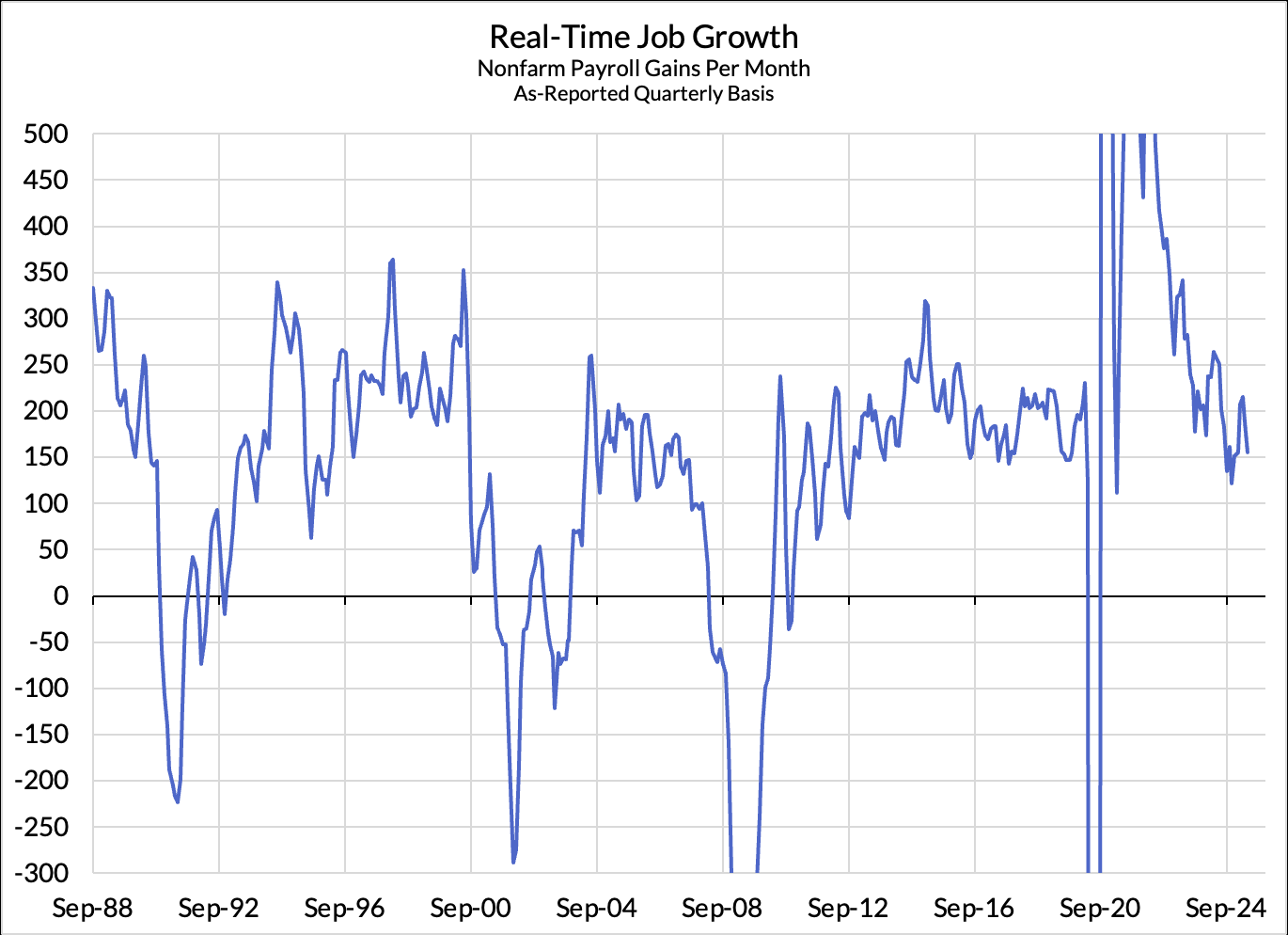

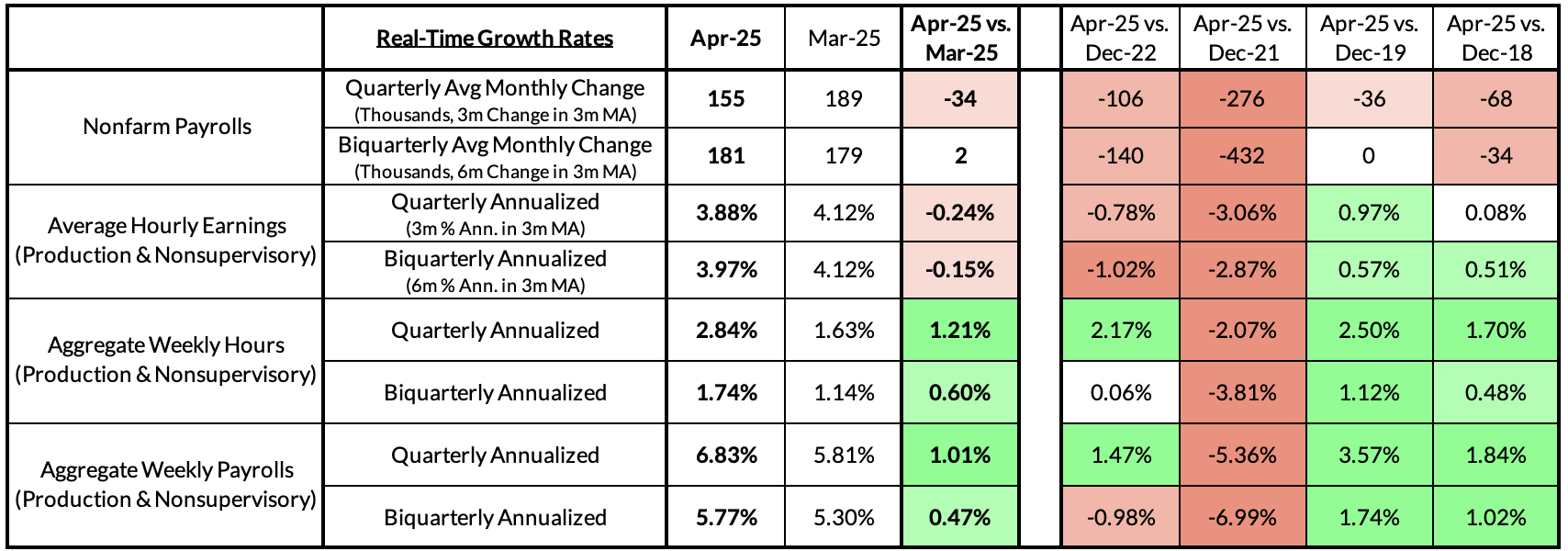

The labor market added 177,000 net jobs in April, with revisions of -15,000 and -58,000 to February and March, respectively. The payroll print was well above both consensus and our own forecast. The unemployment stayed at 4.2% and prime-age employment rose to 80.7%, down 0.5pp from six months ago but still 0.7pp above its 2019 average. Prime-age labor force participation rose 0.3pp to 83.6pp.

