By Skanda Amarnath

Whether you’ve been converted to #FloorGLI or you stick to the Fed’s preferred methods for framing economic developments, the case for the Fed to cut 50 basis points at the June FOMC meeting is underrated. With the caveat that new economic, financial market, and political developments can always change the outlook, we do hope that the Fed recognizes the urgency of the current moment.

The Fed viewed financial conditions at its March and May meetings as appropriate to achieve its mandated objectives. Since then we have learned:

- Financial conditions have tightened, even as there has been growing anticipation of Fed easing.

- The labor market has decelerated further, while the inflation outlook remains tame.

- The underlying drivers of aggregate demand remain weak.

- Risk management around the lower bound constraint suggests erring on the side of easing earlier and faster.

0. The Fed viewed financial conditions at its March and May meetings as appropriate to achieve its objectives.

- The March SEP showed that the FOMC was of the view that optimal policy would involve no changes to the fed funds rate, but that the tight labor market might suggest a hike later in 2020.

- In May the FOMC emphasized the need for continued patience, in keeping with its March projections for no changes to the federal funds rate in 2019.

- But the notion that “patience” amounts to a hard commitment not to raise or cut rates at its June and/or July meeting is off-the-mark. The Fed, like any good risk manager, prefers optionality, especially if it comes at limited cost. It wants to be careful about when it makes a policy commitment. What we’ve seen in recent statements from Chair Powell, Vice Chair Clarida, Governor Brainard, and President Evans all suggest that the Fed is keeping an open mind ahead of the June FOMC meeting. President Bullard has more forcefully recognized that the environment may now require an imminent policy response.

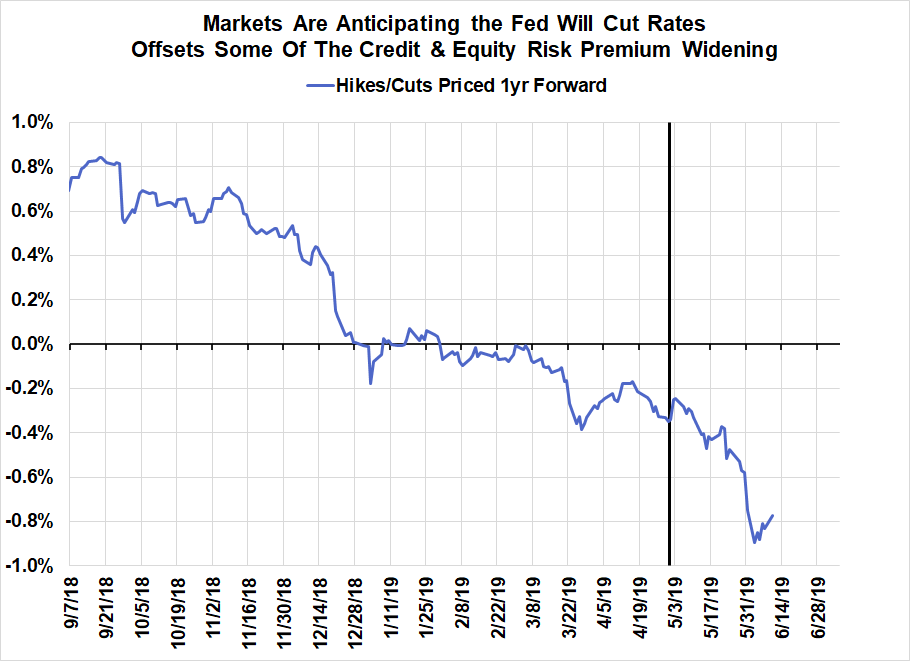

- Financial markets suggest a different policy path will be needed to achieve the dual mandate even if the outlook remains unchanged from the May meeting. Despite financial markets pricing in more easing from the Fed, financial conditions broadly appear to be less supportive of the growth outlook.

