflation will be made more difficult. How the Fed reacts to such a risk will become pivotal.

Market Rent Acceleration - The Clock Is Ticking

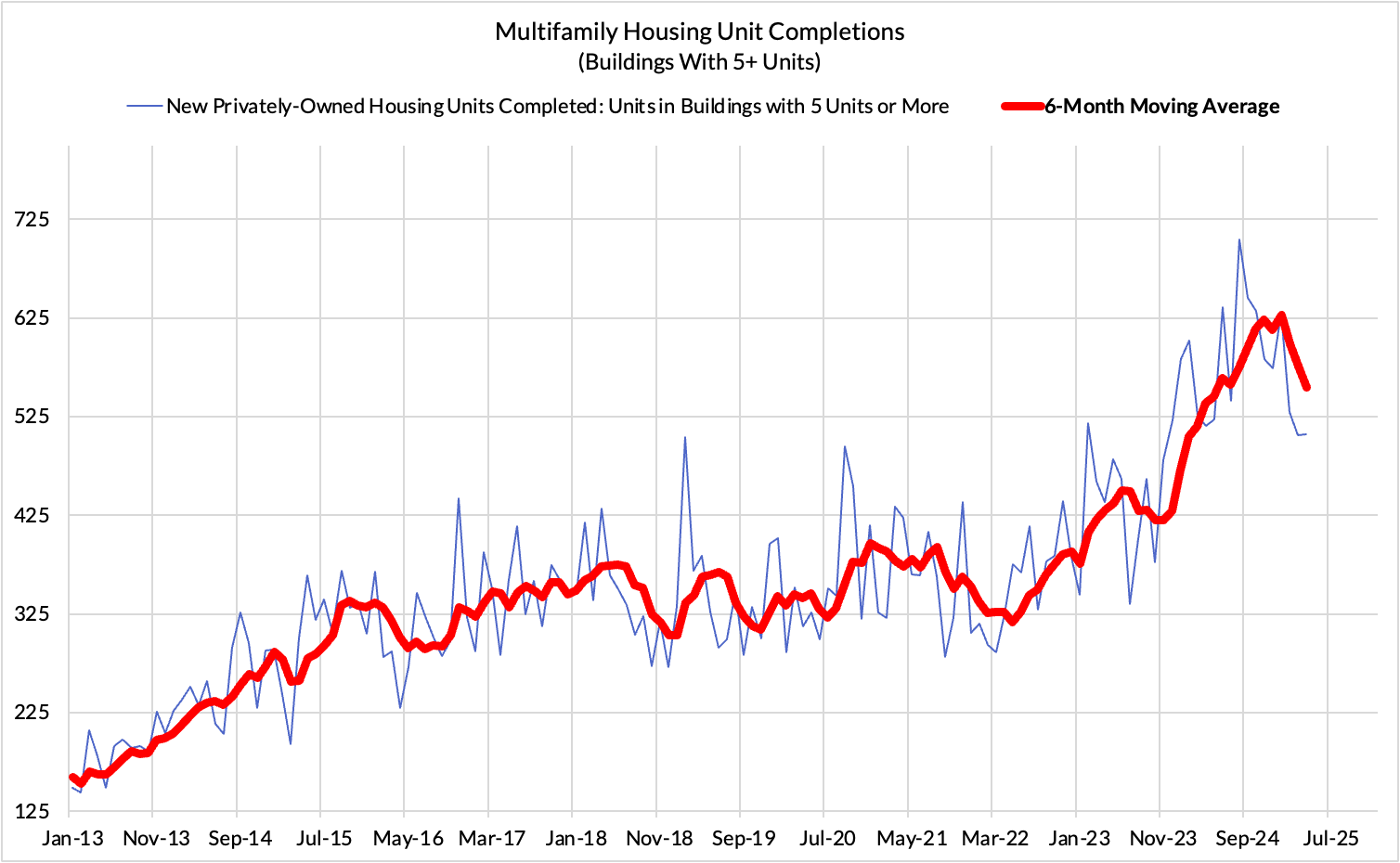

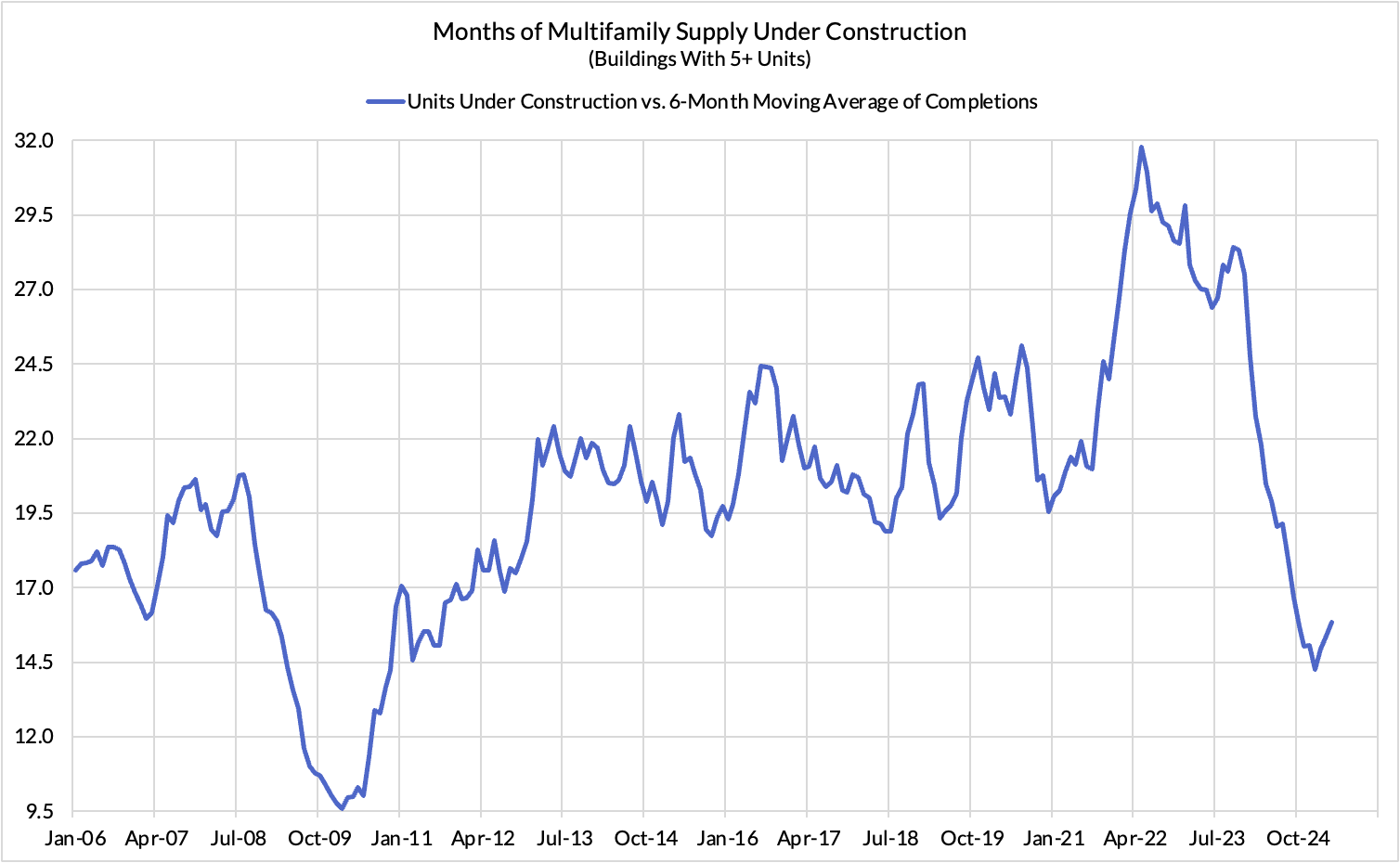

The housing market is sending a clear signal. Completions of multifamily housing units remain high, reflecting projects started in 2021 and 2022 when development financing costs for developers were still relatively low.

But the pipeline is drying up and so too the rate of completions now. The number of multifamily units under construction, which are predominantly occupied by tenants (renters), has continued to fall. The timeline for current multifamily unit backlogs to clear is now under 16 months, in contrast to the 22-24 month backlogs that prevailed just prior to the pandemic.

