Revisions to macroeconomic data happen. Frequently. To almost all major releases, not just nonfarm payroll employment. Sometimes those revisions are large, and they are often largest at critical inflection points in the business cycle. Some of the largest revisions to employment and GDP transpired around the 2007-09 Great Recession, where both were underestimated in real-time and spawned bigger policy miscalibrations. For more context on revisions and how they can lead to flawed, overconfident claims on "Jobs Day," check out our piece from two years ago: Revision Whiplash: Why Coverage of Nonfarm Payroll Growth Is Messy, And How To Track Underlying Growth Better.

The monthly release of macroeconomic data is valuable to businesses, investors, and policymakers, all of whom can make better informed decisions, and plan and adapt with greater agility. That revisions increase the fragility and instability of news headlines is not a reason to complain about statistical estimation, to delay the release of data, or—worst of all—to influence statistical agencies politically. It is a reason to improve the presentation and reporting of what these rich, world-class datasets and data releases have to offer.

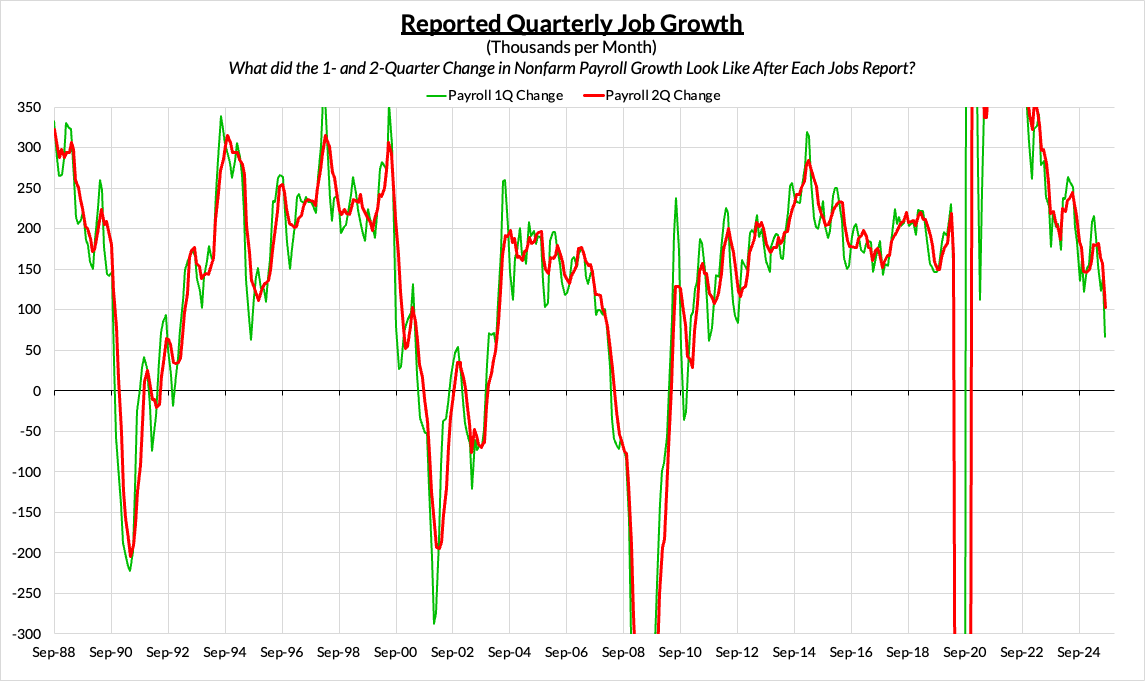

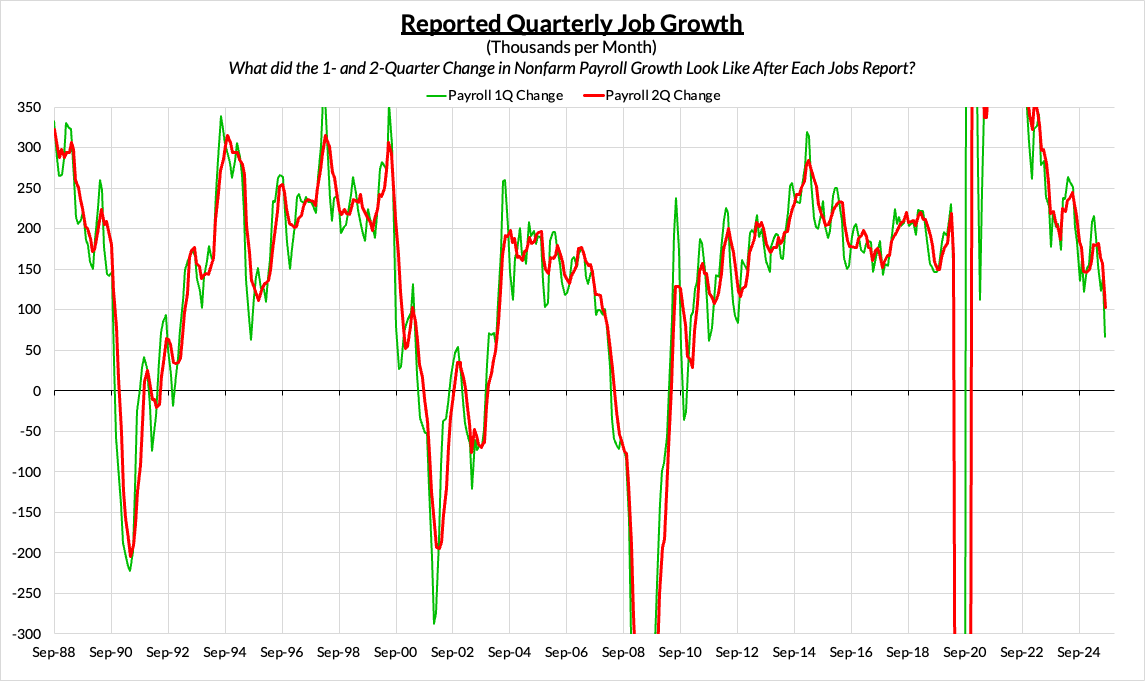