1. Financial conditions have tightened since the May meeting, in spite of greater anticipation of Fed easing

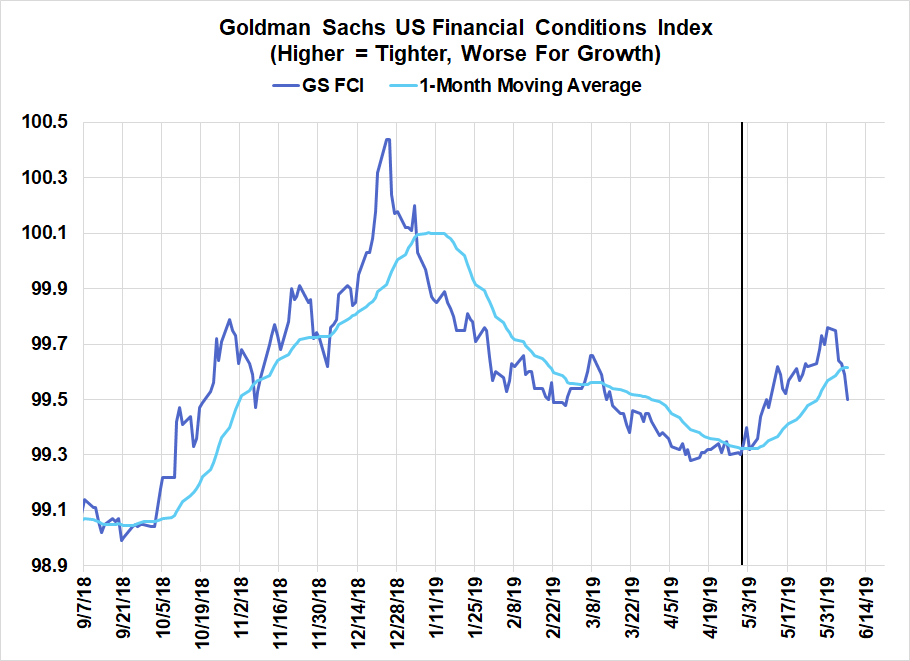

The Goldman Sachs (GS) U.S. Financial Conditions Index (FCI), which is calibrated using the Fed’s own FRB/US model, shows tighter conditions (weaker for growth) since the May 1st FOMC meeting.

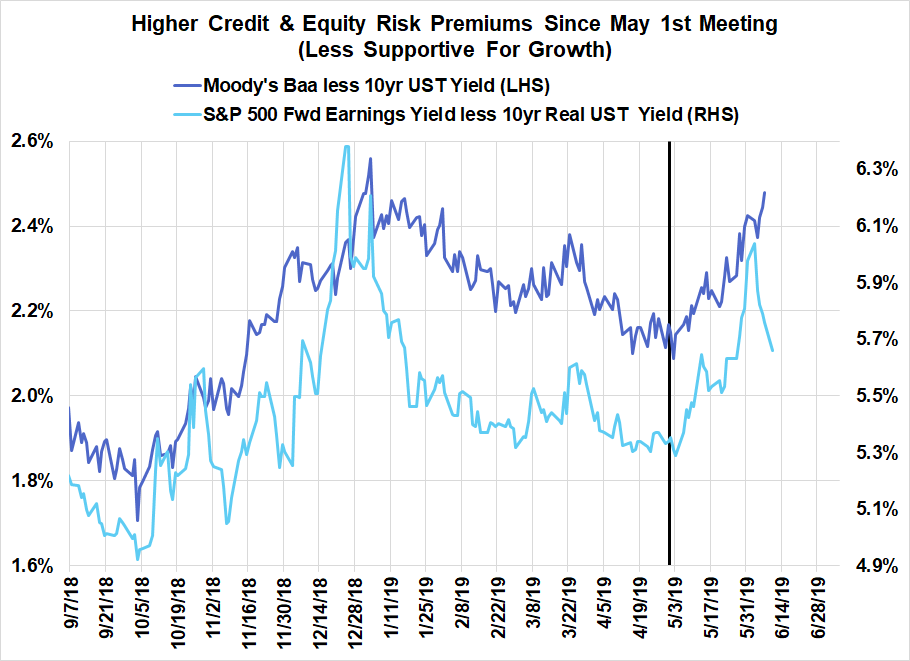

- The tightening primarily reflects higher credit and equity risk premiums. Weak global growth data and broadening trade war turmoil have been the key catalysts for weaker performance in “risk assets” like stocks and corporate bonds. Lower commodity prices are not reflected directly in the GS U.S. FCI but could potentially have an outsized effect on capital investment in the US because of the size and growth of our energy and agricultural sectors.

