The September 2023 labor market data continued to show a strong labor market.

The headline unemployment rate remained steady at 3.8%, and the establishment survey showed an eye-popping 336,000 jobs added in September—alongside an upwards revision of 79,000 and 40,000 jobs in July and August. There was little change in the household survey measures of employment, with prime-age employment for both men and women holding steady and prime-age participation holding steady. While we should never take too much away from one month’s average hourly earnings numbers, September’s wage growth was especially soft. Average hourly earnings for both all private workers and production workers came in at just 2.5% annualized.

Three highlights from this month:

- Slowing But Strong: This month’s data is a continuation of our “slowing, but strong” description (formerly “strong, but slowing”). Employment levels are healthy but overall the trend is towards slowing.

- Catch-Up Job Growth: This month’s jobs in the establishment survey are primarily coming from sectors that have underperformed during the labor market recovery: leisure and hospitality, health care, and government.

- Wage Growth is Slow: Wage growth continues its downwards trend. Quarterly wage growth is just above 4.0%, and the Fed should see this level of wage growth as consistent with its inflation mandate.

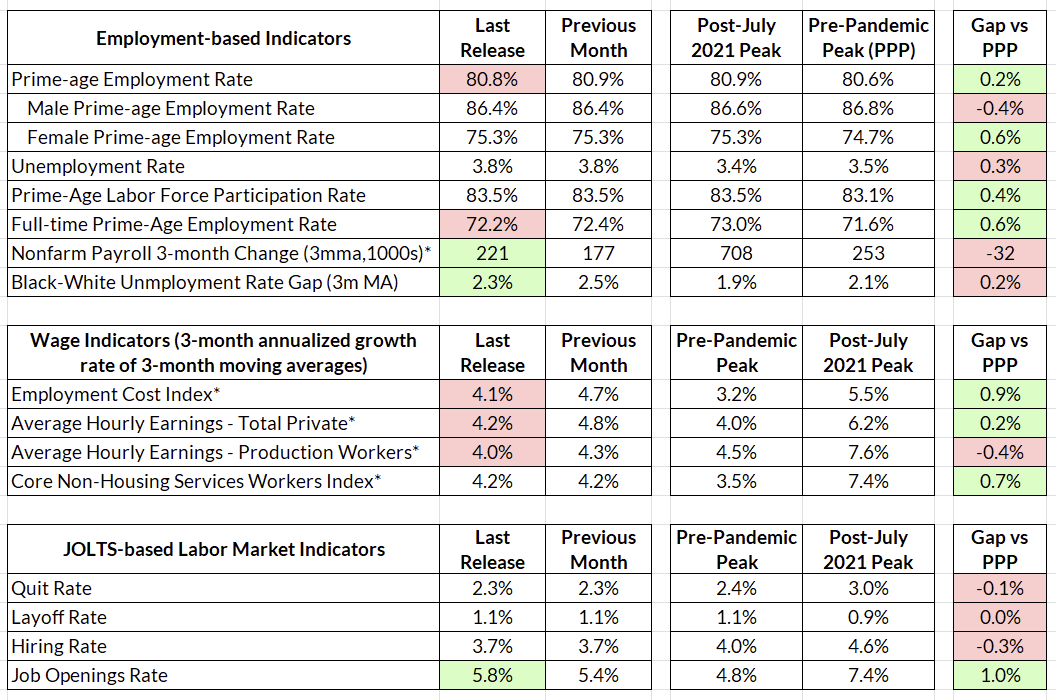

Labor Market Dashboard: September 2023

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Author’s Calculations. Red indicates weaker labor market development; green indicates stronger.

*Previous month figures for these indicators refer to the as-reported numbers from the previous month, not the previous month’s figure in the current vintage. For an explanation of why, see this post.

Still Strong, but Slowing in the Household Survey

The headlines will surely be dominated by the large increase in employment from the establishment survey. However, the household survey is less sanguine. It appears that our favorite labor market indicator, the prime-age employment rate, is plateauing. After three straight months at 80.9%, the prime-age employment rate ticked down to 80.8% in September. The prime-age labor force participation rate and the overall unemployment rate were unchanged from August.