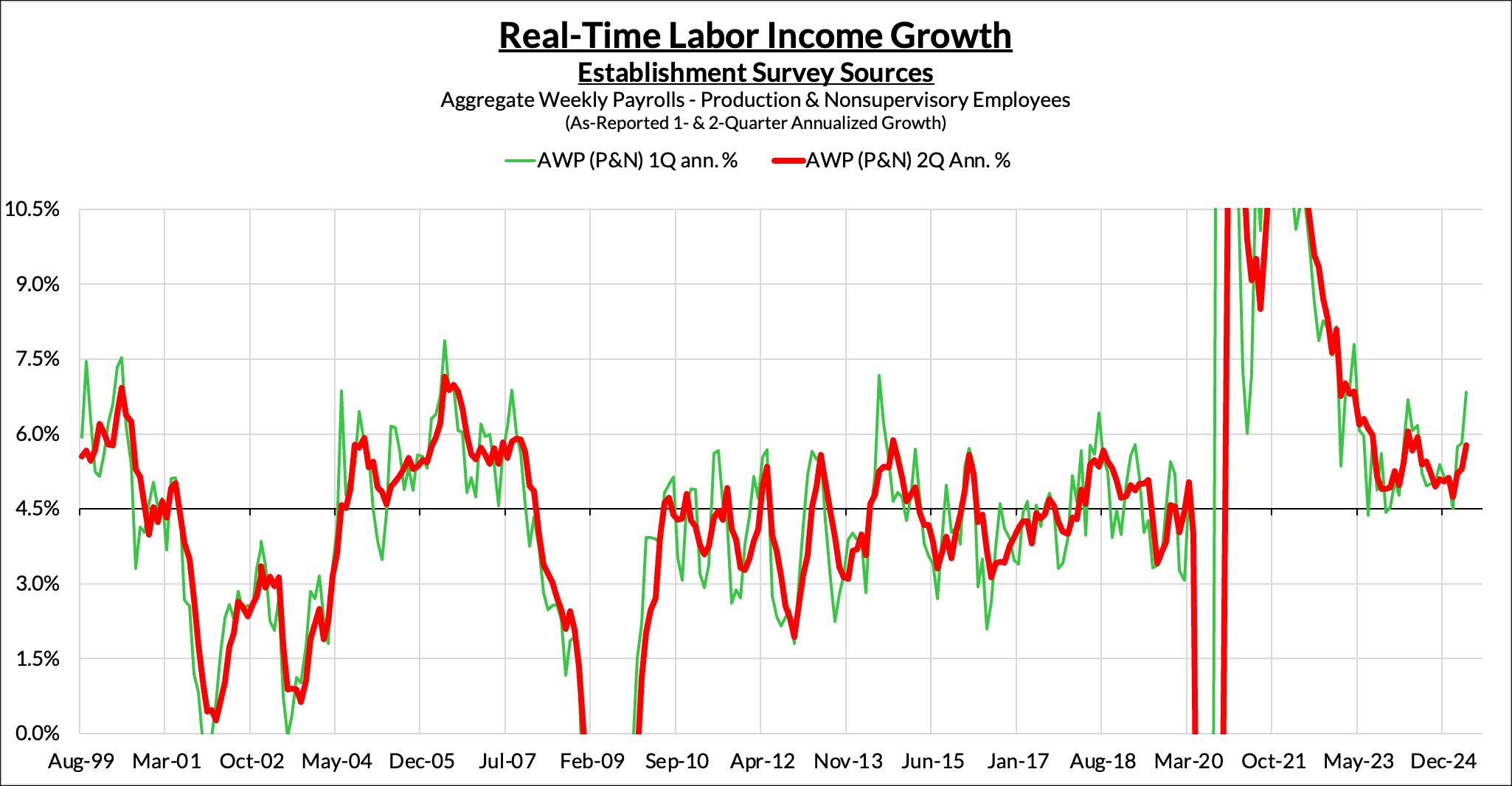

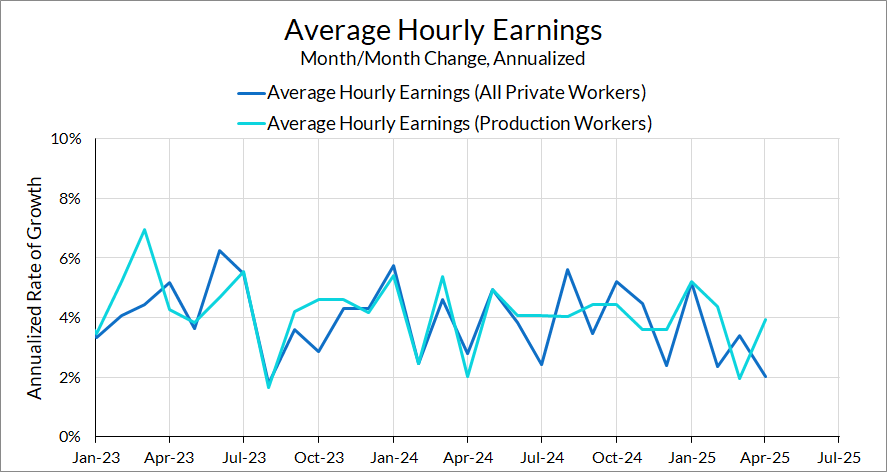

Average hourly earnings grew by a scant 2.0% (annualized) in April, bringing the year-on-year growth rate down to 3.76%. Wages in the Employment Cost Index grew at a 3.1% annualized growth rate during the first quarter, well within the range of pre-pandemic growth rates. In the JOLTS data, which cover March, hiring rates were flat, quit rates moved up slightly, layoffs moved down slightly, and job opening rates fell. Unemployment claims showed signs of distress among public administration and federal workers, but otherwise there was no sign of wider labor market distress.

