As policymakers grapple with the challenge of achieving a soft landing, one underrated tool is reducing healthcare inflation. With healthcare costs projected to rise over the coming decade, a policy proposal that has been circulating is making Medicare reimbursements site-neutral. In this brief, we estimate the disinflation effects of implementing site-neutral payments for Medicare.

Introduction

With inflation declining over the course of 2023, the Federal Reserve is likely to begin cutting interest rates in 2024. While many economists predicted a recession by the end of 2023, the question now turns to whether we can stay on the “golden path” and achieve a soft landing.

This soft landing is far from guaranteed. Over the past year, the winding down of key inflationary factors like energy price spikes and supply chain snarls have contributed to the historic disinflation. However some commentators argue that the last percentage points of disinflation to the Fed’s target range could be the most difficult. If disinflation does not continue, the Fed could keep rates higher for longer, ultimately hurting supply-side investment and introducing new inflation risks. There’s also a risk of reacceleration or geopolitical challenges that could lead to new price shocks for global commodities. In just the past few weeks, attacks in the Red Sea have forced shippers to reroute around the Cape of Good Hope, increasing the cost of shipping goods. Although impacts have largely been confined to Europe and China, the global nature of logistics markets may propagate these price shocks. Other risks could materialize into broad-based or sectoral inflation, like a shortage of transformers or a supercycle bottom in a key raw materials. Congress can improve this uncertain outlook by pursuing a policy that helps the soft landing by securing disinflation in areas where federal authority is strongest.

The federal government has significant power to bring down healthcare prices, as we’ve written in the past. Past research has demonstrated that Medicare cost reforms in the Affordable Care Act contributed to the persistently weak inflation in the mid 2010s. While healthcare costs are projected to rise over the coming decade, there are plenty of sensible reforms that could bend the cost curve. One big change is already happening—in 2025, pharmaceutical prices will come down as the federal government implements the first year of negotiated pricing. And Congress is in the red zone for another: applying site neutrality to Medicare payments. In a bipartisan vote, the House recently passed the “Lower Costs, More Transparency Act,” which would reduce the costs for drugs administered by providers. If wider site neutrality reforms were adopted, Congress could reasonably reduce the core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index (the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation) by 15 to 32 basis points over the coming year to two years, depending on the level of passthrough from Medicare rates to private prices.

With a soft landing in sight, policymakers should move decisively to secure and sustain it. Every basis point matters, and this important reform is close to becoming law. Congress should pass the Lower Costs, More Transparency Act immediately and pursue broader site neutrality reforms.

Analysis

After reaching record highs during the pandemic, healthcare spending has declined as utilization returns to pre-pandemic levels. However, the recent decline is not expected to last. The annual growth rate for healthcare spending for 2023 is expected to exceed the annual growth rate of GDP, and should this trend continue, some analyses estimate that total healthcare expenditures could comprise nearly 20% of United States economic output by 2031, reaching the historic highs experienced during the once-in-a-century pandemic that pushed our healthcare system to the brink.

One sensible solution to contain the upward trajectory of healthcare costs is to implement site-neutral Medicare reimbursement payments. Medicare currently reimburses outpatient services performed at healthcare institutions like Hospital Outpatient Departments (HOPDs) at higher rates than stand-alone physician offices, even if there are no discernable safety benefits or gains in quality of care.

Medicare’s Payment Structure Compensates Differently for Services Even When There Is No Value Add

Medicare Part B covers outpatient services, physician services, and physician-administered drugs, and makes up 48% of total Medicare spending. However, not all outpatient services are treated the same. Services performed at hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) or ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) are priced significantly higher than the same services performed in a physician’s office.

HOPDs and ASCs are administered through two payment systems: (1) through the Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) and (2) through a second payment system, the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) (See Note 1). Physicians in private offices are reimbursed only through the PFS, but at a higher “non-facility” rate to cover the costs “related to running a private practice, including labor, resources, and capital costs.” Why is there an additional processing system for HOPDs and ASCs? The OPPS is intended to “cover additional services provided by these facilities such as “nursing services, medical supplies, equipment, and rooms.” While this may be reasonable in certain circumstances, there are many instances where Medicare is reimbursing for the additional services, even if they do not drive any improvement in care. The higher costs can be substantial.

