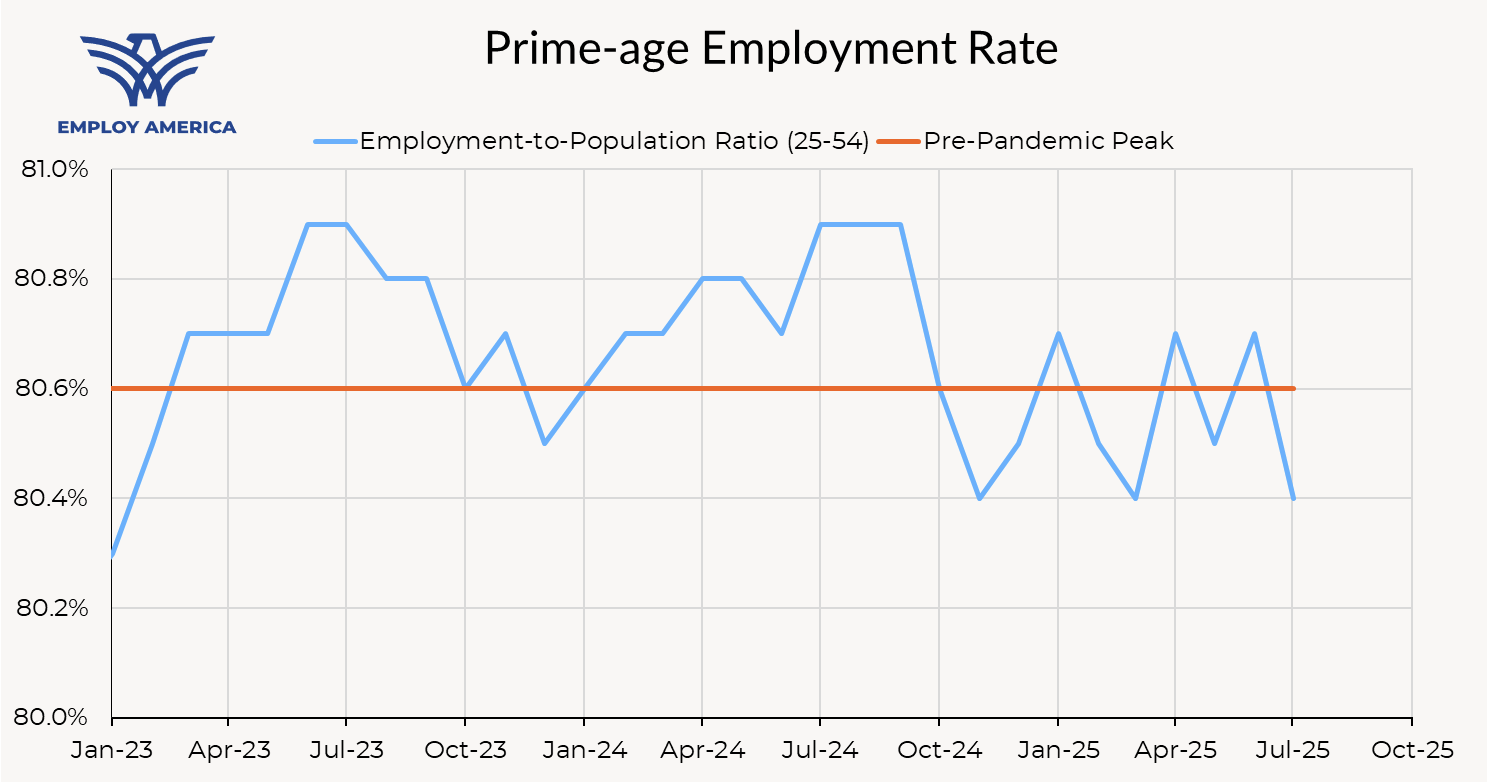

The labor market added 73,000 net jobs in July, with large negative revisions to the previous two months. Job growth was revised downwards by 125,000 and 133,000 in May and June, respectively. Job growth has averaged just over 35,000 jobs per month over the past three months. The negative revisions were spread out over nearly every major sector. The unemployment rate rose by 0.1pp to 4.2%, and the prime-age employment rate fell by 0.3pp to 80.4%. Wage growth was up on the month, but broadly similar to 12 months ago. Quits, hires and job openings were marginally soft in the JOLTS data for June, and layoffs were flat.

This is a soft report. Job growth has slowed sharply, and even if one attributes a large part of that to slowing labor supply from lower immigration, prime-age employment rates are now down 0.5pp from a year ago. This report is weak enough to put a September cut in play, and provides some validation for Governor Waller’s view that the previous couple of jobs reports were overstating the strength of the labor market.