This month’s jobs data comes a month after “Liberation Day” and everyone, us included, are looking for signs that the effects of tariff policy will show up in the labor market. If you were expecting it to show up this month, it’s too early (remember, the surveys cover the pay period of April 12th—a mere 10 days after the initial tariff announcement). So far, pain from the tariffs has not shown up in any obvious way in the labor market data, and it may not for a few months—currently, our recession call is for one to start in the third quarter if we see one. Right now, businesses are saying they’re on pause while tariff policy gets sorted out, and that may also apply to layoffs as well.

The Labor Market Data is Still Good

If you’re looking for evidence of the trade war slowing down the labor market, you didn’t get it in this report. The payroll print beat expectations, and the household survey showed gains across a broad range of metrics. Prime-age employment rates, our preferred gauge of the health of the labor market, showed a decent increase, from 80.4% to 80.7%.

That increase in employment rates was mostly driven by an increase in labor force participation. Prime-age labor force participation rates also rose 0.3pp, to 83.6%. The overall unemployment rate remained steady at 4.2%

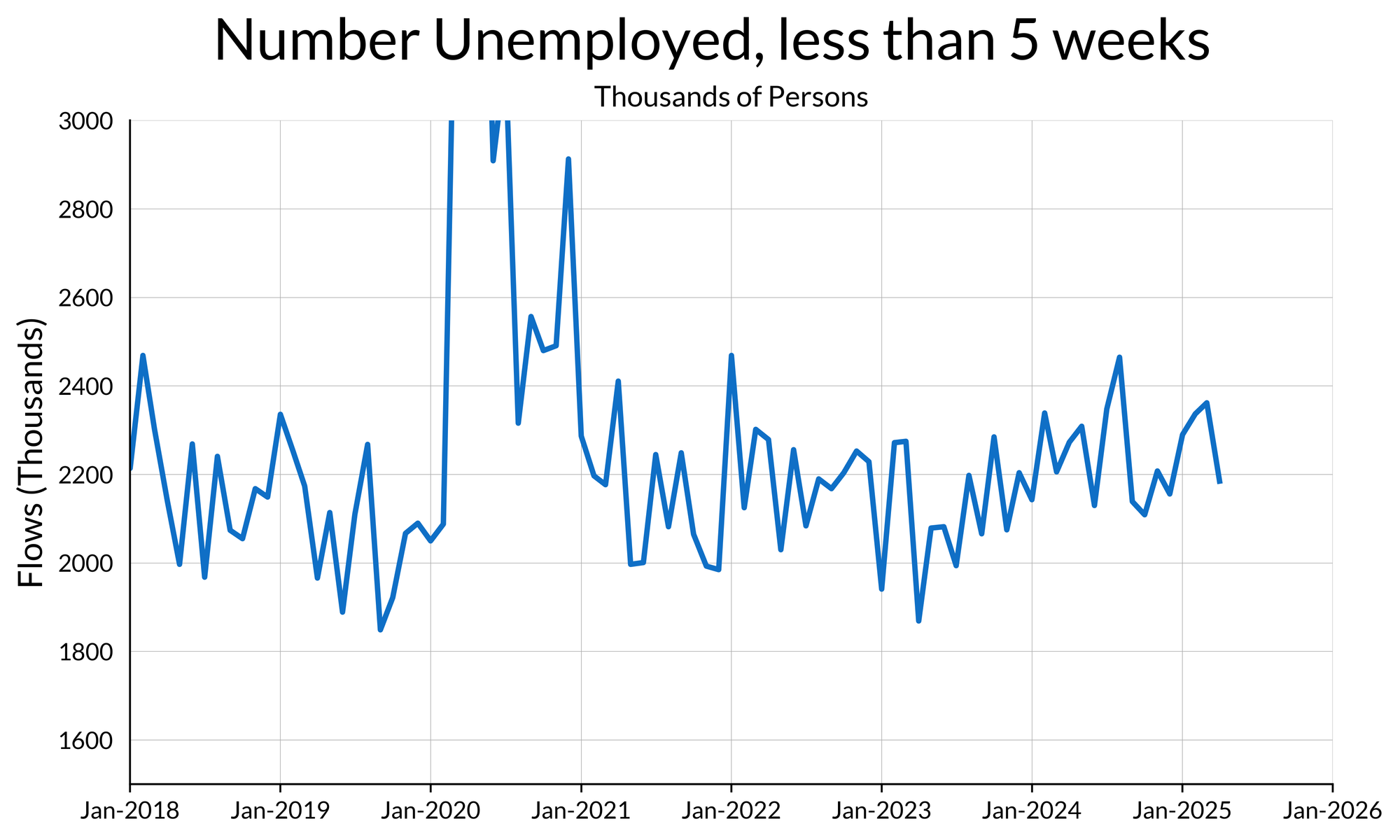

Other finer details of the household survey, such as the prevalence of unemployed permanent job losers and the number of part-time workers for economic reasons do not seem to show any signs of weakness. The household survey’s proxy for recent layoffs—the number of unemployed who have been unemployed for less than five weeks—has retreated.