For a typical clinic visit in 2017, a private physician could only seek reimbursement from Medicare through the PFS, and they would’ve been paid at a “non-facility” rate of $109.46. For the same service, an HOPD would receive a “facility rate” payment through the PFS of $77.88, plus an additional $106.56 payment through the OPPS–totaling $184.44, approximately 68% higher. In a 2023 study, Wakely analysts found that for outpatient medical services (also known as ambulatory payment classification codes or APCs), total reimbursement rates for HOPDs were usually 1.5 to 4 times higher than for private physician offices.

This problem also pervades the private insurance market. Reviewing national PPO commercial claims for six medical services from 2017 to 2022, BCBS found that total allowed costs for these services were significantly higher when performed in HOPDs or ASCs. For instance, the total allowed costs for a colonoscopy screening in 2022 were $1,224 at HOPDs, $925 at ASCs, and $611 at a physician's office. The total costs for colonoscopy screenings increased by 18% from 2017-2022 in HOPDs, while total costs only increased 8% in ASCs and even declined by 3% for screenings in an office.

With HOPDs receiving higher payments for the same services from the federal government and the private market, there is a financial incentive for HOPDs to purchase private physician’s offices and reclassify them as HOPDs to receive reimbursements at a higher rate, all while capturing a larger portion of the market. Essentially, they are “buying doctors,” and even though the location of the service is not physically changing, they are reimbursed at a higher rate. As a result of this consolidation, more than half of all physicians work out of hospitals, a substantial increase compared to only 26% of physicians employed by hospitals in 2012. With no reform to the current reimbursement system, this trend of consolidation is expected to continue, which will ultimately drive costs up further. Commenting on site-neutrality reform, the Association of Independent Doctors stated:

“Hospitals become more profitable when they employ doctors not only because they get paid more but because buying doctors expands the hospital market share, which allows hospitals to negotiate higher reimbursements from all payers, including Medicare which contributes to the upward cost spiral.”

As hospitals gain a larger market share, physicians are left with lower pay, as the higher reimbursements are channeled directly to the hospitals. Furthermore, the higher cost for the same services forces beneficiaries, who have a 20% cost share, to have unnecessarily high out-of-pocket costs without receiving better quality of care (See Note 2).

To counter the inequitable payment structure that favors hospitals and HOPDs, site-neutral payments aim to standardize reimbursement rates across different healthcare settings and promote fair compensation for all medical services to contribute to a more efficient and equitable healthcare system.

Congress Has Previously Passed Site Neutrality Reforms

Congress first passed site-neutral payment reform in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015. Section 603 of the Act targeted payment differences between HOPDs and physician offices. Under this legislation, newly established off-campus HOPDs were mandated to receive payment for services at the PFS non-facility rate instead of the OPPS rate. However, the legislation exempted off-campus HOPDs that were already established and operating under the OPPS, allowing them to continue to receive higher reimbursement rates. Consequently, when the legislation passed, most off-campus HOPDs were exempt from receiving the PFS rates.

In 2019, CMS implemented new regulations that essentially required all off-campus HOPDs to adopt site-neutral payments for regular clinic visits (evaluation and management). CMS faced a lawsuit against the rule, but on appeal, the DC District Court ruled that section 603 does not prevent CMS from adopting service-specific, non-budget-neutral rate cuts as a “method for controlling unnecessary increases in the volume of covered outpatient services.” Despite the steps Congress and CMS have taken to propel site-neutral payment reform, further progress remains. . CBO estimated that Medicare reimbursement rates to HOPDs would increase more than any other traditional Medicare benefits, resulting in a 100% increase from 2020 to 2030.

When an independent physician has the skillset and the resources to perform the same services at HOPDs for a fraction of the costs, there is no reason to waste taxpayer dollars and increase healthcare costs for Medicare beneficiaries. Site-neutral payments are a common-sense policy solution that has a broad coalition of supporters. Despite the pushback from the hospital industry, there has been momentum in Congress to support site-neutral payments for Medicare reimbursements. Many proposals have been introduced in the House and Senate this year, and as Congress weighs which legislative proposal it will pursue, a key benefit of site-neutral reform would be a reduction in inflation.

Medicare Payment Site Neutrality Would Support Disinflation

Healthcare costs are a significant portion of core PCE inflation, the Fed’s preferred measure. The PCE basket includes not only purchases by households but also purchases on behalf of households by third parties. This includes healthcare purchases made by public and private health insurance programs. With healthcare expenditures playing a significant role in the PCE basket, reforms like site-neutral payments can have meaningful impacts on the overall rate of inflation.