Job Growth is Slowing to a Crawl

The big news out of this report is the negative revisions to the previous two months of payrolls.What looked like strong payroll growth in the previous two months looks basically pre-recessionary now, with just over 35,000 jobs added per month on average over the past three months.

This was a risk highlighted by Governer Waller in his speech last month. He argued that private-sector payrolls were vulnerable to revisions and were actually “near stall speed.” As it turns out, private-sector payroll growth was nearly zero in June.

But private-sector payrolls weren’t the only source of revisions; government payrolls were revised down by even more (proportionately speaking). The state and local government boost to payrolls we saw last month was revised away; government is now representing a drag on payroll employment.

In the private sector, negative revisions were spread out; nearly every major sector saw negative revisions to job growth in May and June. Construction employment is flatlining, and manufacturing employment now looks to be detracting from employment again. While it’s tempting to pin the poor job growth in manufacturing entirely on trade policy, it should be noted that manufacturing has been a drag on employment for months.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

With the hindsight of revisions, the cyclical vs. acyclical industry imbalance of job growth has become even more stark. Cyclical industries (goods-producing, trade and professional and business services) have now seen negative job growth for the last three months. With the weakness in government payrolls, this means that job growth is almost entirely accounted for by growth in healthcare employment.

Household Survey

That’s just the establishment survey, which may need to be graded on a different curve now that immigration is slowing and the “breakeven” rate of job growth may be lower. The household survey, which saw the unemployment rate rise by just 0.1pp to 4.2%, looks better. However, the underlying details are a bit more worrying.

