September 2024 FOMC Preview

Our new baseline is a 50 bps cut with a total of 75 bps of cuts in the SEP for 2024. It’s a close call but we think a 50 bps cut is more likely than a 25 bps cut. We think a 50 bps point cut is the right move.

Our new baseline is a 50 bps cut with a total of 75 bps of cuts in the SEP for 2024. It’s a close call but we think a 50 bps cut is more likely than a 25 bps cut. We think a 50 bps point cut is the right move.

If you enjoy our content and would like to support our work, we make additional content available for our donors. If you’re interested in gaining access to our Premium Donor distribution, please feel free to reach out to us here for more information.

Quick takeaways. We dive more into the details below.

What we think will happen:

Our view on what should happen:

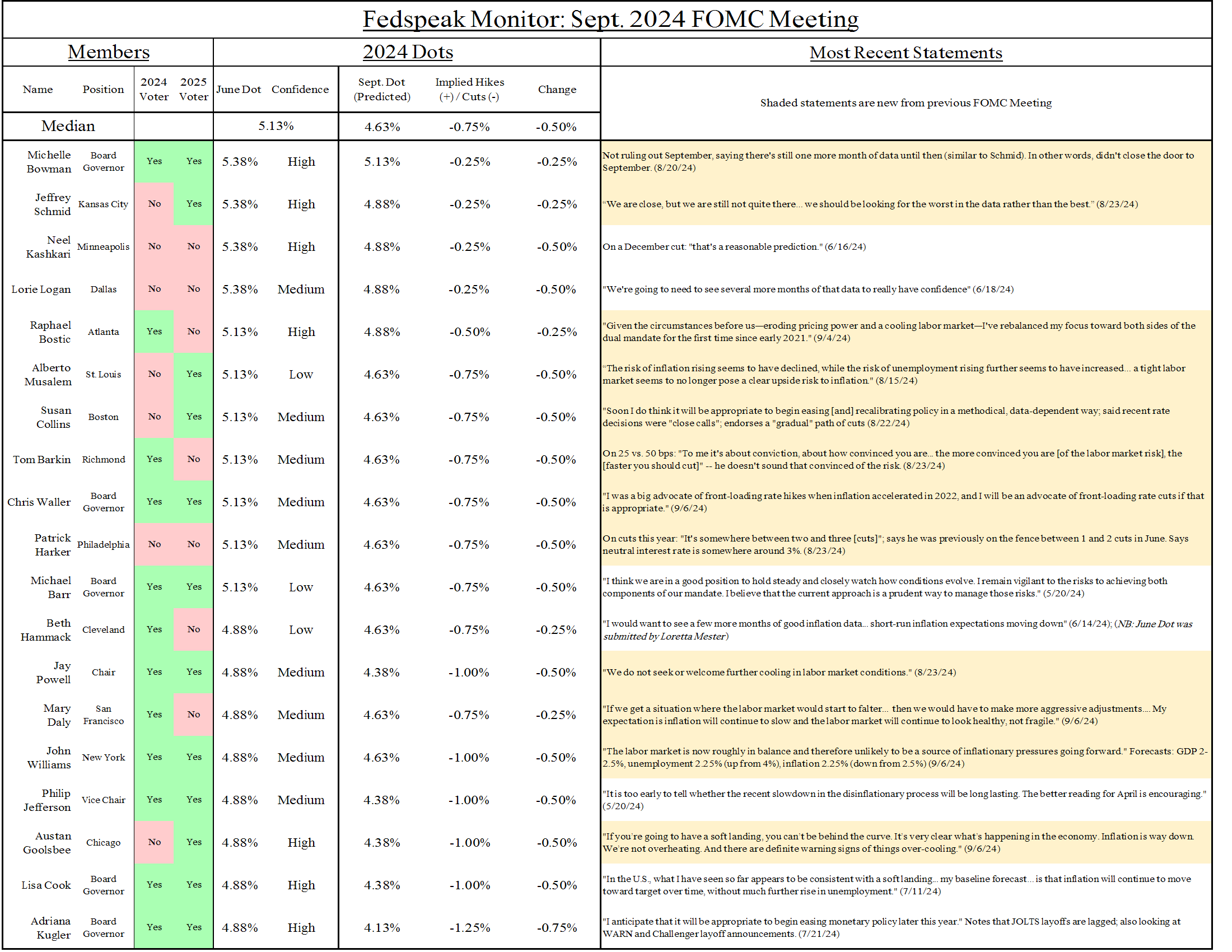

While the rest of the Committee doesn’t seem excited about a 50 bps cut, we think Powell can get it over the line. Despite the doves on the Committee not coming out in support of 50, the fact that they haven’t really dismissed the idea indicates that they’ll be on board with 50. The question is whether Powell can get members like Waller to go along with 50. While last week we would not have predicted 50, the recent calls from Republican lawmakers and a benign August inflation nowcast make it more likely that Powell will be able to convince the somewhat more hawkish members of the Committee to start with a 50 bps cut, as long as they don’t signal too many cuts for the rest of the year.