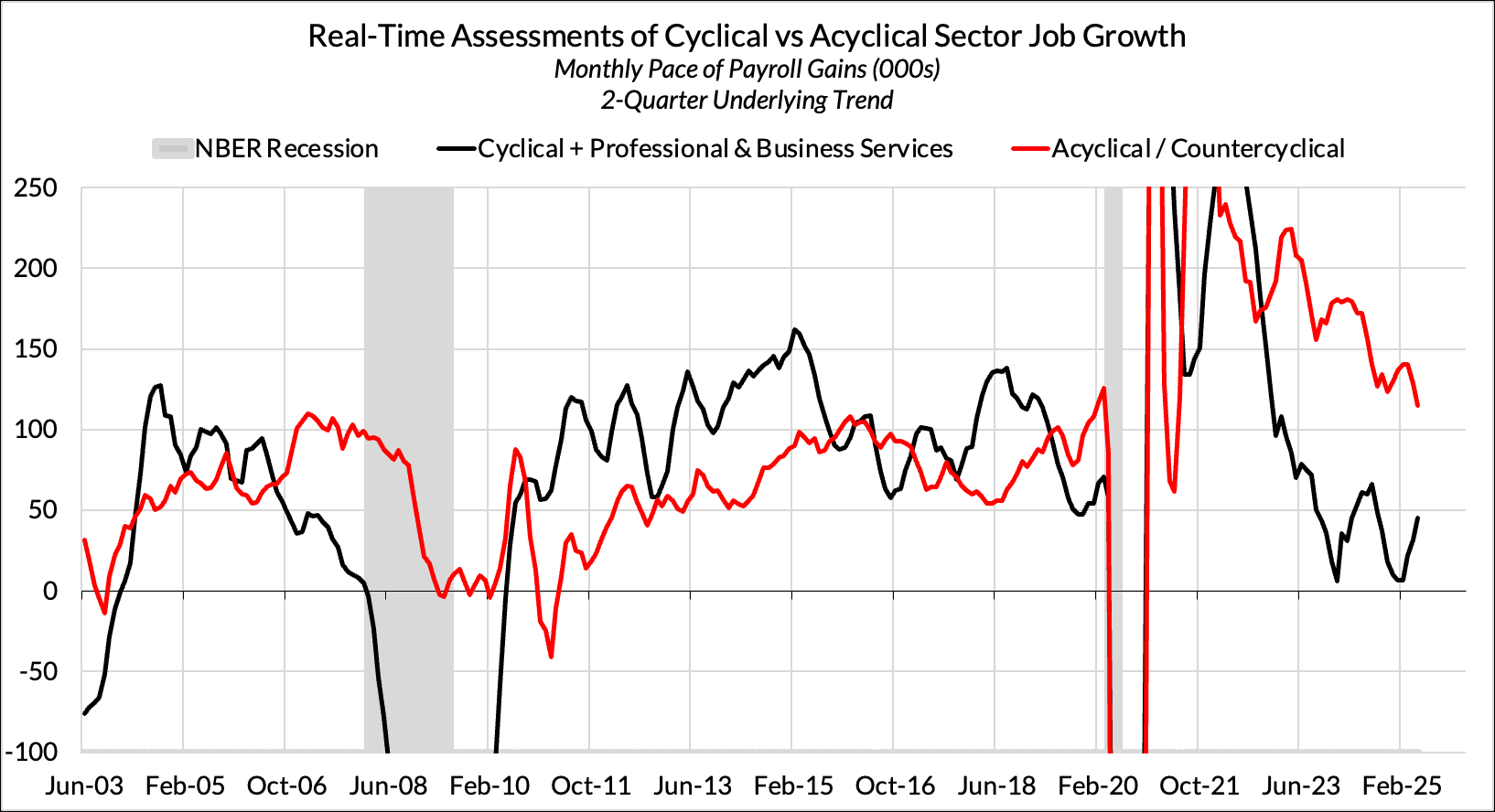

Turning to the establishment survey, the labor market through April 12th (the pay period the survey covers) also appeared mostly strong. Payroll growth was strong, even in the goods-producing and trade-related sectors one would expect to be hit hardest by tariffs. This may be a symptom of businesses front-running tariffs; in any case, it is too early for labor market damage to show up in those sectors.

There was one sign of weakness in the establishment survey: average hourly earnings grew a scant 2.0% annualized in April. This is a noisy number that is subject to revisions, so one should always take a single reading with a large grain of salt. The low growth in wages is concentrated supervisory workers; average hourly earnings growth (it doesn’t seem to be driven by some composition change between these two categories of workers, as aggregate hours growth was similar between all workers and production and nonsupervisory workers).

When will we see labor market damage?

If we haven’t seen a sharp deterioration in the labor market in the April data, when will we see it? While it may be tempting to proclaim an imminent recession (some are saying it’s already here), the labor market seems to be hanging on. The most up-to-date data we have comes from unemployment claims, which we have through most of April. There doesn’t seem to be a huge surge in unemployment claims in recent weeks (there is a spike in initial claims, but that is almost entirely contained to workers in New York affected by Spring Break).

Last week, I wrote about how we could—and usually do—see unemployment increases coming almost entirely from a slowdown in hiring. People generally think about unemployment as a result of people losing their jobs, but that’s only half the story. The way to think about this is that large numbers of people lose their jobs all the time, even during strong labor markets. The reason for a low unemployment rate is that hiring is strong enough that people that do lose jobs find jobs relatively quickly.

