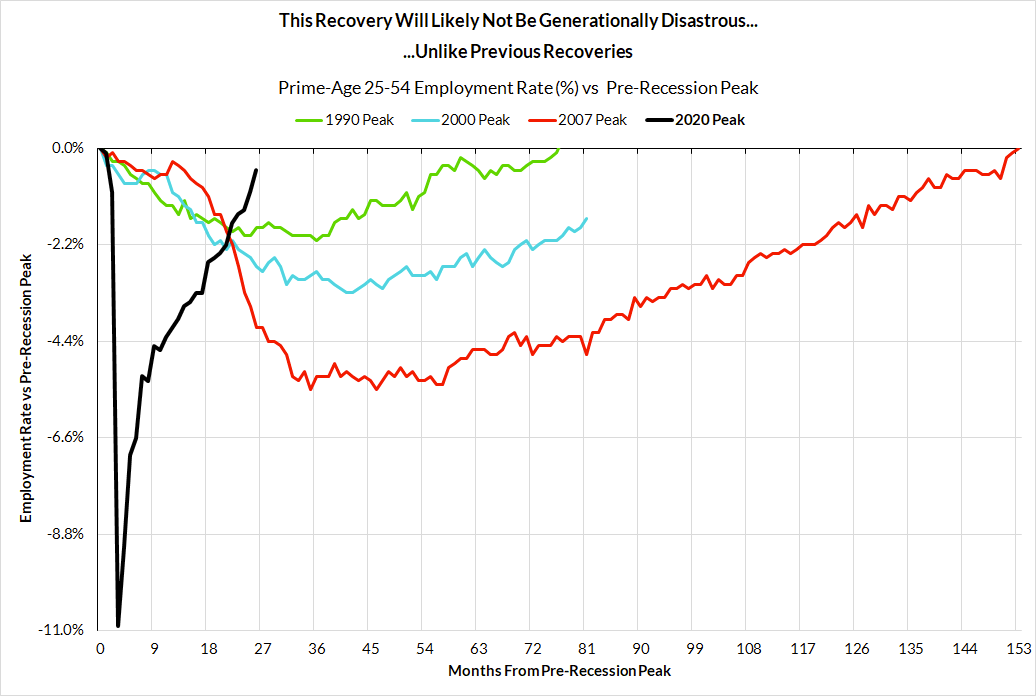

Today, most data indicate that the labor market recovery from the pandemic recession has been one of the most successful in American history. However, with the rolloff of fiscal support, the maturation of the reopening process, and further idiosyncratic supply shocks due to the war in Ukraine—as well as the still-ongoing pandemic—the recovery is liable to begin an endogenous cooling process.

While the inflation outlook remains locally strong, with risks to headline inflation tilted firmly to the upside in the near term, we should be beginning to see tangible signs of core inflation relief in the coming months. If you've been following our monthly inflation commentary, you will know that we had been flagging strong monthly inflation readings in Q4 and to start the year in January, but also a shifting back in the balance of risks to core (ex-food, ex-energy) inflation relative to the forecasting consensus, starting in February.

- Primarily due to the war in Ukraine, headline inflation risks printing to the upside relative to the 1.2% m/m consensus (1.3%-1.4% m/m), largely because of the effects of higher natural gas and agricultural commodity prices on electricity, utility gas service, and food at home.

- The risks to core inflation are beginning to turn to the downside more clearly relative to the elevated 0.5% m/m consensus (0.3%-0.4%). While private measures of used cars typically lead CPI-equivalent measures, we have seen some notable slowing over the past 10 weeks that should begin to more noticeably filter through. Of course, upside scenarios can still materialize, especially if rent and OER inflation could offset the used cars impulse in March. Downside core PCE risk should be stronger in April thanks to partial implementation of the Medicare sequester.

With the recovery beginning to slow of its own accord, it is critical that the Fed tailors monetary policy both to the uncertainty we see today and the likely trends in inflation over the medium term. With an endogenous slowdown in many sectors, the Fed's attempts to actively slow the economy further must be treated with care.