Site-neutral payments would have two main impacts on PCE inflation. First, there is the direct effect of Medicare reimbursement rates on the price index. Second, there is an indirect effect: previous research has shown changes in medicare reimbursement rates have a “passthrough” effect on private reimbursement rates. Therefore, while site-neutral payments directly reduce the prices paid by Medicare, there is an indirect effect on prices in the commercial market as well.

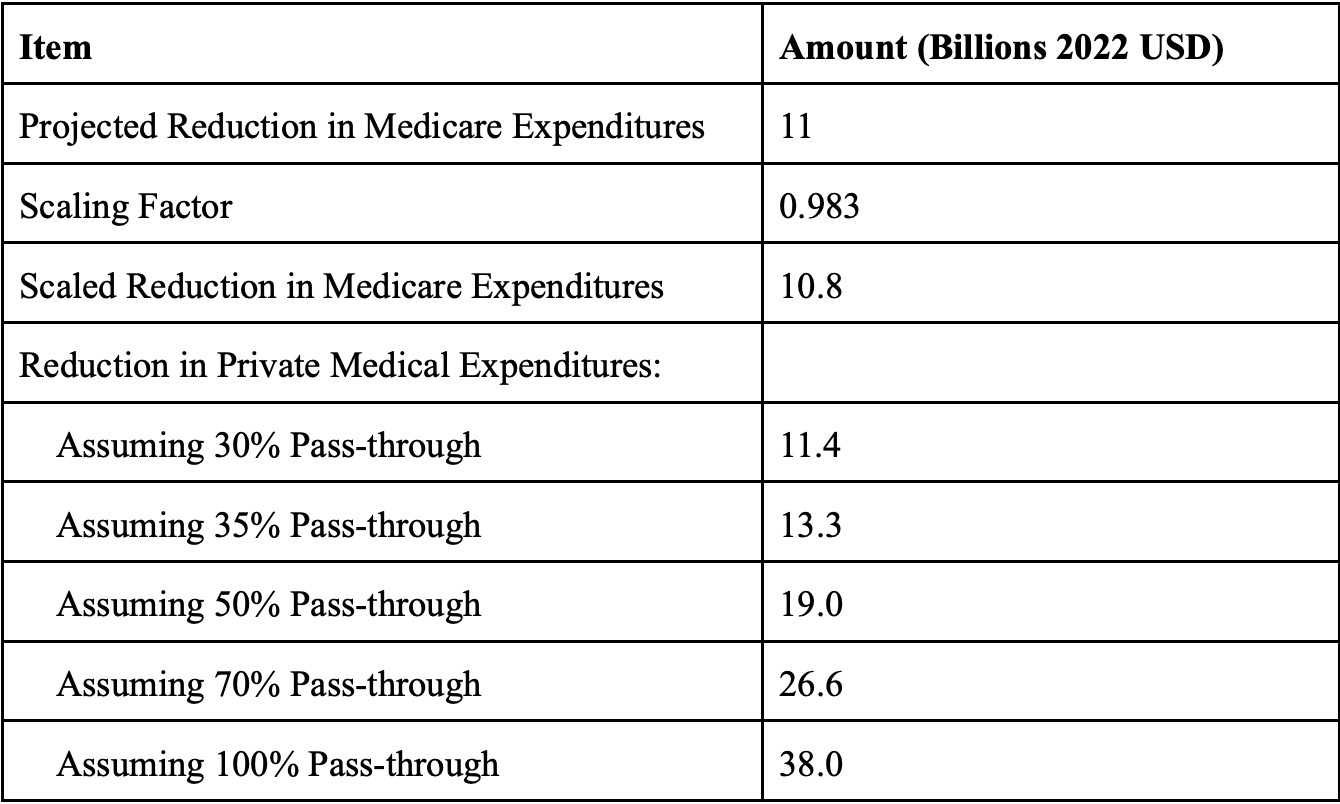

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) used MedPac’s 2014 policy recommendation to estimate the reduction in Medicare and private medical spending that would result from the implementation of Medicare site-neutral payments. MedPac’s recommendation to Congress was to implement site-neutral reform for 57 hospital outpatient services (APCs). MedPac chose these services to focus on APCs that were predominantly performed at a physician's office and with very little patient severity to ensure the services were comparable at each site.