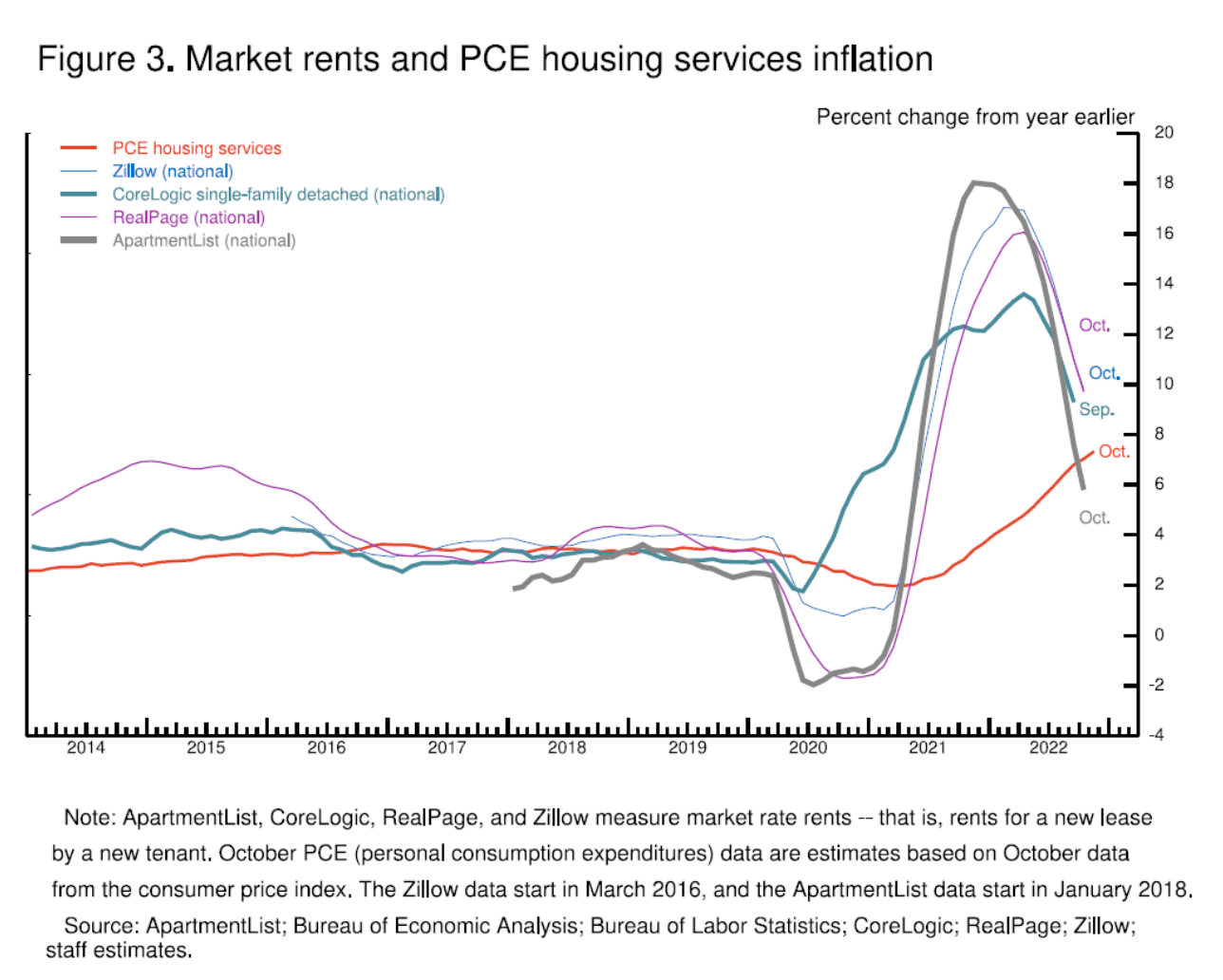

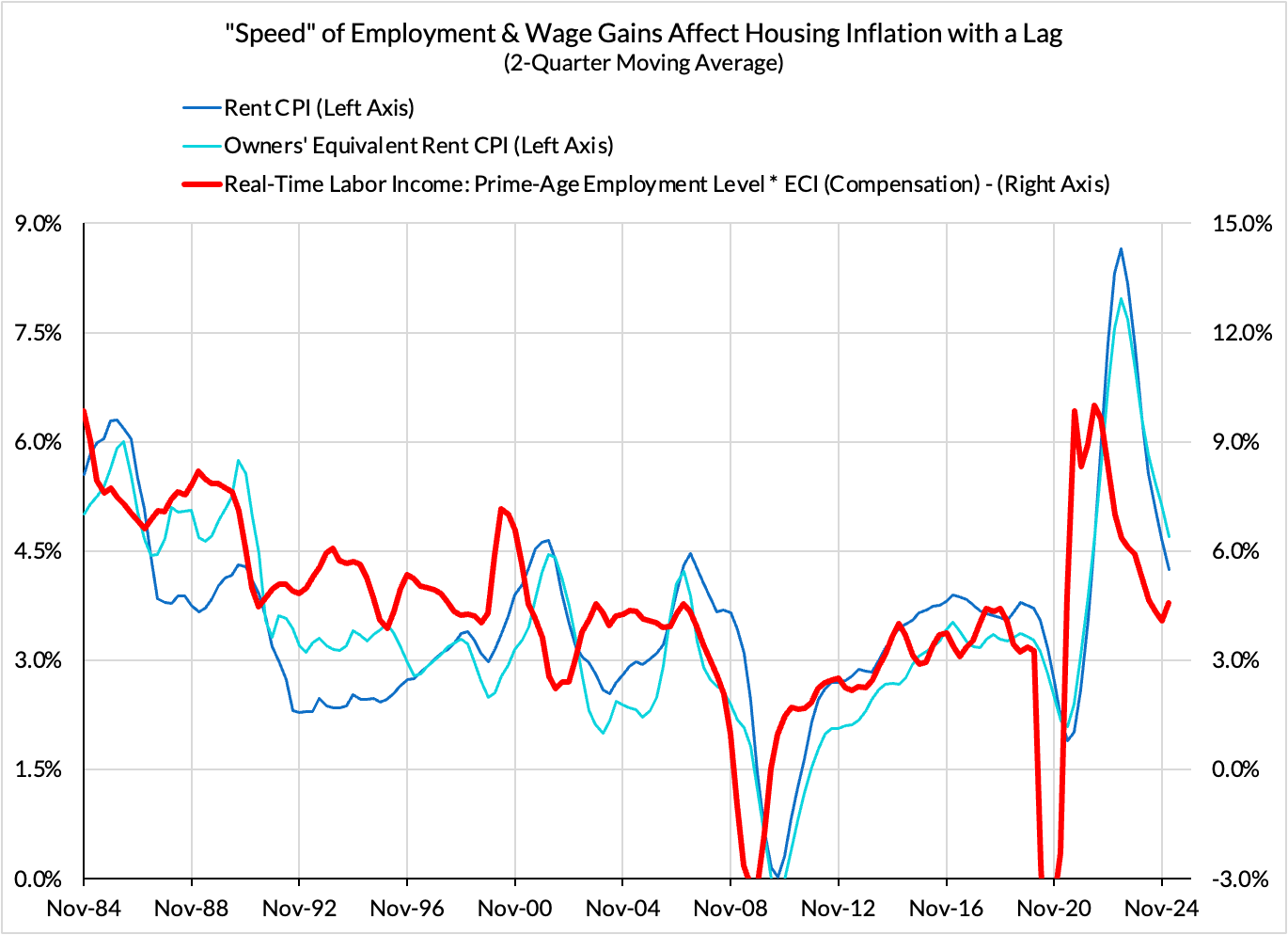

This matters because housing rent is a key driver of core inflation (18% of Core PCE). The Fed now appreciates that there are long lags between market rent dynamics and rent and owners’ equivalent rent (OER) CPI, and thus market rent inflation is worth special attention even if the housing components of CPI and PCE look more benign.

If we see a renewed pickup in market rent inflation, will the Fed be spooked into pursuing the very same policies that predominantly caused new rental construction to dry up in the first place?

Make no mistake, there are other sources of supply-side impediments in the housing market that help explain the structural housing shortage that has emerged over decades. State, local, and federal regulations are a longstanding constraint on homebuilding in a wide array of geographies, but it is also not a proximate explanation for the more recent erosion of new residential construction. Likewise, tariffs on building materials further increase the costs to developing more supply and will be a further headwind. Raising tariffs on building materials increase the threshold for developers to invest and build.