Likewise, gains in full-time employment have also essentially leveled off:

Looking into the finer details of the household survey, there isn’t any cause for alarm about the labor market in the September data. Things essentially look the same as the last few months, with no meaningful changes in the number of short-term unemployed, the number of permanent job losers, and the number of workers that are part-time for economic reasons. The one notable trend I haven’t yet commented on is that labor market reentrants seem to be on the rise, once again providing evidence that a strong labor market can pull people in from the sidelines.

About that Payrolls Number

The big number from today is the 336,000 jobs added in the establishment survey. Another eye-popping fact about today’s employment numbers is that this is a large increase on top of upwards revisions to previous months. Employment was revised upwards by 79,000 and 40,000 jobs in July and August, respectively.

It turns out, all of those revisions are attributable to government jobs. While the last release showed almost no jobs created in government in July and August, those numbers have been revised to show a substantial increase in government jobs.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

This month saw another large increase in government jobs, mostly coming from state and local government employment. Looking more broadly at the source of employment gains this month, it looks like the labor market is continuing its sectoral renormalization I highlighted in May’s recap, in that recent job growth is stronger in sectors that have recovered the last from the pandemic.

Have Wages Slowed Enough?

This month saw another soft print of average hourly earnings. Average hourly earnings for both production workers and all private workers grew at just 2.5% in September, a post-pandemic low (except for an aberrant 0% print for private workers in February 2022). This is, of course, a print from a number that will get revised (and may be subject to some composition effects due to job growth in lower-earning sectors). The Fed will get Employment Cost Index data on the first day of their next FOMC meeting at the end of this month, so the committee will have some higher-quality data then. However, what we can say with the available data so far is that overall the trajectory of wage growth is towards slowing.

The quarterly growth rates of private and production workers’ average hourly earnings are now running at 4.2% and 4.0%, respectively. The decline in wage growth for production workers is especially notable—wage growth was running at 5.3% for these workers just a year ago.

What does this mean for the Fed? In the past, Powell has alluded to the concept of “wage growth consistent with inflation”, suggesting that wage growth should be approximately equivalent to inflation plus productivity growth. He’s even indicated a specific number, 3.5%, as a reasonable level of wage growth, implying labor productivity growth of 1.5%.

With that productivity number, we are not too far from wage growth being where Powell wants it to be. But, looking at Q3 forecasts of GDP and a relatively small growth rate in hours, productivity growth could very well be within the range of 2.0% to 3.5% in Q3 2023. By Powell’s own framework, wage growth is on the lower end of what’s consistent with 2% inflation. Given the Fed’s proclivity for thinking about wages as contributing to inflation in a cost-push channel, the Fed’s job on the labor market is done, at least according to this metric. In short, the combination of slowing wages, slowing hours growth, and an increase in GDP growth means the Fed can no longer claim that wage growth is too high.

Policy Risks and Implications

In one sense, the labor market story from this month is just the next step in the “strong, but slowing” narrative we’ve seen in the economy over the past year. In terms of household employment numbers, little has changed from last month. Wage growth slowed a little. Sectoral employment growth is marginally reversing some of the changes from the pandemic.

However, over the last few months these evolutions have moved the labor market to the point where the Fed should consider the idea that they have the labor market where they want it. Household employment gains have slowed to the point where they’ve effectively plateaued. Wage growth has slowed to the point where, when taken along with recent productivity improvements, it should be considered to be consistent with the Fed’s inflation target. Quit and hiring rates are at 2019 levels. At this point, the only indicator out of step with this narrative is the job openings to unemployment ratio, which at this point has proven to be an unreliable guide to inflation.

Considering the recent favorable inflation trajectory, the balance of risks between inflation and unemployment are now swinging more strongly towards unemployment. And while the Fed might talk tough, it seems that they are at least starting to move in that direction (at the last press conference, Powell indicated that the risks will become “more two-sided” as rates approach their plateau). What remains to be seen is how the inflation trajectory evolves and how hard headwinds—higher long rates, resumption of student loan payments, a potential government shutdown, and the end of childcare support—hit the economy and the labor market. We’re not out of the woods yet.