Authors: Skanda Amarnath & Sudiksha Joshi

The previous post made the case for why the Evans Rule, when evaluated in the full context of fiscal austerity and a deleveraging household sector, was an underrated policy success. Here, we discuss six potential improvements to the Evans Rule that the Federal Reserve (Fed) should consider as it formulates its forward guidance strategy in response to the COVID-19 economic crisis.

Summary

While the Fed’s capacity is more limited when interest rates are already at the zero lower bound (ZLB), it can still play a powerful supporting role by concretely committing to keep interest rates low for as long as is needed to achieve a full recovery in employment and wages. The ideal policy for the Fed to adopt right now is a commitment to keep the federal funds rate at the zero lower bound so long as long-term inflation expectations remain anchored at (or below) 2% and the following two conditions hold:

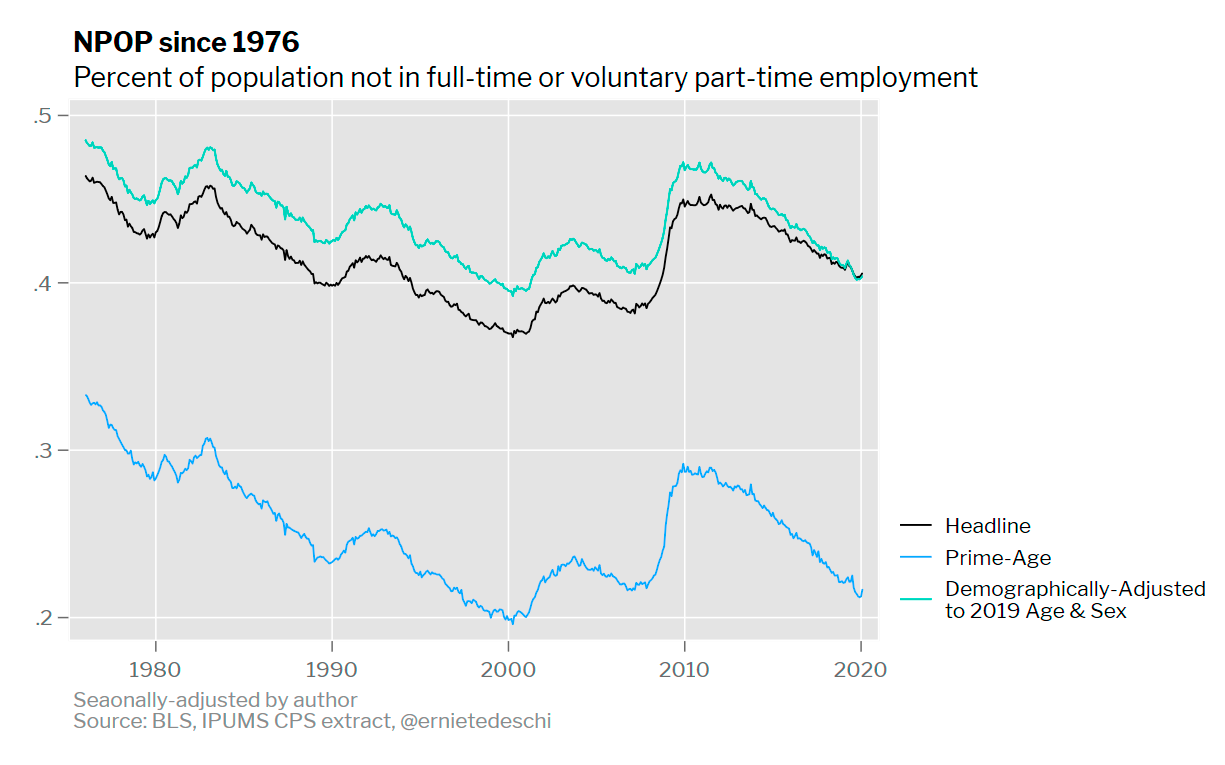

- Labor utilization, preferably measured using the prime-age 25–54 employment-to-population ratio or Ernie Tedeschi’s demographically-adjusted NPOP measure, remains below the level achieved in the fourth quarter of 2019 (80.3% and 40.2% respectively).

- Wage growth, preferably measured using the employment cost index for either wages and salaries or total compensation, remains below its year-over-year growth rate in the fourth quarter of 2019 (2.7% and 3.0% respectively).

