Contrary to the expectations of Fed officials, labor force participation growth has been strong over the last six months. In this piece, I use Current Population Survey microdata, correct for measurement issues, and show that an increase in labor force entry played a significant role in this recent development, with labor force entry rates above pre-pandemic levels. Given time, a robust labor market brings in workers from the sidelines, and labor force participation may still have room to grow beyond pre-pandemic levels.

For months, Fed officials have frequently said that one reason inflation is high is that “labor demand substantially exceeds the supply of available workers.” They frequently cite the high ratio of job openings to unemployed workers as evidence of this imbalance. This view of the labor market is why they think the unemployment rate needs to rise; Daly recently said that it would be "completely reasonable" for the unemployment rate to rise to 4.5%, an increase that is not seen without recessions.

Until recently, the Fed has been downplaying the possibility that the supply of workers may come about through improved labor supply. For months, much ado has been made about “missing workers” (even though the shortfall in labor force participation is almost entirely accounted for by workers above the age of 70, many of whom were working part-time jobs).

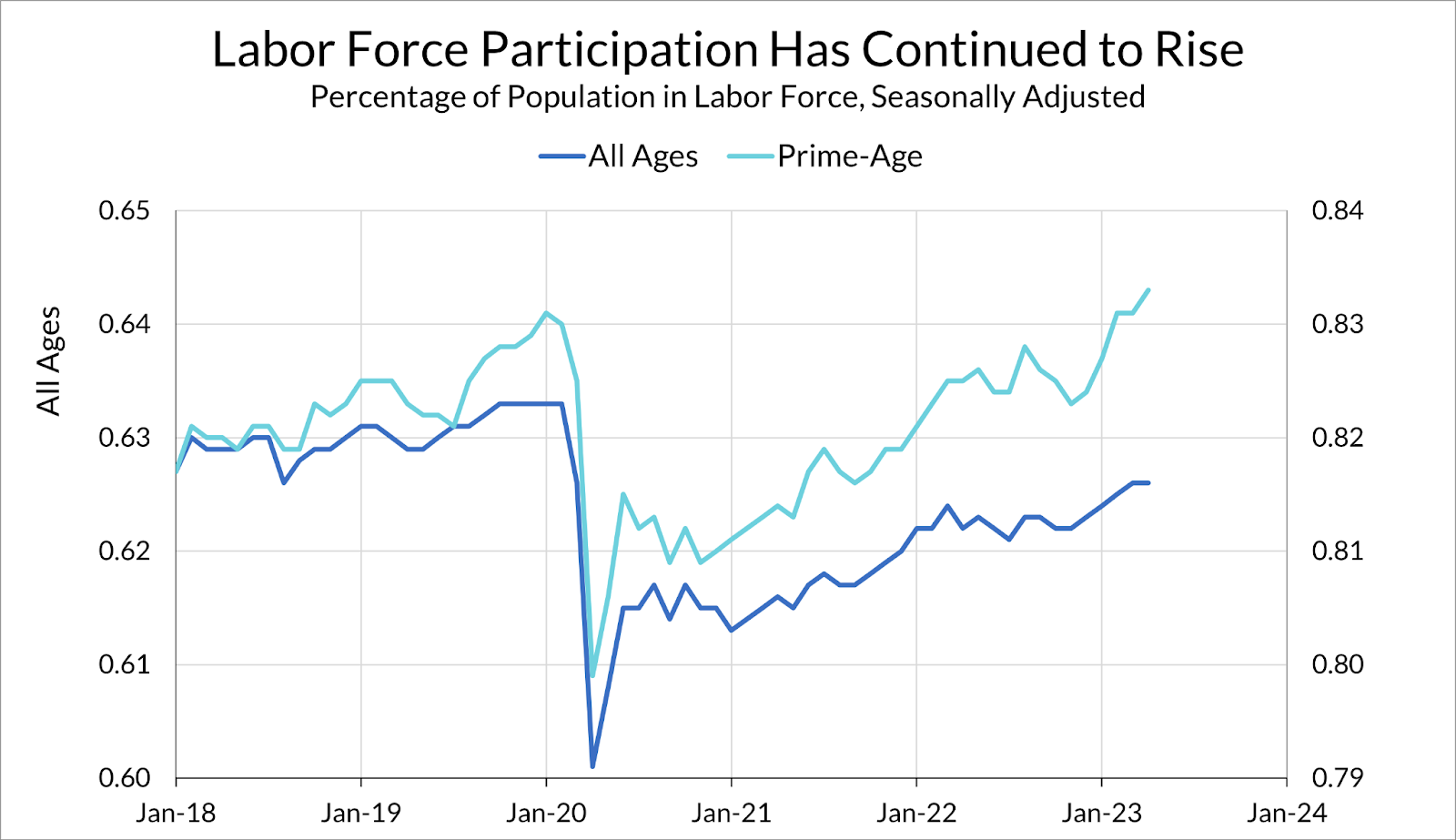

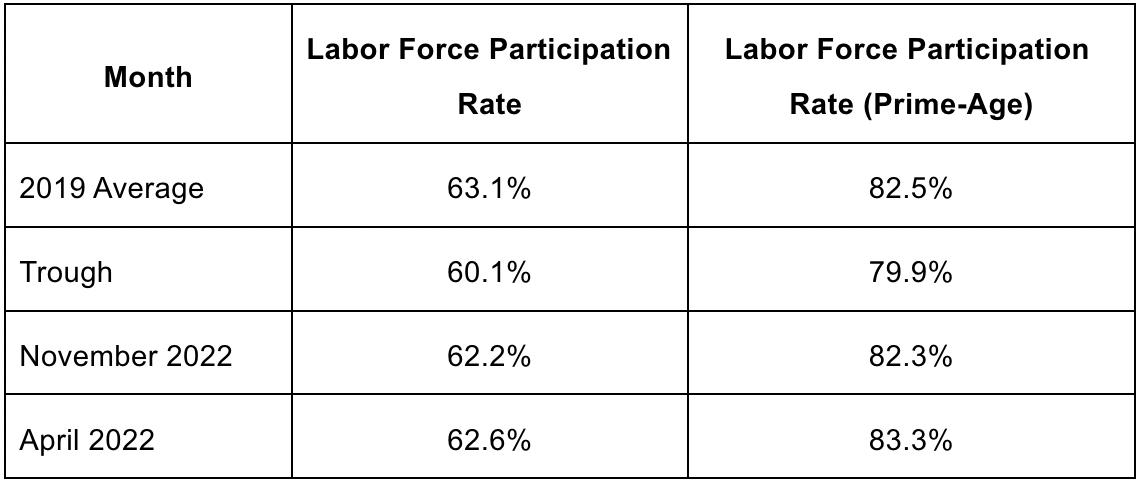

At the November 2022 FOMC press conference, Chair Powell said of the labor market, “we’re getting really nothing in labor supply now.” At the time of his statement, progress in labor force participation appeared to be stalling. Since then, however, participation has increased rapidly since then, particularly among prime-age (25 - 54) workers. In the last six months, Labor force participation rates rose 0.4% and 1.0% for the whole population and prime-age workers respectively. Prime-age labor force participation has now surpassed its pre-pandemic peak.

What accounts for the recent uptick in labor force participation? In this report, I examine month-to-month flows in the Current Population Survey (CPS) microdata to account for this recent trend in terms of entry and exit rates to and from the labor force. I account for labor force status misreporting and time aggregation bias to calculate hazard flow rates in and out of the labor force.