- Financial conditions would be meaningfully tighter today if financial markets were not pricing in so many rate cuts over the next six quarters. While the Fed implicitly contributed to Q4 market turmoil, market interpretation of the Fed’s reaction function has offered a very helpful offset in this episode of FCI tightening.

- If the Fed chooses not to deliver the market-implied Fed easing, it should expect financial conditions to tighten further, all else equal. Markets can misinterpret the Fed’s reaction function. If the Fed wanted to communicate that market pricing of future rate cuts was not justifiable, it should naturally expect tighter financial conditions and a weaker growth outlook as a result. Given the recent deceleration in economic trends, a further weakening in the growth outlook could prove especially risky.

2. The labor market is now clearly slowing, and the inflation outlook was already quite tame.

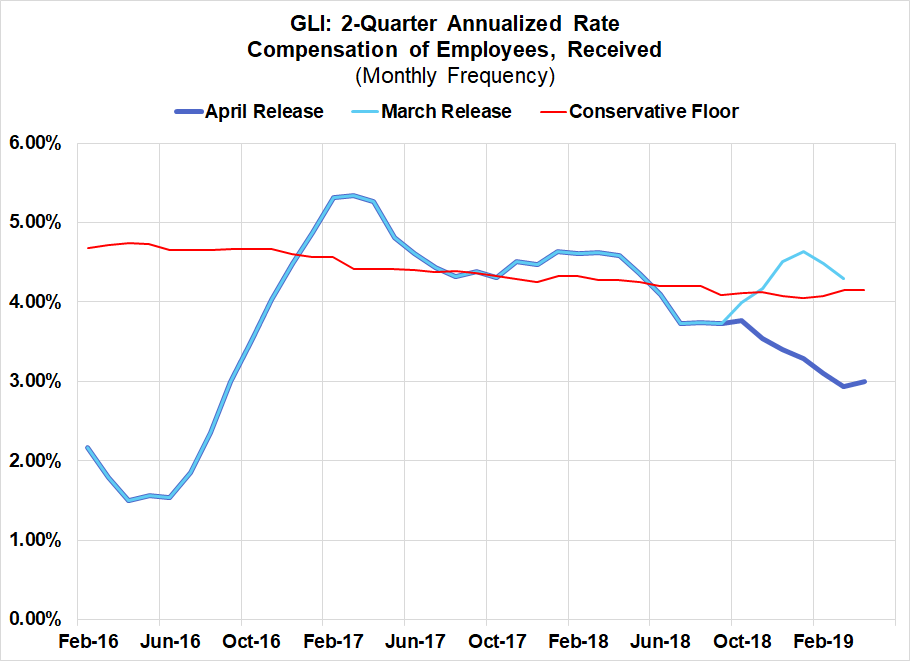

We’re fans of looking at gross labor income (GLI), the accumulation of each employed person’s compensation. What we’ve learned since the May FOMC meeting about GLI is worrisome. The deceleration in GLI is also likely to weigh on the spending outlook for households. At the same time, even if you buy Chair Powell’s view that the recent decline in core inflation is transitory, the inflation outlook is very tame and inflation readings generally tend to lag the cyclical environment.