The Fed should also be willing to revise these thresholds quickly when it becomes clear that more labor market progress is achievable, or if the chosen indicators seem to exhibit some distortions. Dynamic revision is particularly helpful if the Fed initially opts for less ambitious thresholds than what is suggested above.

Our proposed set of improvements:

- Replace the focus on price inflation projections with an emphasis on nominal wage growth. Instead of relying on internal projections of future consumer price inflation, the Fed should tie forward guidance to realized wage growth using the employment cost index. By relying on opaque projections of consumer price inflation, the Evans Rule diminished the extent to which forward guidance could have shaped expectations about the future path of interest rates. While market participants and economic actors can more transparently observe actual price inflation readings, these readings can be highly volatile and idiosyncratically driven, thereby resulting in more arbitrary policymaking. Given the speed and depth of the economic shock associated with COVID-19, price inflation readings are even more likely to be volatile in the current environment, misleading policymakers with one-off methodological quirks. Unlike price inflation, wage growth is more sensitive to changes in labor utilization and economic activity.

- Replace the ceiling with a floor. The systematic problem with Fed policy over the past decade has been insufficient nominal income growth, not excess inflation. The inflation component of the Evans Rule was set up as a ceiling; only if projections of inflation exceeded 2.5% would the Fed exit its zero interest rate policy (ZIRP). While a ceiling is more politically intuitive in the context of price inflation (who deliberately wants to see more price inflation?), a baseline floor is the better approach with respect to wage growth. Aiming for a floor rate of price inflation may be functionally workable, and Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker even suggested as much in a recent speech, but wage growth is a more politically attractive benchmark when the true objective is to actively “heat up” the economy.

- The labor utilization threshold should be a necessary “level target” condition but not an individually sufficient condition for ending state-based forward guidance. While the validity of the Phillips Curve and the natural rate of unemployment rate have been rightfully questioned in recent years, the Fed should retain a baseline target for labor utilization. In its absence, any threshold that solely turns on the rate of price inflation or nominal wage growth is vulnerable to the the “level versus change” problem that Neil Irwin recently highlighted. We’ve seen a precipitous drop-off in economic activity followed by bits and pieces of recovery. While monthly developments are optically extreme in terms of growth rates, the overall level of economic activity provides a more stable and holistic picture. The case for adopting some form of a level target is stronger in the context of the current crisis as a result. Provided that “longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored,” achievement of both the thresholds for wage growth and labor utilization should be a necessary condition for ending forward guidance. While there is some risk that consumer prices accelerate before labor utilization nears its specified threshold, retaining the Evans Rule’s escape clause regarding inflation expectations curbs the risk of a sustained de-anchoring to the upside. The Fed has continued to reiterate that its 2% inflation target is a symmetric target, in which case there should be some additional tolerance for above-target inflation in light of their systematic bias for below target inflation.