We’re coming into the trade war with a low-hiring, low-firing labor market. Over the last couple of years, the hiring rate has fallen almost in lock-step with the quit rate. The result of lower hiring has been felt mostly in terms of lower labor market churn rather than a sharp increase in the unemployment rate.

The low hiring rate has exerted a toll on those already unemployed. While the number of short-term unemployed (less than 5 weeks) has increased by about 10% since early 2023, the number of people who have been unemployed for over 27 weeks has increased by about 75% during the same period. The composition of unemployed has steadily shifted towards the long-term unemployed. Going forward, we will be keeping a close eye on hiring behavior given its ability to move the needle on unemployment.

The Fed will be More Comfortable Waiting

The Fed meets next week, and is expected to hold rates. We expect them to communicate as little as possible about the rate path given the uncertainty over what trade policies will remain in place and what the effects of those policies will be. The strength of April’s jobs data diminishes the probability of a June cut, although it is still in play; as of the time of writing, markets are pricing in a 40% probability of a June cut.

By June, the Fed will see the May employment situation report. Given the strength of unemployment claims through the end of April, we may not see a sharp deterioration in the May labor market data either. If we do see employment start to slip, the Fed starts to enter dangerous territory, where the labor market begins to fall short of their employment mandate at the same time that a supply shock is poised to push up inflation.

The Fed’s tools of interest rate changes and inflation targeting are ill-suited to deal with this situation, and there is a real risk that they get head-faked into keeping policy restrictive as we enter a recession. It would behoove them to look at nominal aggregates to navigate these tradeoffs.