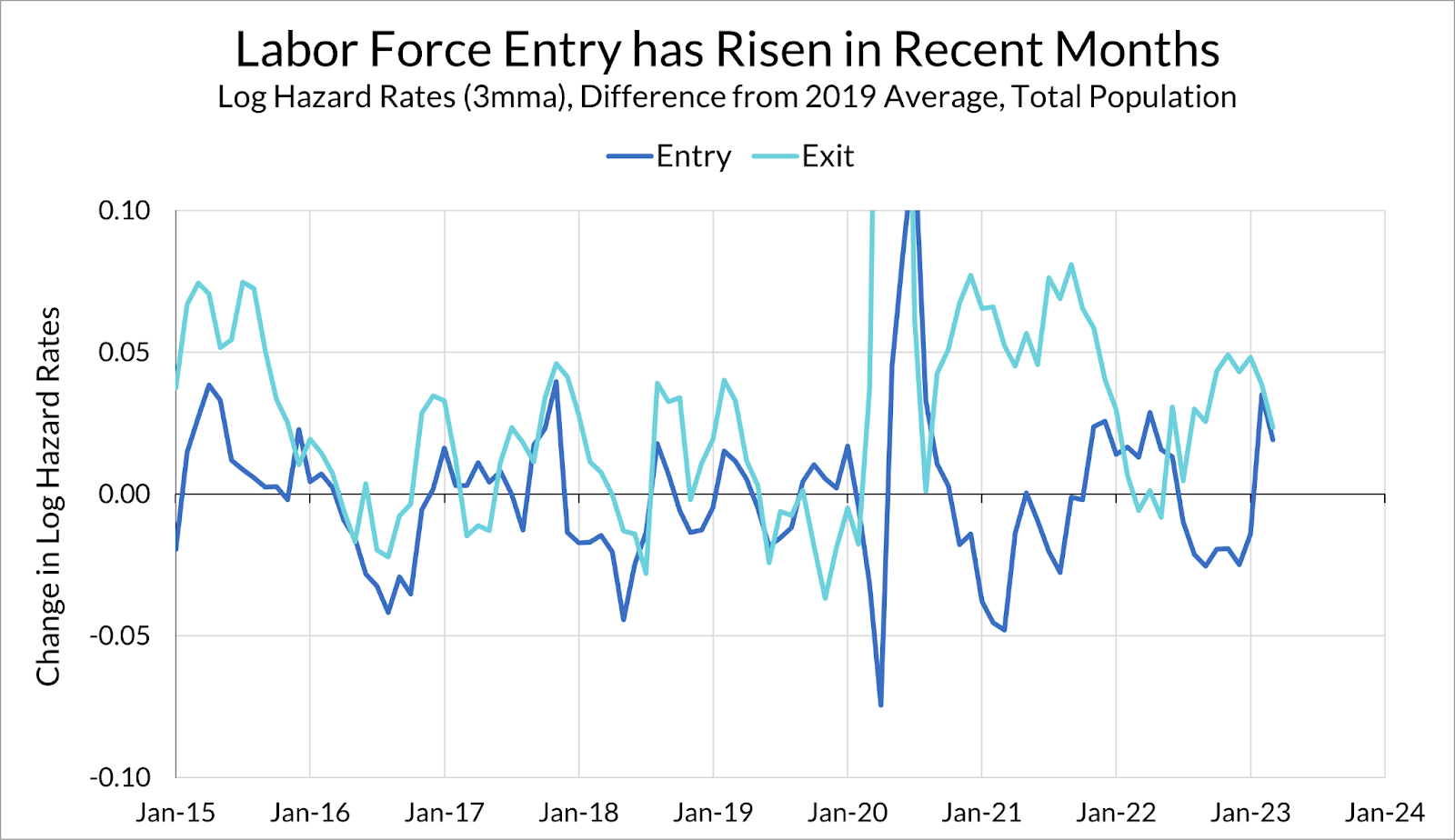

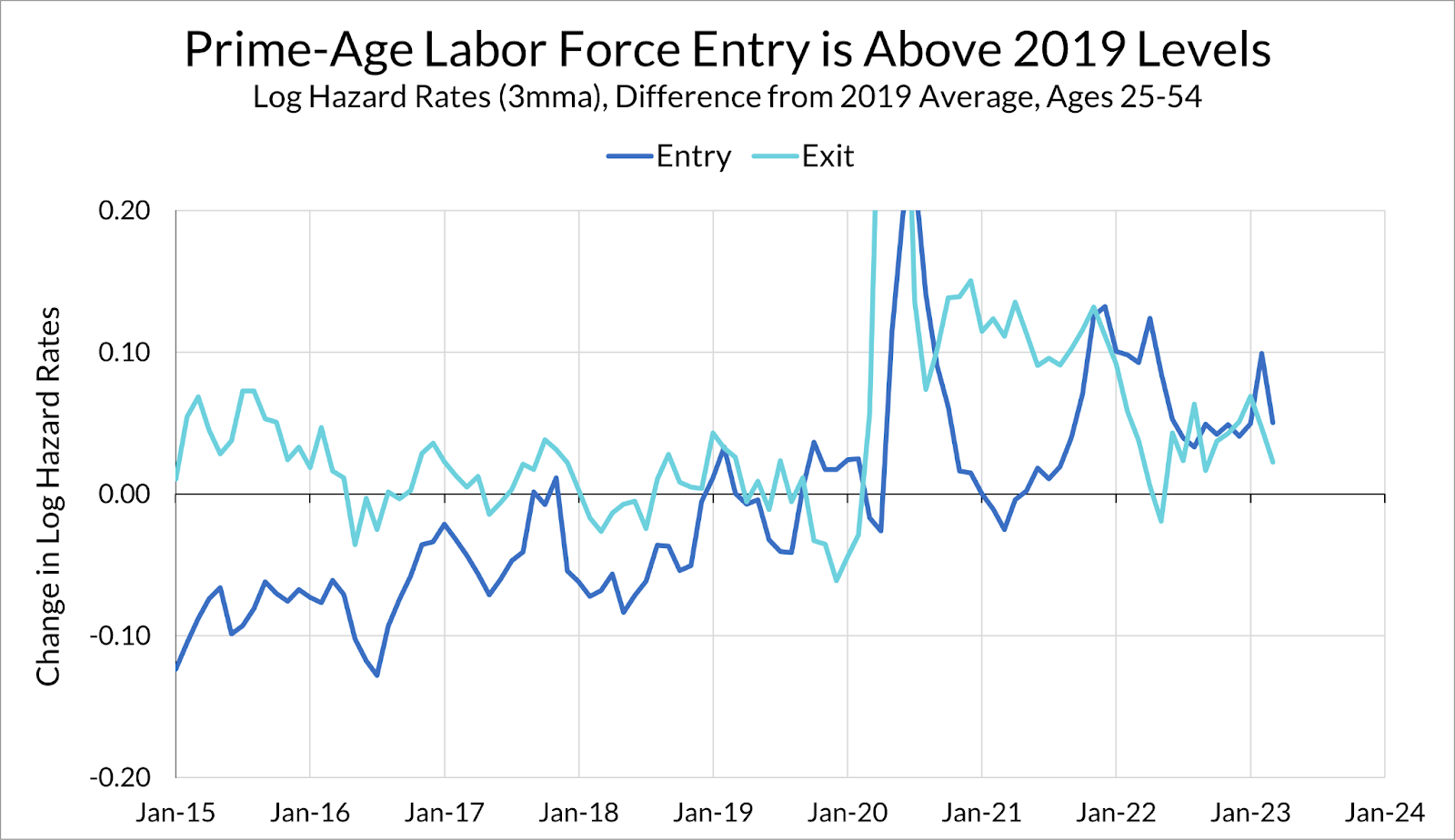

I find that both inflows and outflows to and from the labor force play a significant role in the recent increase in labor force participation, both in the prime-age and overall population. For the whole population, labor force entry rates were depressed (relative to 2019 levels) throughout much of 2022 but have increased in recent months. Meanwhile, entry rates among the prime-age population slowed to 2019 levels earlier in 2022 but are now substantially above their 2019 levels. Turning to labor force exits, outflow rates for both the overall population and the prime-age were elevated in 2022 but have fallen in recent months.

The uptick in labor force participation in recent months appears to be due to both an increase in labor force entry and a decrease in labor force exit. If these patterns continue, worries about “missing workers” may turn out to be premature. Given enough time and a hot labor market, labor force participation may continue to rise.

