By Skanda Amarnath

Executive Summary

The pricing of the Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) makes it virtually irrelevant for most municipal debt issuers because current market prices are well above those that the Federal Reserve (Fed) is offering. The success or failure of the MLF should be judged not solely by current municipal bond yields, but whether the facility serves to catalyze more issuance. Municipal bond issuance has slowed down in the past three months. In the absence of additional debt issuance or federal aid, the odds of aggressive state and local government austerity is only going to rise further.

State and local government deficits are inevitable when the private sector retrenches in order to run larger surpluses. Yet because of balanced budget requirements, these governments typically undertake aggressive cuts to employment and investment to cope with such deficits. As a result, economic downturns are exacerbated and recoveries proceed slower. The ideal solution to this problem is direct, automatic aid to fill revenue shortfalls.

While borrowing is second-best to direct fiscal aid, it can nevertheless serve as a gap-filling measure that supplements the primary solution of direct, automatic federal aid. Congress should therefore authorize the creation of an external entity backed by the U.S. Treasury that can borrow on behalf of state and local governmental entities. While these state and local officials would be able to direct borrowed funds to as needed to preserve employment and investment during economic downturns, the debt would ultimately be backed by the U.S. Treasury. This would simultaneously overcome challenges posed by municipal balanced budget requirements, while increasing the likelihood that the Fed would purchase such debt as part of its authority to conduct open market operations.

So Much For The Fed Using Its Lending “Cannon”…

The main problem with the MLF is pricing.

The CARES Act gave the Fed authority to lend to a variety of different entities it is not typically authorized to lend to, including non-financial corporations and municipalities. The purpose of delegating such authority was to “provide liquidity,” presumably to help the many businesses and municipalities that were going to face substantial financing gaps amidst historic declines in revenues and incomes.