The labor market recovery since the pandemic recession has been incredibly successful, making a nearly complete recovery to pre-pandemic conditions, with the Prime-Age Employment rate at August 2019 levels.

As we have pointed out previously, our real-time GLI measure has likely recovered as of March; the Prime-Age Employment Rate is just 0.3% from the 2019Q4 level.

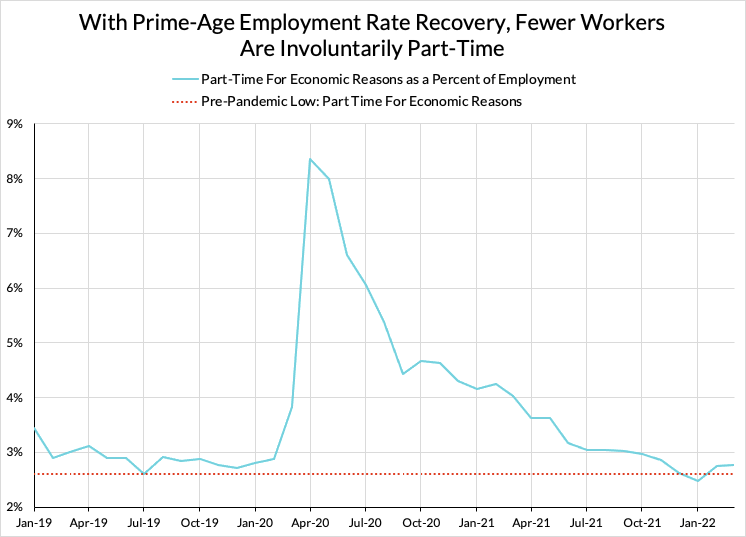

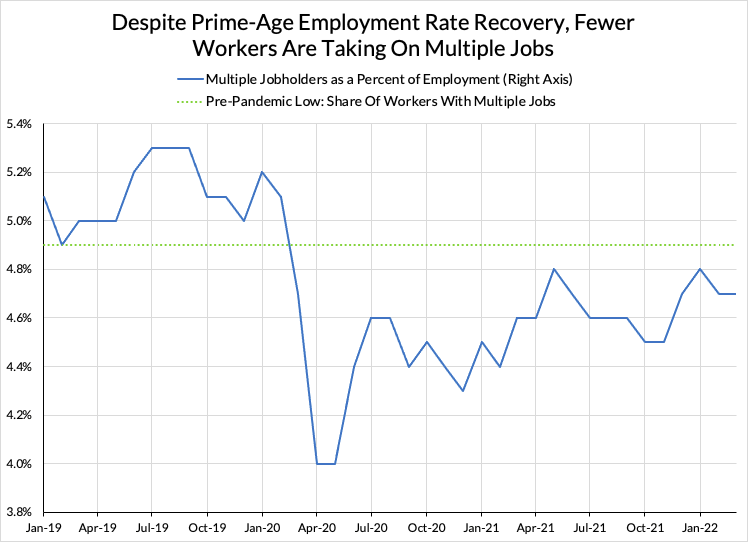

More idiosyncratic measures confirm this labor market strength: the share of workers who are part-time due to an inability to find full-time work has fallen below its pre-pandemic trough, while the share of workers holding multiple jobs has done the same.

Unrelated to labor market tightness, the headline inflation outlook remains locally strong given recent month-over-month strength in key components, and further upside risks lurk for headline inflation. Higher natural gas prices – driven in part by extreme price spikes in Europe and making new highs currently – will likely affect the measured price of utilities.

Russian oil and gas production may also go offline if discounting and inventory conditions force well shut-ins, while US oil production has not kept pace with global price increases.

The food price shock from the Ukraine war is harder to quantify, and will likely have differential effects based on the import intensity of food consumption in different countries. The US may be insulated from some of these price pressures, yet agricultural producers have already seen tremendous increases in specific Producer Price Index components since the beginning of the pandemic.