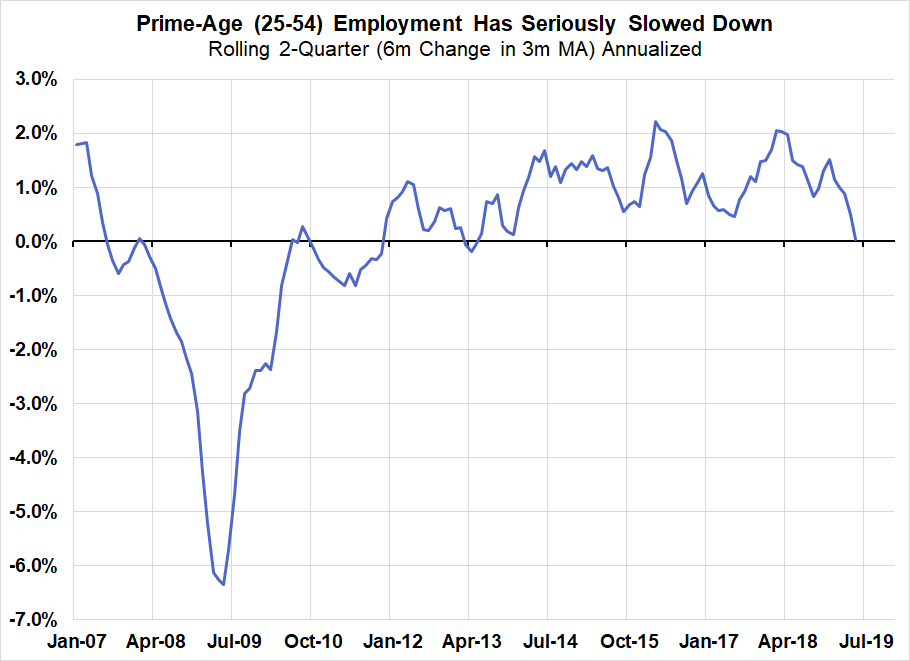

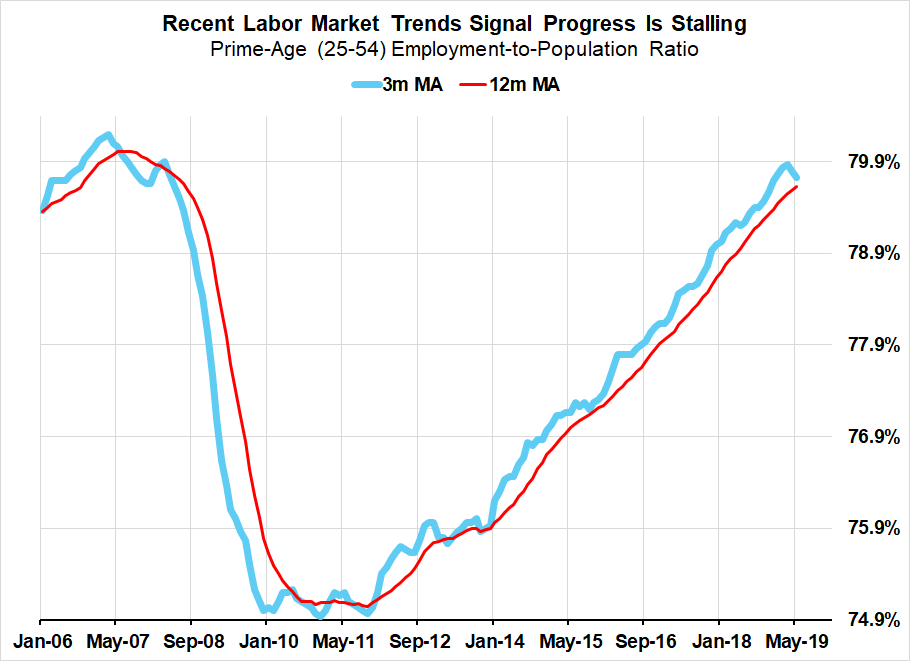

- Prime-age employment trends are signaling elevated slowdown and recession risk. The household survey (CPS) is more volatile than the establishment survey (CES) but is also a better real-time indicator, especially since there is no issue of revisions. What you see is what you get. What we got in April suggested that prime-age employment growth was slowing. The May report only confirmed that we’re now seeing near-contraction in employment for the key set of cohorts that drive labor supply and labor income growth.