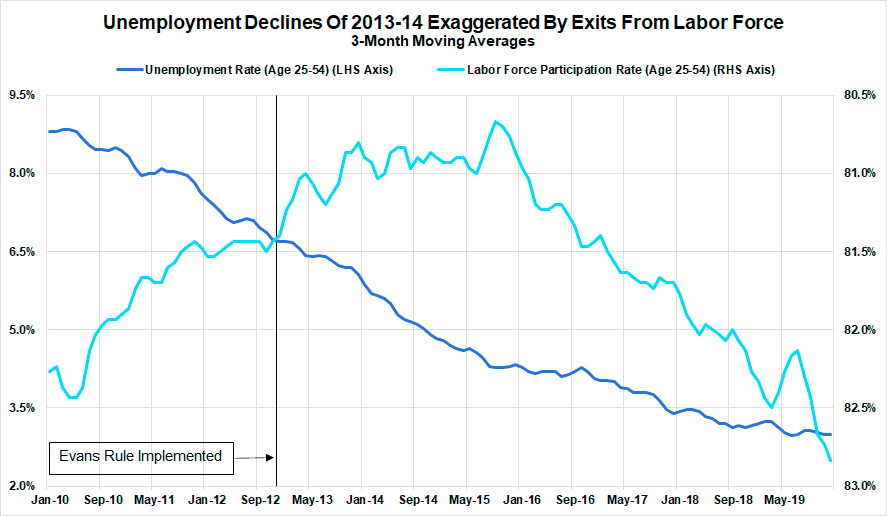

- Choose a more robust measure of labor utilization than the U-3 unemployment rate. The impact of the Evans Rule was stymied by the choice of the U-3 unemployment to capture labor utilization. The unemployment rate declined surprisingly quickly in 2013 because measures of labor force participation were also declining at the same time. Those declines in participation ultimately reversed course later in the business cycle expansion but nevertheless impacted forward guidance based on the Evans Rules. The prime-age 25–54 employment-to-population ratio would serve as a straightforward solution to this flaw because it does not rely on the blurry distinctions between nonparticipants and the unemployed, which are difficult to categorize consistently in the Current Population Survey. Ernie Tedeschi’s demographically-adjusted “NPOP” series, while more complicated and less well-known, would be ideally suited to capture the full magnitude of labor market slack, including those who are part-time underemployed.

- Initially presume against “structural” shifts. If the Fed proceeds with quantitatively defined state-based forward guidance in the form of Evans Rule thresholds, it should presume against any notion that there has been a sudden rise in structural unemployment or a structural decline in the level of sustainable wage growth. The purpose of a reformulated Evans Rule should be to recover the labor market that preceded the onset of COVID-19, when the prime-age 25–54 employment-to-population ratio was above 80% and the employment cost index was growing at approximately 3% year-over-year. The economy was not suffering from overheating prior to the onset of the pandemic. If anything, the systematic under-performance of inflation and wage growth suggested that monetary policy could continue to err on the side of accommodation. While there are always interesting stories about how the world has fundamentally changed since the pandemic, the wrongheaded claims following the Great Recession about structural unemployment should serve as a cautionary tales.

- Revise the thresholds in the face of new information about the labor market. The Fed had to continuously revise down their estimates of the natural rate of unemployment in the years following the Evans Rule. Chair Powell even admitted that the Fed had systematically underestimated the potential for greater labor market progress without aggravating inflationary pressures. If the Fed chooses to adopt more conservative thresholds, then it should at least be willing to revise such thresholds in the absence of upward inflationary pressures. The prior expansion should be instructive here; higher labor utilization and wage growth were not associated with sustained above-target consumer price inflation. If we learn that the economy has more spare capacity, the Fed should move briskly to adjust to that reality.

Wage Floors, Not Price Ceilings

The Evans Rule was a qualified success, but if the Fed goes down the path of quantitative state-based forward guidance, there are still lessons to be learned. While the calibration of the rule in terms of a labor utilization metric and a nominal variable were a reasonable way to balance the Fed’s mandated objectives for maximum employment and price stability, it could have chosen better indicators to match those objectives.

Nominal Wages Deserve More Attention Than Consumer Prices, Projected or Actual

When the FOMC was first contemplating the Evans Rule, the debate was mostly concerned with curbing the risk of excess price inflation. A potential rise in structural unemployment and an elevated balance sheet were among the factors cited for why the economy was at risk of rising inflation. For these reasons, the Fed adopted an “inflation ceiling” as part of the Evans Rule:

“the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as…inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal”

The inflation ceiling was expressed as a forecast, and not as actual inflation readings that are released each month. Fed staff rightly acknowledged that realized inflation readings were too volatile for reliably calibrating quantitative thresholds for state-based forward guidance. The reliance on an inflation projection was meant to help “look through” some of the local volatility in current inflation readings.

Yet the use of an opaque inflation projection ultimately defeats some of the potential benefits of state-based forward guidance. Forward guidance works to the extent it shapes the expectations of economic actors, but how should economic actors understand FOMC members’ projections for price inflation? Each member is likely to have a different model and theory regarding the factors driving inflation . These models and theories are further complicated by the heterogeneity of methodologies applied to component price indices, and are subject to revision over time in order to incorporate new forms of hedonic adjustment.

Spot and projected consumer price inflation are ill-suited to the local and structural challenges of macroeconomic policy. The Fed would be better off adopting quantitative thresholds that are rooted in nominal incomes or wages instead. Unlike consumer price indices, the employment cost index follows a much more consistent methodology over time. The employment cost index is also especially helpful for avoiding problems that plague other measures of wage growth, including selection biases, small sample size challenges, and aggressive revisions to previously reported data. Most importantly, wage growth is sensitive to developments in the broader economy in a way that consumer price inflation is not.