The effects of the war in Ukraine on European automobile supply chains are also hard to forecast exactly, but we can know for sure that further shelling will not improve global supply conditions.

China is also facing the worst moment for supply chain and pandemic management since early 2020. The marginal effect of shipping delays due to enhanced quarantine procedures is difficult to predict, but high-frequency data confirm that Beijing subway ridership has fallen below its levels during the initial round of lockdowns.

Yet despite all of these factors, we should begin to see signs of local inflation relief in coming months. For example, used car prices are beginning to cool now that rental car companies have largely rebuilt their fleets or have shifted to other sources of supply.

April will also see the medicare sequester going partially into effect, something we have identified as making a material contribution to lower medium-term inflation readings. Recent ISM Services and ISM Manufacturing reports have also loosely indicated a handoff from goods to services, suggesting that inflation – especially in durable goods – will likely moderate following the handoff.

With all this in mind, the Fed should be calibrating its tightening efforts to what current financial conditions are indicating. We saw across-the-board tightening headed into the March FOMC meeting that amplified the impacts of the 25bp hike. Since then we've seen more two-way volatility, especially as Fed communications have sometimes painted conflicting pictures of the near-term path of interest rate policy. The Fed is sounding increasingly convinced of the need for 50bp hikes (despite no new inflation information since they last met). A decision at the May FOMC meeting likely will not make or break the business cycle expansion, but it will be pivotal to stay nimble to changes in the data flow and financial conditions.

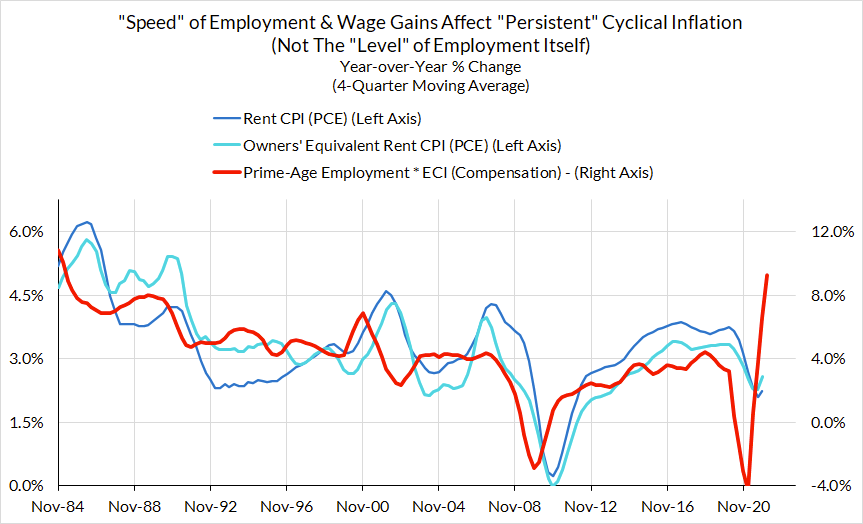

The rapid cyclical labor market recovery is likely to put some short-run upside risk on the most cyclical components of inflation, namely rent and owners' equivalent rent. But as the economy and labor market slow, so too will the outlook for these cyclical components of inflation (which tend to respond with a 12-18 month lag).

With the economy beginning to slow, and supply-side pressures potentially on the cusp of easing, the case for sharper rate hikes needs to be taken on a meeting-by-meeting basis. As the past two months have shown us – conditions can change rapidly. Consistent with our framework, strong nominal labor income growth and a strong local inflation outlook are reasonable grounds for slowing down the economy, but a slowdown is likely already underway. It's important that the slowdown not be so abrupt that it tips the economy into recession. With the labor market recovery proving to be sufficiently rapid and now reasonably secure, we are now transitioning into a new phase of this expansion. The Fed will need to take care in how they manage the coming slowdown—albeit from very high nominal and real growth rates—to a more noninflationary growth rate of labor income without catalyzing recessionary dynamics in the process.