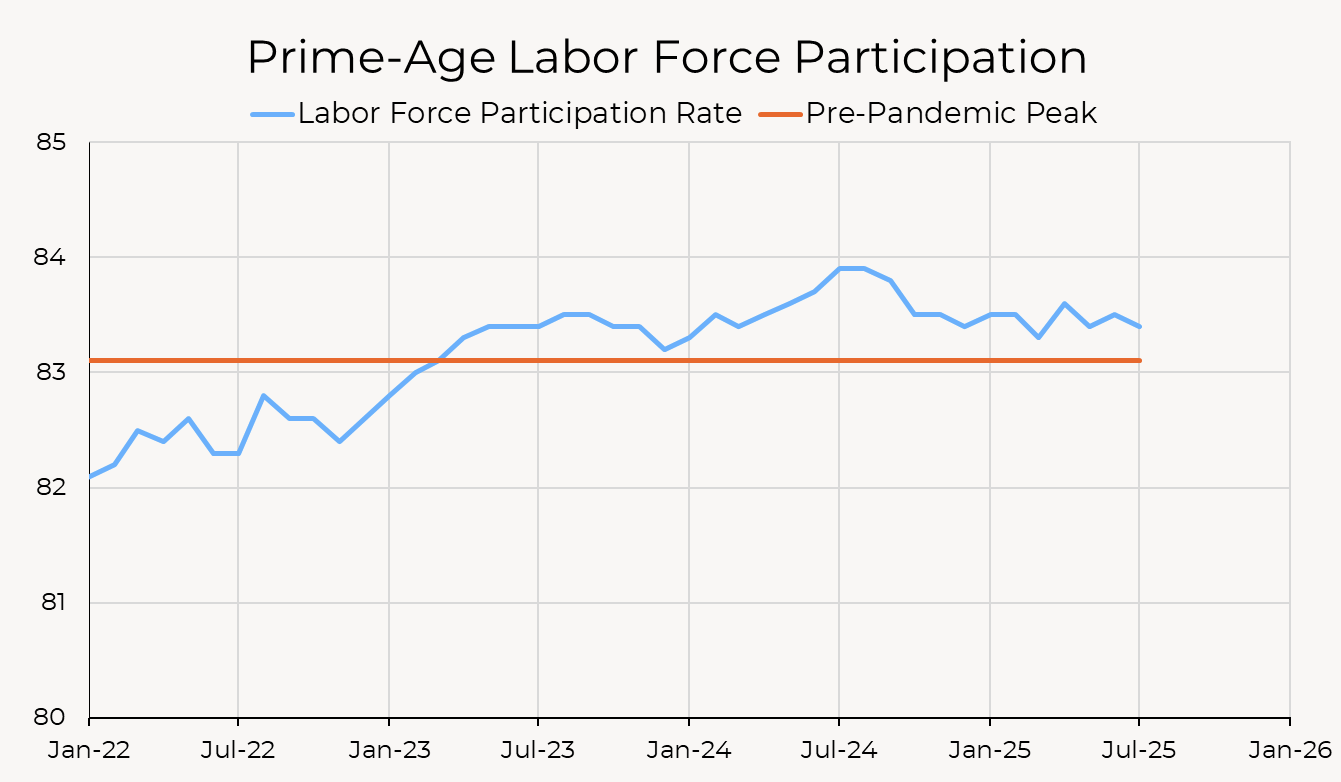

That relatively small rise in the unemployment rate comes alongside a decline in employment and participation rates. The employment-to-population ratio fell by 0.1pp (0.3pp for prime-age); the labor force participation rate fell by 0.1pp (also 0.1pp for prime-age). Over the last twelve months, the prime-age employment rate has fallen by 0.5pp; it rarely falls outside of recessionary and pre-recessionary periods.

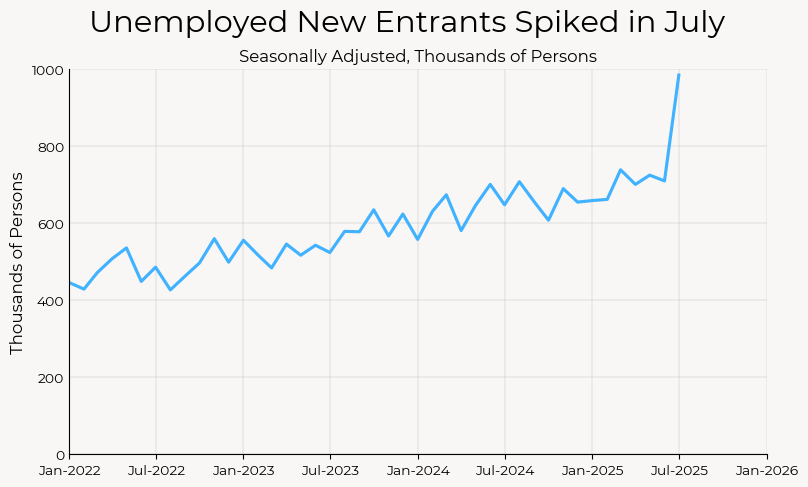

We’re not in the mass-layoffs phase of a labor market breakdown (yet); the low-hiring low-firing state continues. It’s becoming especially apparent when you look at the fringes of the labor market. For example, we saw a huge spike in the number of unemployed new entrants in July.

A spike of this magnitude is likely to reverse next month—in the non-seasonally-adjusted data, usually the number of unemployed new entrants peaks in June and begins falling in July. This year, that didn’t happen. I’d expect the number of unemployed new entrants to begin falling next month, but the delay in hiring and general upwards trend speaks to the labor market weakness plaguing recent college graduates (in case you missed it, check out Will Raderman’s excellent piece at Employ America on recent college graduate unemployment).

Elsewhere, the number of long-term unemployed workers (those unemployed for greater than 27 weeks) is also rising. We haven’t seen this many long-term unemployed (as a percentage of the labor force) since 2017. The average duration of unemployment among those currently unemployed is now 24.1 weeks, up from 20.6 weeks a year ago.

The lack of hiring and firing might result in a “stable” job market, but the lack of churn and hiring means that those who are unlucky enough to be left out of the job market incur long-term costs as the future earnings profile of unemployed workers falls with the duration of unemployment. To the extent that this reflects declining skills, this also harms productivity growth in the long-run.

A September Cut is In Play

It’s not a lock, but the prospect of a September cut is firmly on the table. For months, the Fed has been saying that they’re willing to wait to see what happens with tariff inflation because they see the labor market as strong. If that changes, they may be forced to cut sooner than they’d like. The question is how weak the labor market needs to get before their hand is forced; the payrolls number could be written off as an artifact of immigration, and we may need to see more weakness in the household survey before a cut. For some post-jobs Fedspeak, Bostic says the report raises some concerns but doesn’t think the revisions show that a July hold was a mistake.

The rising pressure from the Administration on agencies like the Fed and the BLS make it harder for the Fed to cut, since cutting in this environment could be seen as giving into external political pressure.

Shortly after the jobs numbers went out, President Trump announced that he directed his team to fire Erika McEntarfer, the Commissioner of the BLS. It goes without saying that this is a terrible development. McEntarfer is not only a tireless public servant but also an important researcher who has contributed greatly to our understanding of how workers of different groups experience the labor market and business cycle. I have cited her work in the past. Her leaving the BLS would be a tremendous loss.