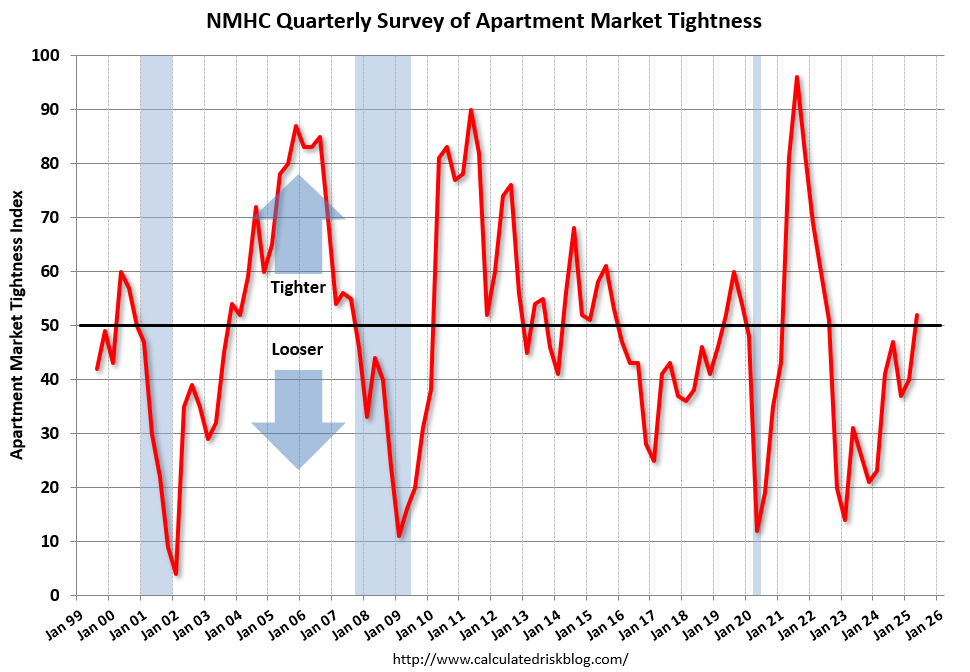

Prior to the threats and enactment of tariffs—a very recent phenomenon—signs of tightening in the rental housing market were swelling. The most recent release of the National Multifamily Housing Council's Quarterly Survey of Apartment Conditions suggests that apartment market tightness, a leading indicator of market rent inflation, is now increasing on balance (chart courtesy of Bill McBride at Calculated Risk). These readings were substantially driven by what transpired prior to the theatrics of Liberation Day.

As the current stock of under-construction buildings is completed and insufficient supply emerges to replace it, rental markets are liable to further tightening. If nominal household incomes merely avoid underperformance, steady demand growth for housing will persist. And in an environment where new supply is eroding, we could see market rents meaningfully accelerate in the next 12 months. That might not filter into CPI and PCE instantaneously, but it would with a lag.

Even if rent and OER CPI inflation are still slowing due to lags, consistent Fed policy will warrant acknowledgment of when forward looking data is shifting, even when less favorable. But if market rent inflation is substantially caused by restrictive financing conditions of the past few years, is the solution to restrict monetary policy further? The culprit in this instance wouldn’t really be overheating demand — it would be a policy-induced supply constraint.

The Interaction Between Supply and Financing Conditions

Tight financing conditions can have asymmetric effects. The Fed's interest rate hikes are meant to cool demand, but in terms of what matters for rents (how housing price inflation measures), the effects on supply (homebuilding) may be locally stronger than they are on demand (best proxied by the labor market).

Developers and builders pull back as financing becomes more expensive and expected profit margins shrink. Yet the demand for shelter rarely disappears in the absence of labor market fallout.

The Fed rightly frames inflation as a balance between demand and supply. But if housing inflation remains the dominant cyclical inflation constraint, as has been the case for some time now, the Fed's calculus has to recognize the supply-side effects of its own policies. Homebuilding activity is highly sensitive to interest rates, and as a result, Fed policy tightening may have a more adverse effect on the supply-side of the rental market than the demand-side. Homeowners typically borrow to fund their housing demand, but renters typically do not. While the Fed can tamp down quite directly on home price appreciation, its effects on rent inflation tend to run through other channels first. The very policy intended to tame rent inflation might inadvertently lay the groundwork for more of it.

Energy and Industrial Investment Can Exhibit Similar Dynamics To Housing

The same risks apply anywhere that finds cost of capital to be a binding constraint to new investment. Building out new capacity — whether in natural gas, transmission infrastructure, or renewables — can be finance-intensive, and in some cases, more directly sensitive to the level of borrowing costs. When financing costs rise, projects can be delayed or canceled, or else the pricing of the final products must reflect the additional cost.

