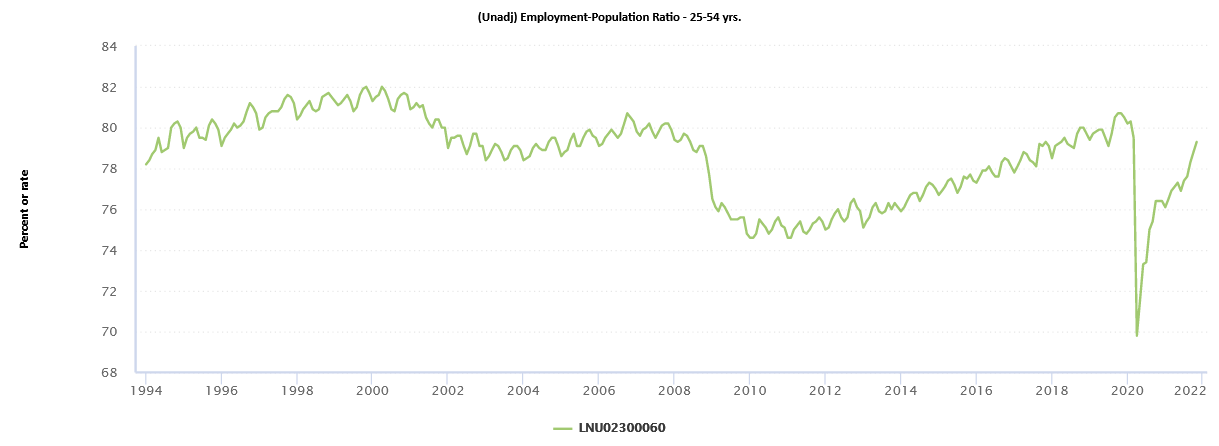

The prime-age employment rate rose by 0.5% in November 2021 to 78.8%, but this was abnormally low relative to the not seasonally adjusted (NSA) estimate of 79.3%. The 2019Q4 peak was 80.3%. The next employment report will feature seasonal factor revisions in the household survey (the subsequent employment report will feature the major annual benchmark revision in the establishment survey). We are likely closing in on pre-pandemic employment rates faster than is generally appreciated.

For those familiar with our work, you'll know that we prefer emphasizing the prime-age 25-54 employment rate (employment-to-population ratio) when evaluating each jobs report. It's great for adjusting for the following key nuances:

- Changes in age structure. The population is aging and so too is retirement propensity.

- Labor force participation measurement bias, which over-classifies workers as "not participating in the labor force," especially during recessions and recoveries, and thereby artificially compresses the headline unemployment rate.

- Avoiding the problem of revisions. Nonfarm payrolls, derived from the establishment survey (CES), should theoretically be a more robust measure of labor market health but gets heavily revised each month and only belatedly reveal key labor market dynamics. It's true that household survey estimates tend to be more volatile than the establishment survey, such that it helps to use a moving average, but what you see is what you'll get (with the key exception that annual seasonal factor revisions will be implemented in next month's employment report).

There are some blindspots with the prime-age employment rate, but for the time being, prime-age employment rates are similar to adjacent cohorts (20-24, 55-59, 60-64) and part-time underemployment does not appear to be abnormally elevated.

Employment Rate Gaps adjacent to prime-age cohorts

— Skanda Amarnath ( Neoliberal Sellout ) (@IrvingSwisher) December 3, 2021

55-64: 1.6% below peak (NSA)

55-59: 1.7% below peak (NSA)

60-64: 1.2% below peak (NSA)

20-24: 1.6% below peak (SA) pic.twitter.com/i588BVj2pX

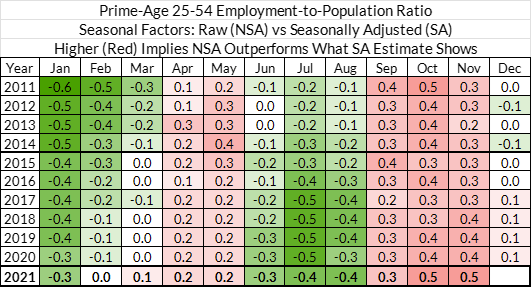

We are approaching that time of the year when even even the prime-age employment rate readings for the past year are going to be revised. No new observations will be unearthed, but the BLS needs to revise the factors it associates with seasonal patterns each year.