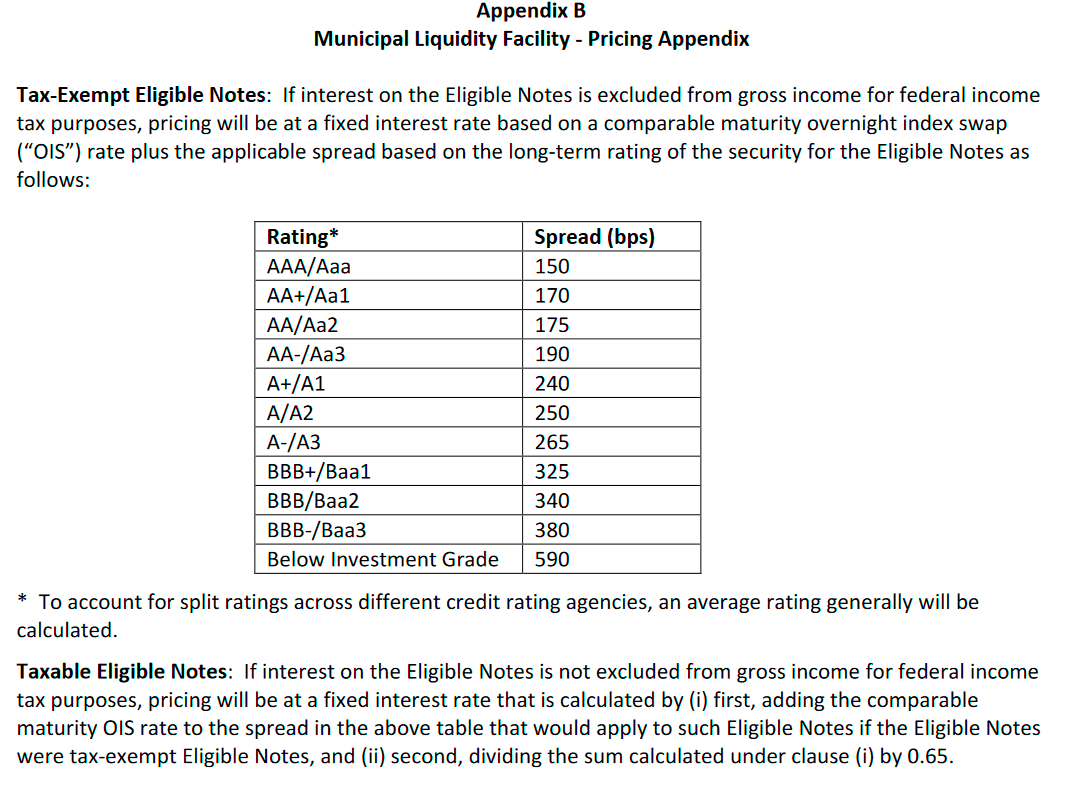

After much hype about the Fed’s bold steps to create and expand the Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) to reach lower-population cities and counties, the latest iteration of the facility’s parameters have been disappointing. The pricing and available maturity for financing through the MLF is especially stingy when compared to what the Main Street Lending Program offers to levered businesses of significantly weaker credit quality.

Instead of serving as an active lender to state and local governments, the Fed’s stiff pricing terms make the MLF only relevant as a “broad-based” facility in a period of extreme financial market turmoil. Anything short of such historic extremes will limit the usefulness of the facility for the vast majority of municipal bond (“muni”) issuers, and especially those with stronger credit ratings.

Only the sliver of governments that are vulnerable to being downgraded into a “junk” credit rating below investment grade are likely to access the MLF based on recent market conditions.

Current asset prices are only useful if they draw out more issuance

Since municipal securities are not typically part of the Fed’s regular open market operations, their issuers, unlike the U.S. Treasury, must be more wary of the effects of additional issuance on their ultimate cost of borrowing. New issuance needs to find new buyers and that usually results in the issuer making price concessions. If the Fed were to make more consistent purchases in the municipal bond market, it could significantly mitigate this dynamic.

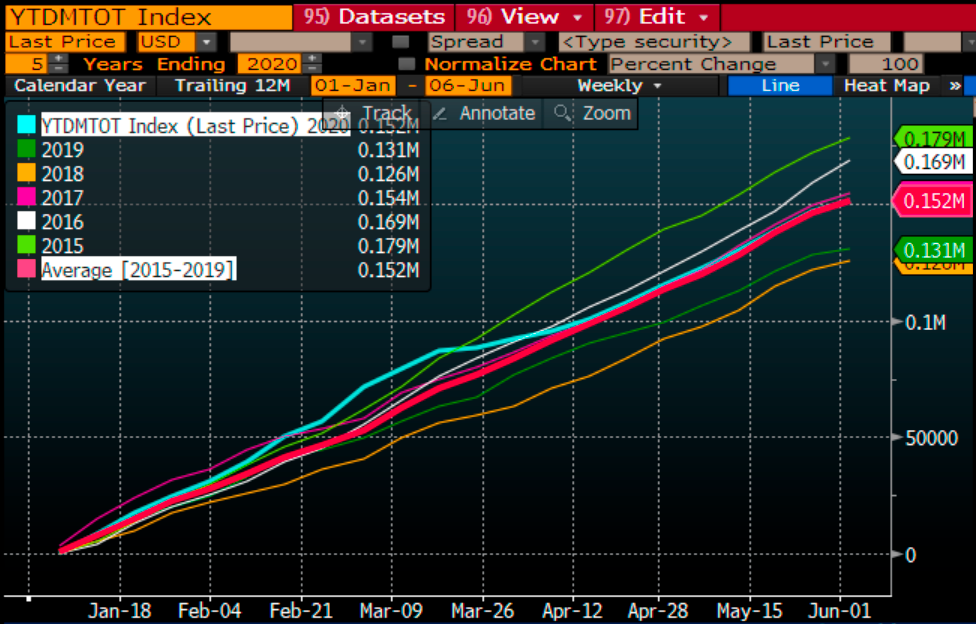

Given the Fed’s mandate from Congress to pursue “maximum employment” and the number of public sector jobs hanging in the balance, the Fed should be judged by its ability to catalyze more muni issuance; current asset prices do not tell the entire story. The recent trends in muni issuance suggest that treasurers are getting less confident about their capacity to issue. After a strong start to the year, issuance has slowed back down to the five-year average, even though municipal yields have fallen over that same timeframe.

State and Local Government Deficits Are Inevitable. Federal Transfers Should Be The Primary Solution

The inevitability of government deficits should be an obvious fact of macroeconomic accounting, but the laws of most state governments fail to grasp this arithmetic reality. Elected officials are often no better.