While the market rent inflation risks reflect a risk to PCE inflation over the next 1-2 years, electricity price inflation dynamics are arguably more present. Electricity price inflation is now up 3.6% year over year and is set to rise further this year. Power demand is likely to increase as a result of rising LNG export capacity, electrification efforts, and energy-hungry data centers for the AI boom. Monetary policy's ability to curb power demand is likely to be limited, at least in the near term. Unfortunately, supply-side impediments remain, both longstanding ones as well as the mroe recent rise in financing costs. There is good evidence that financing costs are relevant to adding capacity and efficiencies with respect to electricity generation, especially as their build-out relies on leverage and project finance.

With power and natural gas prices already on the rise, the Fed has to think carefully about how its policies affect key prices. If investment slows while demand accelerates, energy prices can rise further, and with more volatility. Tight monetary policy may restrict the very investments needed to keep inflation stable and less volatile over the longer run.

Drechsler, Schnabl, and Savov show how credit crunches in the 1970s didn’t just hurt credit demand, but also credit supply, and that too in a manner that likely aggravated inflationary pressures. Manufacturing subsectors that were more dependent on external financing found it more difficult to invest and scale up inventory, thereby leading to less output, more unfilled orders, and higher prices.

Given the scale of policy change and uncertainty currently with us, we may be in the midst of substantial shocks and dislocations to the manufacturing sector. These firms are also dealing with an elevated cost of capital and even higher hurdle rates now. The full cost of adjustment is still to be determined. To the extent that higher financing costs weigh on the ability of the economy to adjust to shocks and supply dislocations, that may need to be incorporated into the cost-benefit analysis when evaluating monetary policy amidst supply shocks.

The Fed’s Dilemma

If the Fed interprets future inflation as new signs of overheating, it may tighten policy further — even though prior tightening may be partially to blame for setting these dynamics in motion. If the answer to inflation is always higher interest rates, regardless of the source, we risk chasing our own tail.

The post-pandemic economy has already shown how fragile supply chains, underinvestment, and sector-specific capacity constraints can drive up prices in ways workhorse macroeconomic models aren't built for. A microchip shortage that began in late 2020 ended up having some meaningful relevance to auto insurance inflation 3-4 years later, largely as a result of bottlenecking automobile production and raising prices for motor vehicles. To the extent that finance-dependent and interest rate sensitive sectors drive sharp relative price shocks in the coming years, the Fed will need a more robust strategy for navigating these tricky causal forces.

Conclusion: A Framework That Can Adapt To Supply Risks In Rate-Sensitive Sectors

None of what’s discussed here requires claiming "up is down" or "down is up." The Fed’s policies still operate, to a first approximation, along the directions that monetary policy tradeoffs are typically cast. Take interest rates high enough and you can cause a deep, disinflationary recession. Nevertheless, the structure of the US economy is heterogeneous and constantly changing, and so too are the transmission mechanisms by which the Fed affects the economy.

As a first step, the Fed could use nominal aggregates as a formal guidance tool for achieving the 2% PCE inflation target amidst uncertain supply disturbances. Nominal aggregates help separate out persistent and demand-side inflationary pressures, which monetary policy might be better suited to address, from the more idiosyncratic supply-side dynamics and relative price shocks that still affect the aggregate price level. Doing so would avoid overreacting to short-run inflation at the expense of longer run real output and employment performance.

As a more direct remedy to the role of financing costs and monetary conditions on the supply-side, the Fed should focus on nominal aggregates that exclude fixed investment spending. The segment of nominal income and spending that matters to the inflation target is at the household level, not the business level. The growth of paychecks and consumer spending better captures the causal nexus that underlies persistent consumer price inflation. There are multiple metrics of nominal labor income and consumer spending growth that would serve the Fed well when assessing and communicating about the persistent inflation risk that the Fed seeks to address.

It’s important for the Fed to update both its thinking and messaging when using monetary policy to address problems in the real economy. That includes recognizing when investment slowdowns are setting up future inflation risks and appropriately accounting for these dynamics in monetary policy decisions. These considerations are unlikely to predominate over any given monetary policy decision, but a forward-looking Fed would be wise to take note of how the last few years are poised to shape the next few. The Fed’s commitment to stable prices must ultimately span the short, medium, and longer run.