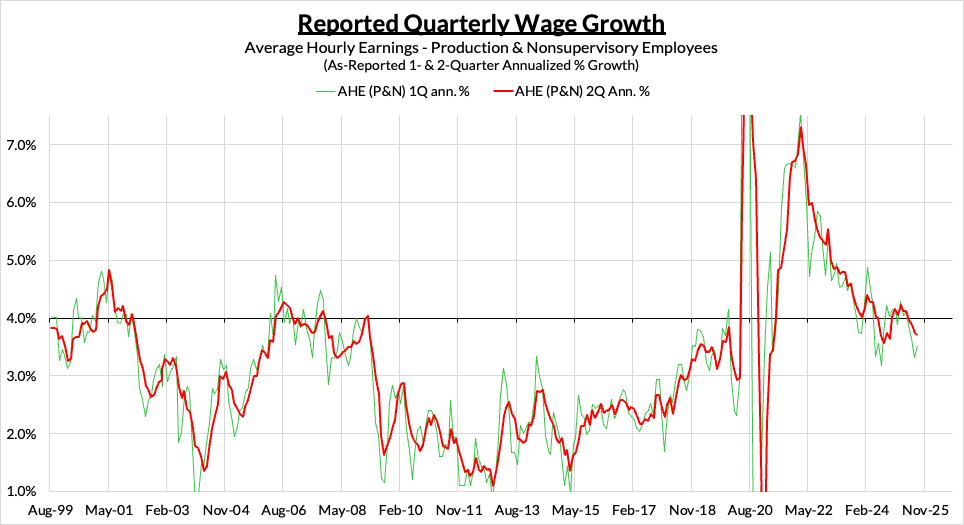

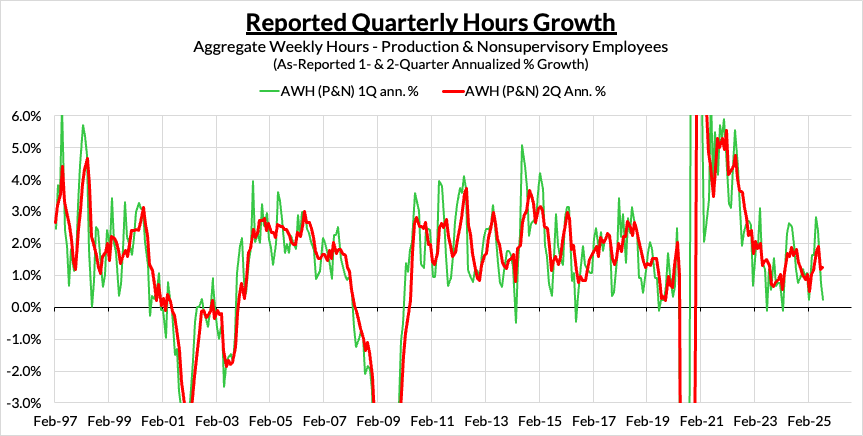

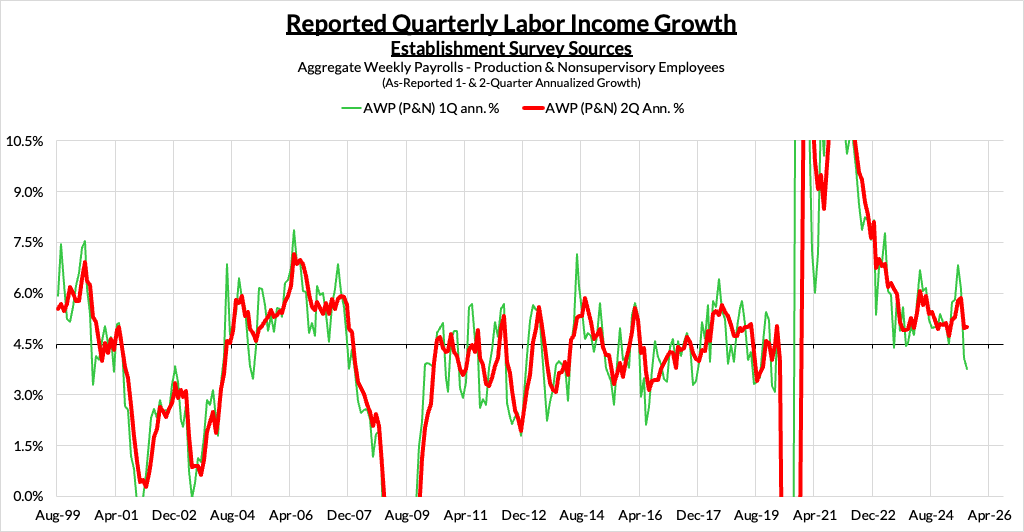

We would advise major media establishments to supplement their existing commentary with a "Reported Quarterly Growth" standard, especially when quoting changes in employment, wages, aggregate weekly payrolls, and aggregate hours worked. This means comparing the observed 1-, 2-, or 4-quarter growth rates in key indicators from the most recent Employment Situation "Jobs Report" versus what was observed in the prior report.

What Jobs Day Reporting and Communication Should Aim For

For both informed and less informed audiences, good reporting on indicators should:

- Summarize with simplicity all of the new information relative to the prior data release, with emphasis on the informational changes with greatest stability over time; and

- Stay historically consistent, both in the process for citing data and in the substance of economic commentary. Economies do not typically bounce month-to-month between recession and boom.

With these principles in mind, we encourage media establishments to regularly publish what we call a "Reported Quarterly Growth" standard for key Establishment Survey measures, like Nonfarm Payroll Employment (jobs) and Average Hourly Earnings (wages). Reported Quarterly Growth involves tracking how the latest 3-month average of data, on a 1-, 2-, or 4-quarter historical comparison, evolves from the previous Jobs Report ("The Employment Situation") to the most recent Jobs Report.

The Wisdom Of 3-Month Averages

Quarterly growth is typically measured by taking a 3-month average and comparing it to prior 3-month periods. The 3.0% 2025 Q2 Real GDP growth estimate is a comparison of the average level of real GDP in April, May, and June 2025 relative to the average across January, February, and March 2025. Because the levels of all macroeconomic data (GDP, employment, wages) are autocorrelated, the first monthly change in a given quarter will tend to have the highest impact on the quarterly growth rate.

For most monthly US macroeconomic data and certainly for the Establishment Survey, quarterly growth rates have an added benefit: the "final" revisions to the data only come two months after their initial release. By comparing 3-month averages to prior periods, the monthly change from two months ago will get more weight than the change one month ago, which is still subject to one more revision, and much more weight than the most recently reported monthly change, which has the greatest scope for revision.