The Case For Floors Instead of Ceilings

Instead of setting a “ceiling” over projected consumer price inflation, a reformulated Evans Rule should be set as a “floor” under nominal wage growth, as measured by the employment cost index for either total compensation or wages and salaries. The inflation ceiling in the original Evans Rule was never breached during or after the period when the Evans Rule was in effect. If the Fed actually wants to escape the asymmetric costs of the ZLB, it will have to take affirmative steps to help engineer higher rates of nominal income and spending growth. An active floor is aligned with this objective in a way that the Evans Rule’s passive inflation ceiling was not.

Some FOMC members are already thinking along these lines. Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker suggested that the FOMC should condition any exit from ZIRP on first achieving 2% inflation. If not for some of the measurement quirks that plague inflation readings, such a precondition could be effective. But even if one looks beyond these quirks, there is a deeper question of political optics and intuitive communication that the Fed should consider carefully.

At a time when nominal income growth is historically weak, fixating on the rate of consumer price inflation confuses the objective with the byproduct. The problem of the past decade and the current context is one of inadequate nominal incomes, not insufficient price increases. The Fed has systematically undershot the 2% inflation target it adopted in January 2012, but the true cost of this policy failure is reflected in the abysmal pace of wage growth, which barely reached 3% during the previous expansion. Thus, in spite of historically low interest rates, economic outcomes of the past decade reveal that the Fed has consistently erred on the side of excessively hawkish policy.

If the Fed wants to end this era of chronically low inflation and income growth, an exit from ZIRP should be conditioned on achieving a sustainable rate of nominal wage growth. In the absence of accelerating nominal wage growth, upward pressures on price inflation alone merely reflect relative price changes.

The Role of Labor Utilization In State-Based Forward Guidance

The irony of the Evans Rule was that the component of the rule that was conventionally viewed as dovish, the unemployment rate threshold, actually proved to be the most hawkish in retrospect. David Andolfatto and Narayana Kocherlakota were among the outliers in foreseeing this dynamic. If the Evans Rule only involved an inflation threshold, the Fed’s urge to increase interest rates would have been kept at bay for a much longer period of time.

Of course, any policy rule must take into account alternative scenarios and not simply the ones that have played out. The memory of both 2008 and 2011 must have been fresh in the minds of policymakers, when oil prices and inflation readings temporarily surged amidst deteriorating economic conditions. Surely the last thing that some of the more vocal doves like Charles Evans and Eric Rosengren wanted to see was another red herring inflation surge distracting from the more glaring implications of elevated unemployment. Yet even in this scenario, the implementation of the labor utilization threshold within the Evans Rule was far from optimal.

The Labor Utilization Threshold As A Level Target — Necessary, But Not Sufficient For Ending Forward Guidance

The original Evans Rule was framed as an either-or proposition: either the unemployment rate falling below 6.5% or price inflation projections exceeding 2.5% would end the Fed’s state-based forward guidance policy. Yet even as the unemployment rate declined past 6.5%, there were few signs of a sustained acceleration in prices. Actual inflation readings barely reached 2% and never sustainably reached the 2.5% ceiling even in the years after the Evans Rule when the unemployment rate reached 3.5%. It took another four years after the conclusion of the Evans Rule for hourly compensation to grow at a rate roughly consistent with 2% inflation and a 1% growth rate in productivity.

The relevance of a labor utilization threshold would have been much more powerful if achievement of both Evans Rule thresholds were a necessary condition for ending state-based forward guidance with respect to ZIRP. This would make Region 2 and Region 3 of David Andolfatto’s grid the same as Region 4.

This aggressive approach to forward guidance might not have been politically feasible in December 2012 given that the hawks on the FOMC were also worried that the inflation ceiling in the Evans Rule was too high for it to be the pathway for ending forward guidance. Current FOMC members might be more open to such an approach, especially if the Fed substituted a wage growth floor for the prior inflation ceiling.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is tempting to claim that there never should have been a labor utilization component of the Evans Rule in the first place. The validity of the Phillips Curve and the natural rate of unemployment rate looks increasingly questionable; even as the unemployment rate achieved new lows through the expansion, wage growth and price inflation also remained historically low.

However, in volatile macroeconomic environments, a snapshot of growth rates (whether in terms of wages, prices, output, or employment) rarely tells the full story. May and June saw the strongest nonfarm payroll growth in over 70 years!

Nonfarm payroll employment is still nearly 10% below its February peak.