The Ins and Outs of Labor Force Participation

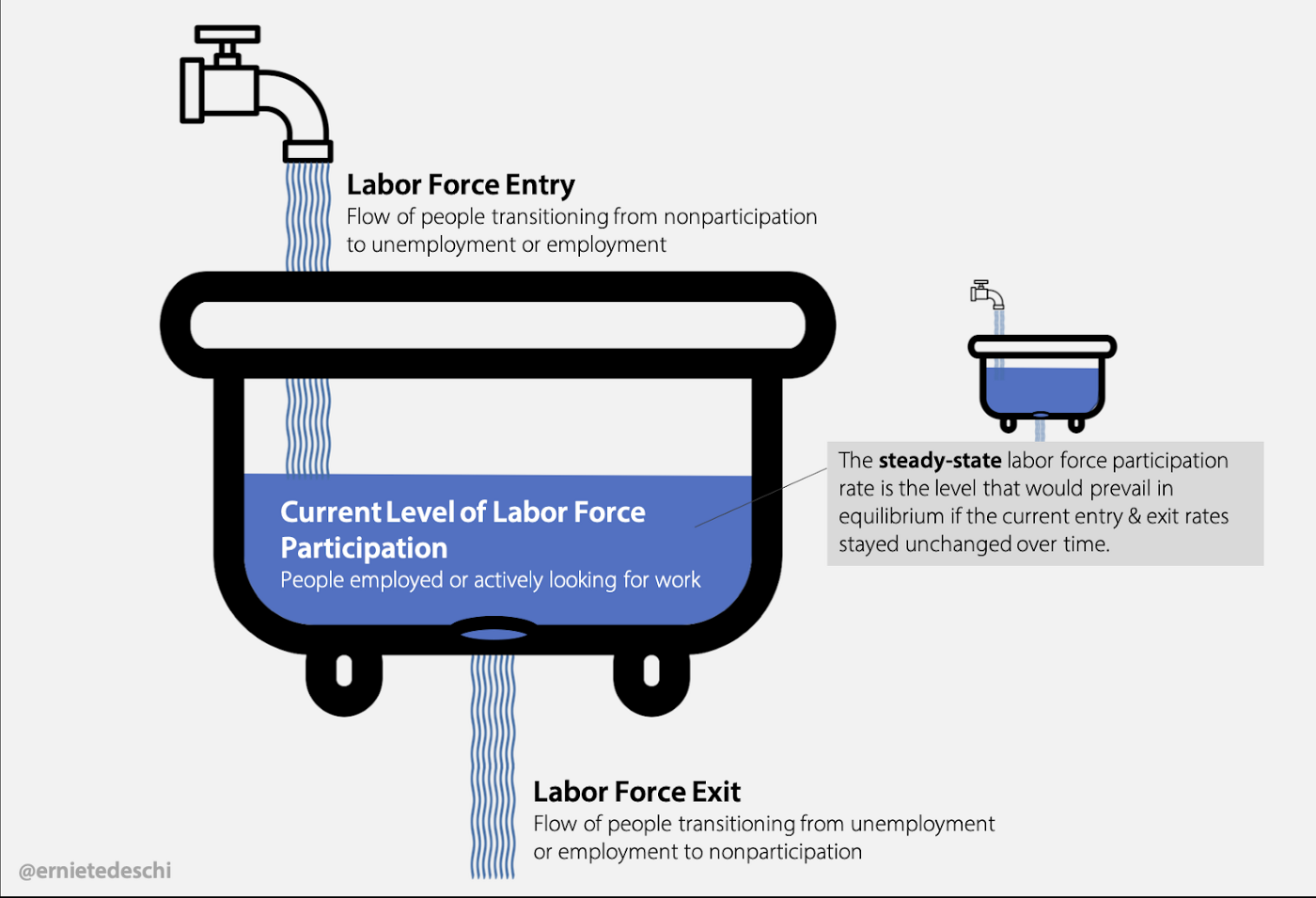

In “Participation and the Hot Labor Market”, Ernie Tedeschi described the labor force using a “bathtub” model. In this model, as in real life, people are moving both into and out of the labor force. As with the water in a bathtub, the labor force level is determined by both the inflow (entry) and outflow (exit) rate to and from the labor force. Labor force participation can thus rise through either an increase in inflows, a decrease in outflows, or a combination of the two.