- We learned at the end of May that GLI growth has actually been much slower over the previous 12 months. The “Compensation of Employees, Received” measure in the Personal Income release was previously pointing to a 4% growth rate, close to where we would conservatively set a floor under GLI growth. As of last Friday, year-over-year GLI growth fell sharply from 4.0% to 3.4% in the April release. This observed weakness is in large part a function of wage growth proving to be softer than previously estimated.

Weak inflation might prove transitory but persistent upside risks are difficult to identify.

- Despite claims that the labor market is too tight, the upside risks to wages and prices have largely failed to materialize. Real and nominal measures of labor market strength are now cooling.

- Headline and core PCE inflation readings remain below target.

- Market- and survey-based measures of inflation expectations also remain low.

- The Fed’s trade-weighted broad dollar index is historically strong

- Commodity prices have fallen.

- Tariffs have put upside risk on certain imported goods but countermeasures and weak global demand have also softened the prices of goods that are commonly exported, such as certain agricultural products.

3. The underlying drivers of aggregate demand also suggest downside risks to the outlook

- Households: With the labor market (jobs and compensation) slowing, the outlook for consumer spending also looks weaker over the coming quarters. Lower long-term interest rates might offer some offset via stronger housing activity.

- Businesses: The business fixed investment outlook seems to be weighed down by a combination of tighter financial conditions, uncertainty related to the trade war and global growth, and declining commodity prices.

- Foreign: Even before the trade war heated up, global growth was decelerating, as Chinese policymakers began restricting the growth of credit and pushing SOEs to aggressively deleverage. This dynamic, along with a historically strong dollar and Brexit-related uncertainty, have exposed major export-dependent and emerging market economies.

- Government: Despite historic federal government deficits, fiscal support for demand is waning. Most of the increased spending that Democrats and Republicans agreed to at the beginning of 2018 is now in the rearview mirror. The Federal government’s spending outlook remains uncertain and will only be clarified following upcoming negotiations later this year. While state and local government spending is providing a useful offset for the time being, its procyclical nature would suggest caution when extrapolating forward.

4. Risk management: the Fed can always hike, but it can’t always cut.

The Fed should err on the side of cutting earlier and faster so that it is not stuck in a position where it would like to cut but can’t.

- FOMC members acknowledge the basic reality that stems from a lower bound on policy rates. Sure, there are unconventional tools that the Fed will try to make more conventional. However, their effectiveness is uncertain. For a variety of reasons, LSAPs might very well be less effective in the next downturn.

- The Fed can always reverse easing if its outlook proves too pessimistic. Reversing cuts is not a cost-free exercise but given the nature of the Fed’s problems (e.g. low inflation, underestimation of maximum employment, low nominal growth, low interest rates), there is one side on which it should clearly err.

- Why a 50 basis point cut? Why not 25? Macroeconomic outcomes have obvious negative skew. Downside risks tend to occur with greater speed and intensity than upside risks, and upside risks have also become less frequent. Policy has grown more asymmetric in its response over recent business cycles, but has still failed to match the asymmetries of our macroeconomic realities.

Why as early as June? What is the cost of waiting?

- Bad stuff happens quickly (negative skew) and the Fed is in a strong position to prevent, rather than mitigate. If it eased in June by even 25bps, then as long as it did not offer especially hawkish guidance, the net effect would be easier financial conditions, which could help support better nominal growth outcomes and the dual mandate objectives.

- While there are political developments related to trade policy that might motivate the Fed to act with greater certainty in July after the G20 summit, the areas of weakness are no longer limited to the political sphere. Politics inevitably plays a role in shaping the economy, as it has more recently through trade policy, the government shutdown, and the diminishing effects from prior fiscal stimulus. However, the labor market data is already deteriorating at a fast enough pace that maximum employment is at risk. The case for the Fed to cut should not be a function of any individual political event.