While I could reiterate some of the technical arguments for level targeting schemes, the case for targeting a specific level of labor utilization is rooted in a simpler purpose: retaining context. Short-term shifts in economic activity can appear optically extreme in terms of growth rates, but the level of economic activity provides a more stable and holistic picture. The case for adopting a level target is stronger in the context of the current crisis because of the unpredictable nature of the public health crisis and its historic impact on economic activity.

The risk associated with the suggested approach would be a significant overshoot of the 2% inflation target prior to reaching the chosen labor utilization threshold. In light of the Fed’s systematic bias for below-target inflation, the Fed should be comfortable with some risk of an inflation overshoot if it is committed to symmetric outcomes around the 2% target, as long as long-term inflation expectations appear reasonably anchored. Should long-term inflation expectations show some vulnerability to the upside as a result of a an overshoot, the Fed should have the option, just as they did with the Evans Rule, to adjust accordingly. That said, the fact that long-term inflation expectations stayed anchored amidst the string of downside misses over the past decade suggests there should be commensurate tolerance for upside surprises.

Moving Past The Unemployment Rate

The first major error of the Evans Rule was to calibrate ZIRP according to the level of the unemployment rate. While changes in the unemployment rate are a valuable indicator of cyclical inflection points, the Current Population Survey (CPS), from which the unemployment rate is derived, is not able to consistently delineate the unemployed from labor force nonparticipants. As a result, labor force participation is not as well-defined in practice as it is in concept.

This weakness in the Evans Rule was exposed in 2013, when the unemployment rate fell rapidly due to declining labor force participation rather than stellar job growth. As a result, the Evans Rule was in place for a much shorter time than it should have been.

The Evans Rule met its premature end in March 2014, and the Fed spent most of 2014 and 2015 laying the groundwork for raising interest rates, which helped stoke a historic appreciation of the US dollar against foreign currencies and ultimately fostered a slowdown in exports and business fixed investment.

There are superior labor utilization metrics that cut through this measurement problem associated with the headline U-3 unemployment rate. Employment-to-population ratios (EPOPs) are invariant to the distinction between unemployment and nonparticipation. While the headline employment-to-population ratio does not adjust for age composition, focusing on the prime working age (25–54) cohort offers a simple but effective adjustment. The commensurate declines in prime-age EPOP associated with a 1.3% decline in the unemployment rate took an additional year to achieve. Had the Evans Rule been in place for that period, the 2014–16 economic slowdown would likely look very different.

Although not as mainstream as prime-age EPOP, Ernie Tedeschi’s demographically-adjusted NPOP would be the ideal labor utilization metric for formulating state-based forward guidance. Tedeschi’s measure involves a more comprehensive and systematic adjustment for demographic shifts. NPOP also accounts for changes in part-time underemployment, a form of labor market slack that is likely to be especially elevated given the nature of the current economic shock. EPOPs alone do not take into account this dynamic.

Setting The Evans Rule Thresholds With Appropriate Generosity

When FOMC first debated the Evans Rule in 2012, the 6.5% threshold for the unemployment rate was aggressively contested. Some FOMC members saw the urgency of accommodative policy because unemployment was so elevated. Others were of the belief that structural unemployment had subsequently increased due to a variety of other factors and thus the Fed should withdraw some of its historic accommodation.

Calibration Strategy #1: Back To the Pre-COVID-19 Labor Market

If the Fed proceeds with a reformulated Evans Rule, then the initial calibration of the rule should not assume that structural unemployment or trend productivity growth have meaningfully shifted.

Demand-based thinking might be seen as the dominant flavor of the day, but supply-side narratives about recessions tempt policymakers as well. Philadelphia Fed President Charles Plosser saw the primary problem as one of mismatched skills within the labor force relative to the needs of society. Richmond Fed President Jeffrey Lacker even went so far as to claim that drug use and generosity of unemployment benefits were the primary causes of elevated unemployment in 2011. That the unemployment rate ultimately reached a low of 3.5% without aggravating sustained inflation shows how misguided this thinking proved to be.

Even some of the more dovish members of the FOMC were guilty of similar thinking with respect to productivity growth. Despite the absence of inflationary pressures, FOMC members extrapolated from recent productivity data to claim that wage growth was justifiably stunted. With the strong caveat that productivity data is very noisy and distorted, the final years of the 2010s expansion generally saw productivity accelerate to its fastest pace since the initial phase of the expansion when jobs were still being lost.