For every dollar of income an economic actor earns in excess of its expenditure, another actor must be running a countervailing dollar of deficit. Recessions are typically marked by the private sector’s propensity to save more by cutting expenditures relative to incomes. This inevitably leads to (larger) government deficits. Unfortunately, through constitutional and statutory balanced budget requirements (BBRs), state and local governments have straitjacketed themselves into a position where they are forced to cut public services and employment at the very moment the private sector retrenches. When tax revenues fall, these governments are often mechanically compelled to raise taxes and cut expenditures to maintain balanced operating budgets, thereby cannibalizing their existing revenue base. The ability to deficit-finance can play an especially helpful role in preserving and increasing employment (Carlino and Inman, 2013).

If revenue shortfalls could be perfectly anticipated ahead of time, direct transfers from the federal government would be sufficient to overcome any of the statutory or constitutional BBRs that these governments typically impose on themselves. Indeed, the vast majority of lost revenue in a recession should be filled through a straightforward and automatic formula for direct transfers. Please see Alexander Williams’ proposal for how the federal government could set up a direct transfer mechanism to aid state and local governments in economic downturns.

Congress Should Create Municipal Borrowing Vehicles To Preserve Employment In Downturns

While direct aid to states is ideal, no formula will be perfect across all municipalities. There will be still be gaps between revenues and expenditures that, in the absence of additional borrowing capacity, is likely to result in austerity policies that exacerbate economic downturns. While balanced budget requirements and debt issuance limitations constrain municipalities from solving this problem directly, the federal government can offer a comprehensive solution.

Federal-State Hybrid Entities Can Overcome The Obstacles Posed By Balanced Budget Requirements

The federal government already makes its balance sheet available to external entities in a variety of ways. The Development Finance Corporation provides private businesses operating overseas loan guarantees, debt financing, and equity financing. The Unemployment Trust Fund provides state governments a vehicle for borrowing funds (independent of the state government’s balance sheet) for paying out federally mandated unemployment compensation.

A variety of financing and administrative models are possible provided that (1) municipalities retain some control in determining where the borrowed funds are directed and (2) the liability ultimately rests on the balance sheet of the U.S. Treasury, or at least not the balance sheet of the municipality. This avoids the potential conflict with municipal BBRs. In an ideal world, these BBRs would be more flexible during broader macroeconomic downturns, but since they are often constitutionally codified, they are unlikely to change in the near-term.

Such borrowing vehicles should still be subject to the condition that they are used for equitably and efficiently preserving employment and investment during a cyclical economic downturn. A municipality seeking funds must also provide evidentiary basis that it is suffering from revenue shortfalls that were caused by a cyclical economic downturn either at the state or national economic level. If those conditions are met, then the federal government can credit the vehicle with the necessary funds to be directed for the municipality’s specified use.

Financing Backed By The U.S. Treasury Would Increase The Fed’s Willingness To Engage and Support State and Local Governments

Aside from overcoming BBRs, Treasury-backed borrowing vehicles would come with the added benefit of giving the Fed additional comfort with purchasing the securities associated with such borrowing. It is precisely because of the Treasury’s status as ultimate guarantor that the Fed has disproportionately engaged in the market for mortgage-backed securities issued by government-sponsored enterprises.

While there is no statutory requirement that the Fed turn a profit for the Treasury, the Fed chooses to avoid running a loss on its balance sheet out of a sense of political pragmatism. By making the U.S. Treasury the ultimate loss-absorber, Congress would empower the Fed to purchase such debt using its authority under Section 14 of the Federal Reserve Act (Open Market Operations).

It should be reiterated that this program is not intended as a substitute for direct aid to state governments. It is a supplementary gap-filling program that remedies the traditional problem of federal aid coming a day late and a dollar short of what’s usually needed. Even if Congress implemented state aid as an automatic stabilizer triggered by transparent macroeconomic data, no formula or trigger for filling lost tax revenue will be perfect across all governmental entities. To prevent such entities from holding the bag in such a scenario, it would be prudent to have a foolproof mechanism for ensuring that they are able to address desperate expenditure needs in the midst of macroeconomic downturns.