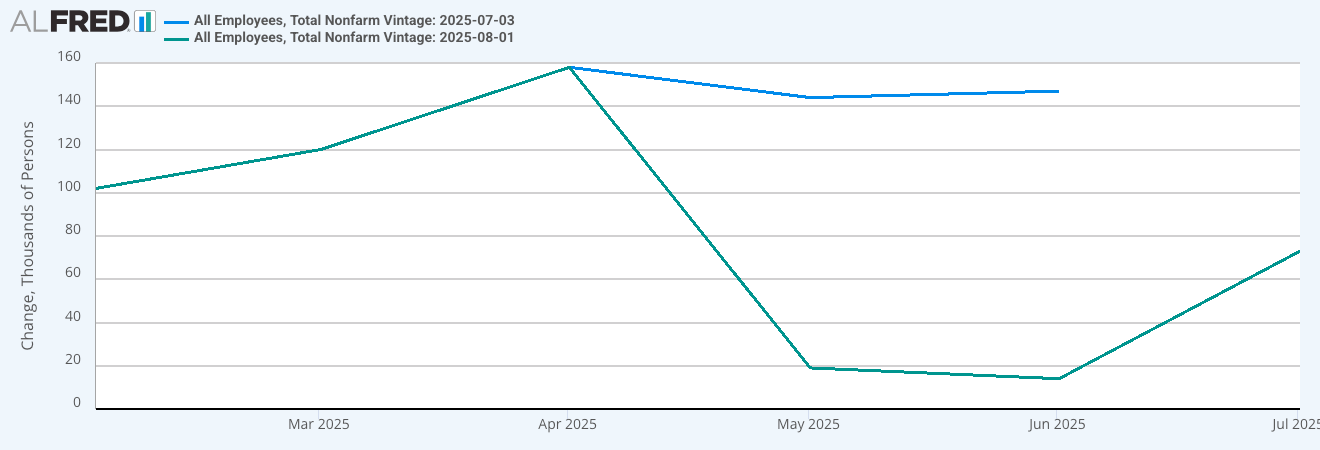

What Do We See In The Data Now Relative To What We Saw A Month Ago?

Critical to this exercise is to track how these quarterly growth rates, whether done on a 1-, 2-, or 4-quarter comparative lookback, evolve from data release to data release. We are not just gaining new information about one single month of data - we are gaining new information for at least three months of data. Updates to the prior two months of data must also be captured in a summary description of "what we learned in the most recent report relative to what we saw in the prior report?" The effect of revisions cannot be tackled unless we are carefully monitoring how "Reported" numbers are evolving over time.

Why focus on the growth rate instead of the level of key indicators?

The recent revisions to the nonfarm payroll data seem large at 258,000 across the last two months, yet pale in comparison to the 159.5 million total jobs estimated across the nonfarm business sector. A 0.16% error would be meaningless if we only cared about the level. But most users of timely monthly employment datasets do not primarily use them for counting the level of employment. The cited levels of employment are still updated later as part of "benchmark" revisions that factor in additional information, including changing rates of business formation and closure.

These indicators are built to tell us about the growth trajectory and momentum in the economy. Employment rarely goes down while investment and consumer spending are booming, and vice versa. With such a sectorally rich dataset, we can better understand the composition of growth and recession risk at a granular industry level, beyond big-picture unemployment level calculations. One-time changes in the estimated level of a data series can cause a permanent "drift" that makes robust estimations of levels much more difficult than estimations of growth rates and broader business cycle dynamics.

The Call For Improved Reporting Is Not Intended To Absolve Behavior That Undermines Trust In The BLS

Our suggestions here are for improving public understanding of rich but complicated datasets. They are not meant to cast doubt on the datasets or the people involved in data collection and statistical estimation; the intention is precisely the opposite. The data's strengths deserve better presentation, and even though the preliminary data can be volatile, its timeliness is valuable if handled responsibly and weighted accordingly. The media does the BLS few favors when gravitating to the employment reading that is the most vulnerable to large future revision; specifically the most recent month's change in nonfarm payrolls.

Our suggestions should also not serve as an excuse for willful ignorance, or engaging in deceptive or misleading claims. We see no demonstrated incompetence from the BLS in how they revise estimates as a result of more information and data collection. Accusations that the data are phony and rigged—merely because of large downside revisions to employment—lack credibility. Trust is difficult to achieve and easy to throw away.

We nevertheless hope that media establishments see the merit of supplementing their reporting of the Establishment Survey with Reported Quarterly Growth measures. It can offer a clearer understanding of how the known set of information is changing with each passing month. The public is less likely to be frustrated trying to reference a headline they heard on the news just one month ago, only to be unable to subsequently find it. Datapoints with greater stability would ideally carry greater headline status, but at the very least, they warrant some supplementary emphasis.

American macroeconomic data releases server important functions that extend beyond public understanding and civic education. But if they are to survive and thrive in the years ahead, institutions and communicators of all kinds would benefit from rigorous, standardized approaches to understanding and reporting on these data to enhance public understanding and reinforce data legitimacy.

To see what these measures look like in practice, please stay tuned. We will publish a walk-through demonstrating how Reported Quarterly Growth rates can supplement a more robust understanding of what the July jobs report told us about the labor market and key sector-level trends.