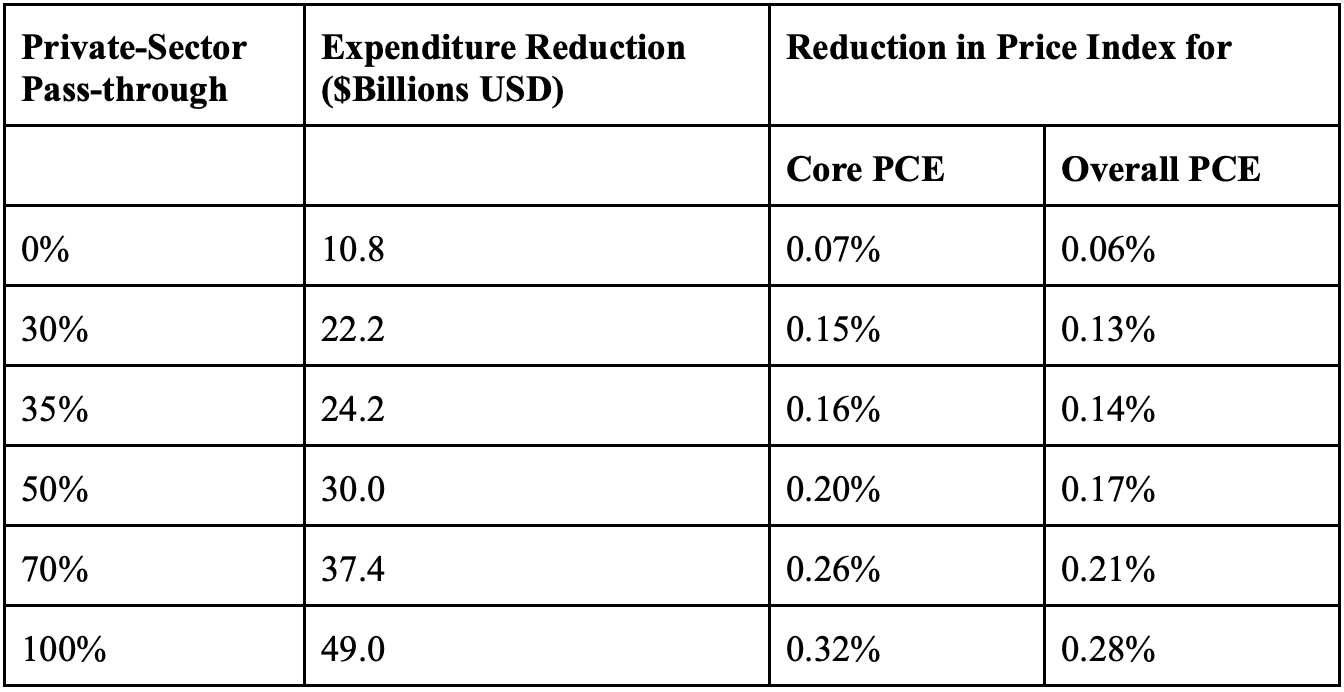

We take CRFB’s estimates of the effects of MedPac’s policy on reimbursement rates and use them to estimate how site-neutral payments would have affected the core PCE price index if implemented in 2022. The Appendix outlines how we found the reduction in healthcare expenditures and scaled CRFB’s estimates. Given the uncertainty around the extent of private-sector pass-through, we report the estimated reduction in the PCE price index assuming a range of pass-through rates to private-sector prices between 30% and 100%. It is important to note that private-sector pass-through happens gradually, so the total effect on inflation from the indirect private-sector effects would be felt in the years after the implementation of site-neutral payments.

We estimate that the direct effect of site-neutral payments on the overall core PCE price index is a reduction of 7 basis points. The total effect on the core PCE price index, including private-sector pass-through effects, is between 15 and 32 basis points, depending on the extent of private-sector pass-through. Assuming the direct effect occurs in the first year, and a 35% pass-through indirect effect occurs in the second year (consistent with prior research on the pass-through from Medicare reimbursements to private prices), this would result in a 7 bps and a 9 bps reduction in core PCE inflation in each year, respectively.