As with Ernie Tedeschi’s earlier work, I use the limited repeated-panel nature of the CPS to track worker flows across months as well as adjust their labor force status responses to account for classification errors. In the CPS, respondents sometimes report switching between nonparticipation one month, unemployment the next month, and nonparticipation again in the third month. Others report being out of the labor force one month, and then report being unemployed for more than five weeks the next month. I adjust the CPS responses to correct for these inconsistencies using the methods from Elsby, Hobijn, and Şahin (2015) and Ahn & Hamilton (2019). Tedeschi showed that these corrections had a large effect on the measured entry and exit flow rates after the Great Recession.

In addition, I also seasonally adjust these month-to-month flow probabilities and also convert them into instantaneous hazard flow rates using methods from Shimer (2012). Doing so helps account for “time aggregation bias”, which arises from only being able to observe households once a month, rather than continuously.

Using an analogous argument from Elsby, Michaels and Solon (2009), one can approximate the change in the labor force participation rate as proportional to the difference in the changes in the logged labor force entry and exit hazard rates. Below, I graph the difference in the logged 3-month moving average labor force entry and exit hazard rates from their 2019 average levels.

Labor Force Entry is Picking Up

The evolution of entry and exit over the course of the pandemic recession and recovery explain the failure of overall labor force participation to return to its pre-pandemic levels. After the initial shock of the pandemic, the labor force exit rate remained elevated even throughout 2021, and labor force entry rate never rose much above 2019 levels. However, in recent months, the labor force entry rate has picked up sharply and the exit rate has fallen somewhat, leading to the rise in the overall labor force participation rate. In log terms, both entry and exit rates are at similar levels relative to 2019; if current trends continue, overall labor force participation could return to pre-pandemic levels.

Turning to prime-age workers alone, after the initial shock of the pandemic, exit rates remained elevated throughout 2021, although they declined significantly in 2022. Entry rates, on the other hand, picked up in the latter half of 2021 and have remained above 2019 levels ever since. Interestingly, during the latter half of 2022 both entry and exit rates were above 2019 levels, indicating more movement both in and out of the labor force, netting each other out. The recent uptick in the prime-age labor force participation rate is due to both an uptick in the labor force entry rate as well as a decline in the labor force exit rate.

The possibility of labor force participation improvements should not have been surprising. As Ernie Tedeschi showed, labor market entry among prime-age workers rose throughout 2015 to 2019, in the aftermath of the Great Recession. This recovery in participation showed no signs of slowing until it was interrupted by the pandemic.

Pre-Pandemic levels are Not the Ceiling

The popular narrative of the post-pandemic labor market was that the recession put a lot of workers on the sidelines, some of them “didn’t come back” for whatever reason, and we’re left with depressed labor force participation as a result. The CPS microdata shows us that while this story was plausible in 2021, with exit rates elevated and entry rates stagnating, things have changed. However, for the prime-age population, labor force entry has remained strong for the last 24 months, with prime-age labor force entry rates above that of 2019 levels.

What recent trends in entry and exit show us is that this wasn’t necessarily the end of the story. For both the overall and prime-age populations, labor force entry rates have picked up and exit rates have declined in recent months. Despite the Fed writing off a rebound in labor supply to bring the labor market “back into balance”, it appears that given a hot labor market and sufficient time, the labor market is capable of bringing in workers off the sideline.

Finally, we should not accept the pre-pandemic level as the limit of what this labor market recovery can achieve. There aren’t any obvious reasons why we should accept the pre-pandemic level for (age-adjusted) labor force participation as our ceiling. New work arrangements such as remote work plausibly lift the ceiling for labor force participation as holding a job becomes more feasible for those traditionally on the sidelines of employment, such as disabled workers. The Fed can — and should — aim higher.