Employment trends typically exhibit very obvious seasonal patterns, even though the process of raising employment in 2021 has been surprisingly linear and not as obviously seasonal to the naked eye.

Seasonal adjustment methods are now abnormally understating the prime-age 25-54 employment rate for November. The seasonally adjusted estimates are now attributing 0.5% of the not seasonally adjusted estimate, when the typical November is closer to 0.3%. Should the raw (not seasonally adjusted) employment rate stay flat at 79.3% in December (no net hiring), the typical seasonal factor would yield 79.2% (0.1% below the NSA 79.3%).

Just as a hypothetical (and NOT as a forecast): if the raw prime-age employment rate was flat through January (no net hiring), it would be approximately 79.6%, just 0.7% from the 2019Q4 pre-pandemic peak.

The 2021 seasonal factors are also likely to be revised, such that we will see each monthly reading this year potentially move by one to two tenths of a percentage point. These revisions are not substantial on their own, but they are worth flagging in light of the asymmetry associated with the current reading.

For employment rates to rise meaningfully over the next two months in seasonally adjusted terms, retention might prove more marginally important than hiring. Many sectors hire aggressively in November ahead of the holiday season and layoff workers as the holiday season comes to a close in January (when seasonally adjusted estimates are typically 0.3% to 0.5% above the raw not seasonally adjusted estimates).

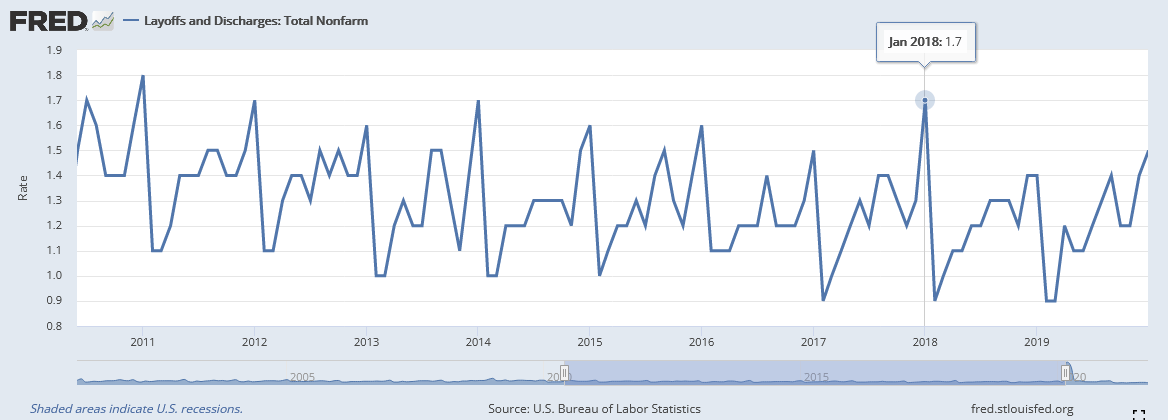

Layoff patterns in seasonally adjusted terms have been atypically low in 2021, confirming the reports of workforce challenges and labor shortages. In the latter half of the 2010s, the JOLTS nonfarm layoff rate was a steady 1.2% on average. In the latter half of 2021, the nonfarm layoff rate has settled in around 0.9% on average.

Layoff rate is historically low, as firms prioritize retention (compare 2010s to recent months)

— Skanda Amarnath ( Neoliberal Sellout ) (@IrvingSwisher) December 8, 2021

January typically sees a surge in seasonal layoffs but seasonal patterns are also shifting. If Jan layoffs are relatively low, seasonally adjusted estimates of employment will pop pic.twitter.com/7ukWvmGxTr

We typically see in seasonal layoffs ramp up in December and January, such that the layoff rate--when not seasonally adjusted--is always quite strong in those particular months of the calendar year.

If firms respond to the current signs of labor market tightness with greater emphasis on retention, the headline jobs numbers and the pre-pandemic employment rates are likely to show significant gains.

With seasonal factors changing more rapidly at this time of year and the upcoming revisions--both to seasonal factors in the household survey and to the nonfarm payroll estimates in the establishment survey--it's important to strap in for a bumpy ride. What we see now in the official labor market statistics is likely to look substantially different within two months. We remain cautiously optimistic that age-adjusted employment rates can continue to rapidly close in on their pre-pandemic peaks.