To contextualize this magnitude, the 12-month core PCE growth rate in November 2023 was 3.16%, a 116 basis points overshoot over the Fed’s 2% target. The Fed’s current Summary of Economic Projections sees core PCE inflation ending in 2024 at 2.4% and 2025 at 2.2%; implementing site-neutral payments in 2024 would reduce 17.5% of the projected inflation overshoot in 2024 and 45% of the projected overshoot in 2025.

Reduction in Healthcare Expenditures

Reduction in PCE Price Index

Conclusion

Site-neutral payments have the potential to save the federal government between $217 and $279 billion over a decade, lower out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries, reduce national health expenditures and meaningfully reduce core PCE inflation while supporting lower interest rates within the bounds of the Fed’s mandate.

The House recently passed one of the many site-neutral payment bills discussed over the course of last year, the Lower Costs, More Transparency Act, which is also included in a bipartisan bill introduced by Senators Mike Braun and Maggie Hassan . The legislation equalizes Medicare reimbursement rates for drugs administered at off-campus HOPDs with private physician offices and ASCs. The legislation is estimated to reduce reimbursements to hospitals by almost $4 billion over a decade. While this might not have large disinflationary effects on the economy, in our quest to secure a soft landing, every basis point counts. Congress and the Administration should continue to pass site-neutral payment reforms for healthcare services that can be performed at the same level of care, whether the services are performed at hospitals, physician offices, or ASCs.

Appendix

The core PCE price index is a Fisher-ideal price index, which is a geometric average of Laspeyres and Paasche Price indices. Laspeyre and Paasche price indices are both fixed-quantity price indices, which measure the change in the cost of purchasing a fixed basket of goods. Since the CRFB methodology assumes fixed quantities, the overall PCE price index reduction is well-approximated by the percent reduction in overall nominal personal consumption expenditures resulting from implementing site-neutral payments.

CRFB estimates the dollar reduction in health expenditures by Medicare and the private sector over a ten-year period (2021-2030) relative to the forecasted Medicare spending from the 2020 CBO baseline and private spending from the 2020 CMS NHE projections. The reduction in Medicare expenditures is estimated under the assumption that the underlying basket of Medicare expenditures is unchanged by the move to site-neutral payments; that is, the expenditure reduction arises from a reduction in prices alone. CRFB reports a range of estimates of the reduction in private sector expenditures, assuming different levels of pass-through from Medicare reimbursement rates to private sector reimbursement rates.

CRFB’s projections were based on pre-Covid Medicare expenditures from the 2020 CBO baseline. Since actual Medicare expenditures were different from the baseline projection, we scaled the expenditure reduction by the difference between actual and realized Medicare Part B Expenditures. Medicare Part B Outlays in 2022 were $466 Billion, versus the expected outlays for 2022 in the baseline of $474 Billion. To scale the reduction, we divide the actual Medicare expenditures by the estimated baseline ($466 / $474 =0.983).

Likewise, we scale the reduction in private savings by the difference in realized between actual and projected expenditures on physician and clinic services funded by out-of-pocket payments and private health insurance in the CMS National Health Expenditures data. Private expenditures on physician and clinic services were $407.7 Billion in 2022; the projection from the CMS March 2022 was $409.3 Billion. We scale the reduction in private savings by 409.3/407.4 = 1.004.

As CRFB notes, there is considerable uncertainty about the effect of implementing site-neutral Medicare payments on private reimbursement rates. Previous research shows that a reduction in Medicare reimbursement rates in the context of surgical procedures led to reductions in private reimbursement rates. The reduction in private sector reimbursement rates takes place over time, with a 1% reduction in the Medicare reimbursement rate leading to a 0.35% reduction in private rates within two years and a 0.70% reduction in the long-term.

Notes

Note 1: The ASC payment is its own system, separate from the OPPS, but is primarily linked to the OPPS. There is a separate conversion factor that determines total ASC payment and it reduces the reimbursement to ASC compared ot HOPDs by a little more than half, but still results in higher payments to ASCs when compared to private physicians’ offices. The 2023 ASC conversion factor was 61 percent of the OPPS conversion factor.

Note 2: In fact, a recent study found that patients receiving gastrological services after vertical integration receive worse care and have an increase in post procedural complications. One of the researchers, Soroush Saghafian, a Harvard Professor who studies healthcare operations and management stated: “Vertical integration is leading doctors to change the way they approach patient care, with consequent adverse effects on patient health, and is also inflating costs.”