A "hawkish 50" is easier to navigate. They can always add in more cuts later this year if they think it’s warranted, and it would be harder to criticize them for being behind the curve given the initial 50 bps move; they can also delay the cut and still claim consistency with the more cautious pace signaled by only additional cut through the rest of 2025.

On the other hand, a “dovish 25” is at best very awkward. If they put forth 25 bps cuts in September and an additional 75 bps of cuts through the end of the year, it looks like a premature admission that they plan on being behind.

Between the hawkish and dovish scenario, the hawkish scenario (25 bps cut in September, 75 bps of cuts projected through the rest of the year) is the more likely scenario.

Whether they go for 25 bps or 50 bps, Powell will justify the move as simply recalibrating policy rather than a significant shift towards firefighting mode. They won’t want to confirm suspicions that they are (or were, in July) behind the curve in easing. Expect another statement that they don’t want to see the labor market weaken from here, but also that they’ll use the most recent labor market data to confirm that they’re on the right track.

Between the July and September meeting, the Fed will have seen two months of jobs and nearly two months of inflation data (enough from CPI and PPI to make an accurate prediction of PCE inflation in August). The inflation data for both July came in relatively benign, and the Fed was likely especially encouraged with a substantial fall in supercore inflation. Despite core CPI looking a bit warm in August, there were favorable prints in the financial services, health care, and airfare portions of the PPI, all of which feed directly into core PCE. As of Thursday (after PPI, before IPI), core PCE is on track to print 0.12% month-on-month in August. The good news progress in inflation has been especially pronounced in the key core serves ex-housing portion.

The big turn in Fed policy this meeting is that the Committee now claims to be equally concerned about labor market and inflation risk. The jump in unemployment in July to 4.3% and the triggering of the Sahm rule caught their attention. Although prime-age employment levels are healthy, the momentum of the labor market is clearly slowing even if it is not outright deteriorating. The trend from the past few months of data is clear: hiring has taken a big step backwards, despite low layoffs and job growth has slowed. The soft data from the Beige book suggests that many employers are looking to reduce headcount through attrition. Wage growth may be historically high in terms of nominal growth, but can be justified by the high productivity readings. The job openings number took a big step back in August and by that metric the labor market looks exactly “balanced.”

Meanwhile, the idea of a 50 bps cut has gained traction in recent days. A number of former Fed officials and prominent names in monetary policy have given the nod to a 50 bps cut. Despite Trump opposing the Fed beginning rate cuts before the election, several Republican lawmakers are now on the record as supporting cuts in September. This includes Thom Tillis (R-NC) and John Kennedy (R-LA), the latter of which went so far as to support a 50 bps cut.

The Fed should be cutting by 50 bps at the September meeting. The progress in inflation and the rise in unemployment should have been enough to justify beginning the process of normalization in July, and the subsequent labor market data has affirmed that. The labor market has more than rebalanced, with labor demand underperforming the growth in labor supply and wage growth running low relative to the inflation target and productivity growth.

More generally, we still believe that the path to normalization should feature front-loaded cuts. If the labor market is currently balanced but has been on a slowing trajectory, this speaks to elevated downside risks to the labor market that we do not see as outweigh nebulous upside risks to inflation from “international stability risks.” For months, the Fed has been trading timeliness for certainty; now that they have certainty, it’s time to play catch-up. Finally, uncertainty around the natural interest rate warrants a gradual path of rate cuts—at the end, when we approach neutral, not at the outset.

Instead, the Fed seems to have boxed themselves into a path of gradual rate cuts based not on the data but on institutional inertia and a desire to not spook the markets. This could backfire if it turns out that the Fed has waited too long and has to cut faster later. Instead, the Fed should back up Powell’s commitment to preventing further loosening of the labor market—they can do that by starting with a larger cut.

Here is a quick summary of our recent stances on how the Fed should approach cutting:

Prior to the labor market data for August, we preregistered our thoughts on what should justify a 50 bps cut at the September meeting: an unemployment rate of at least 4.2% and/or a decline in the prime-age employment rate. With the unemployment rate in august coming in at 4.2%, we feel that 50 bps is the right call.