The purpose of a reformulated Evans Rule should be to recover the labor market that preceded the onset of COVID-19, when the prime-age 25–54 employment-to-population ratio was above 80% and the employment cost index was growing at approximately 3% year-over-year. While it is possible that there are structural shifts that complicate the achievement of those goals, it will be some time before we can do more than speculate. In the absence of such shifts, recovering the labor market of the fourth quarter of 2019 should be the Fed’s primary goal.

Prior to the onset of this pandemic, the economy was not suffering from overheating. If anything, the systematic under-performance of inflation and wage growth suggested that monetary policy could continue to err on the side of accommodation.

Calibration Strategy #2: Dynamically Revising Thresholds

At the risk of solving for suboptimal choices, if the Fed initially sets more conservative goals than what is suggested above, then it should be willing to dynamically revise those goals if more progress appears achievable. For example, if wage growth and price inflation fail to accelerate even as labor utilization rises, then the Fed should strengthen its forward guidance by setting more ambitious goals for labor utilization.

Revising the labor utilization threshold was an obvious remedy to the flaws intrinsic to the original Evans Rule. At the December 2012 FOMC Meeting when the Evans Rule was implemented, the unemployment rate was 7.7% and inflation was still running below its recently-adopted 2% target. But even as the Evans Rule was announced, flaws with the unemployment rate as a labor utilization gauge were emerging.

Much of the decline in unemployment that occurred over the course of 2013 was driven not by faster hiring but by a reclassification of the unemployed into labor force non-participants. With current knowledge of just how blurry these boundaries actually are, the ideal remedy would have been to switch to a better measure of labor utilization like the prime-age employment-to-population ratio.

As a second-best remedy, the FOMC should have been willing to move the goalposts, since the hollowing out of labor force participation was not actually proving to be inflationary. Declining unemployment at the expense of labor force participation was not providing us with any price signal to suggest a seriously tight labor market. Throughout 2013, core and headline inflation readings remained stable and below the Fed’s 2% inflation target while the employment cost index was still growing at less than 2% year-over-year. Beginning in September 2013, FOMC members began to continuously, albeit slowly, revise down their estimates of the natural rate of unemployment. However, in spite of these revisions, the Committee maintained its 6.5% unemployment threshold for defining the conclusion of state-based forward guidance for ZIRP.The confluence of these phenomena should have motivated the Fed to revise the Evans Rule unemployment rate threshold below 6.5%.

Chair Powell has recently admitted that the Fed had systematically underestimated the scope for how much labor market progress was feasible without aggravating inflationary pressures. Despite this awareness, the FOMC remains slow to adjust to changing information about the state of the labor market. If the Fed chooses to adopt more conservative thresholds, then it should at least be willing to revise such thresholds reasonably swiftly. The prior expansion should be instructive in this regard; higher labor utilization and wage growth were not associated with sustained above-target consumer price inflation.

Conclusion

While the Fed does face some constraints on its ability to affect the economic trajectory, it nevertheless still has power to support the economy and should exercise that power to foster a quick and full recovery from this public health and economic crisis. During the last three recessions, it took several years for labor utilization to stop declining generally, and still more to see something resembling a full recovery from the employment losses of the recession. It would be both a fiscal and monetary policy failure to see yet another sluggish recovery following the resolution of this pandemic. To that end, we suggest these six improvements to the Evans Rule as the Fed considers the merits and structure of state-based forward guidance:

- Replace the focus on price inflation projections with an emphasis on achieving nominal wage growth as measured using the employment cost index for compensation or wages & salaries.

- Floors, not ceilings: the Evans Rule’s ceiling threshold for projected inflation should instead be applied as a floor threshold, and preferably with respect to wage growth instead of consumer price inflation.

- The labor utilization threshold should be a necessary “level target” condition and not an individually sufficient condition for ending state-based forward guidance.

- Choose a more robust measure of labor utilization than the U-3 unemployment rate. The prime-age 25–54 employment-to-population ratio and Ernie Tedeschi’s demographically-adjusted NPOP measure would both be superior to the U-3.

- Initially presume against “structural” shifts when calibrating forward guidance thresholds. The most appropriate thresholds for recovering the labor market are a 3% floor threshold for wage growth and a 80.3% floor for the prime-age 25–54 employment-to-population ratio.

- Revise the thresholds dynamically in the face of new information about labor market progress.