Summary

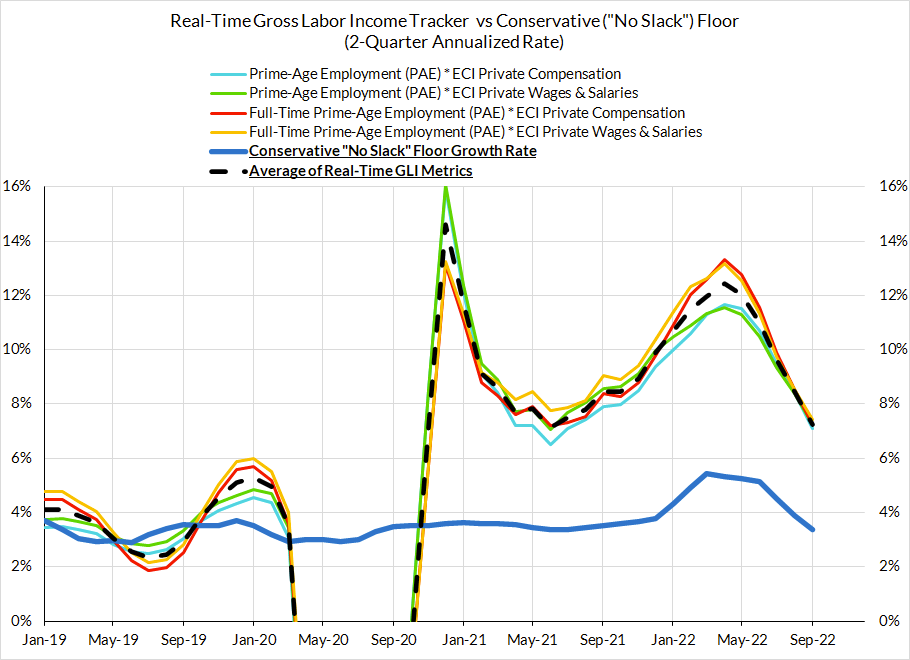

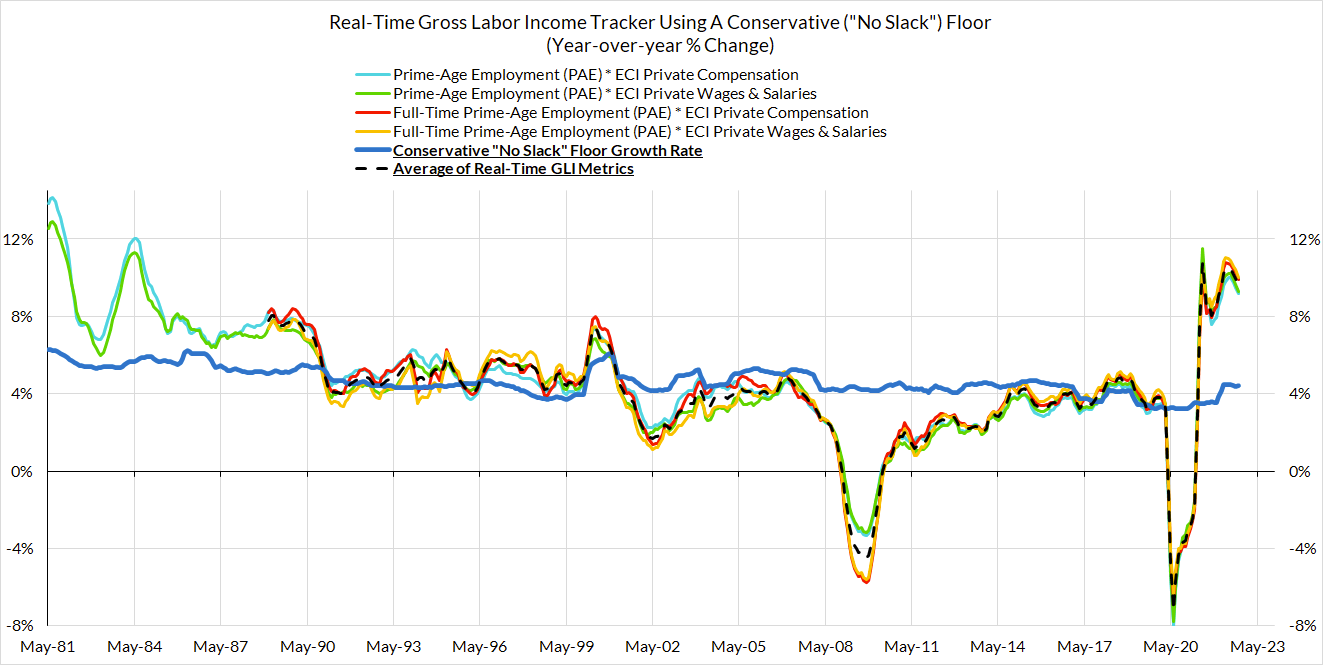

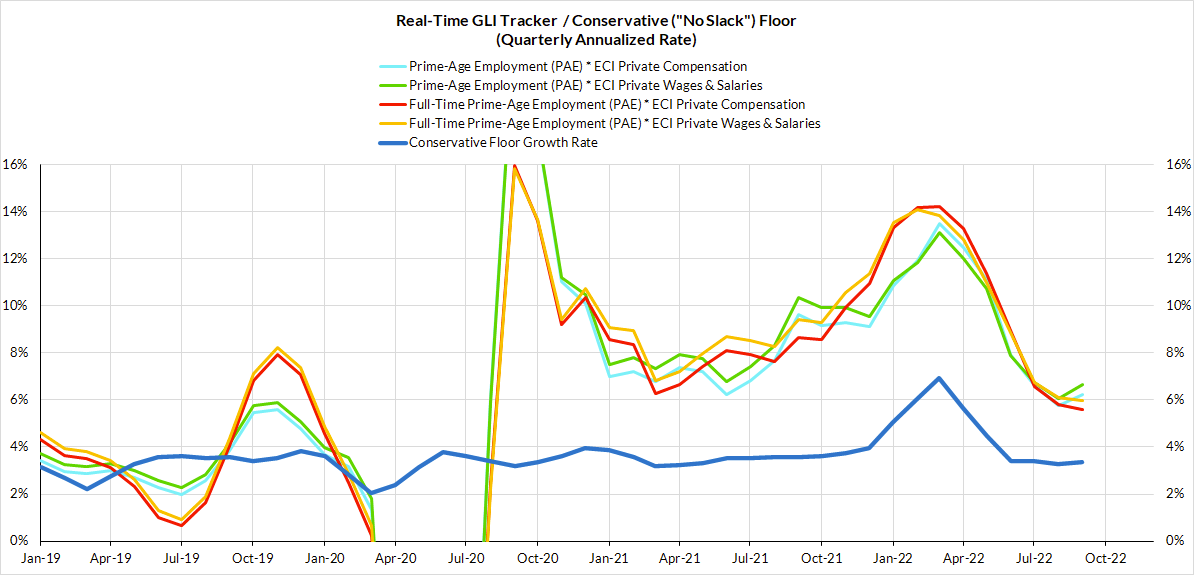

- Friday's Q3 ECI release showed a modest slowdown in the pace of wage growth. Coupled with what we already knew about Q3 employment growth, we are continuing to see a slower—though still highly respectable and resilient—pace of gross labor income growth (~6.1% annualized in Q3 vs ~13.7% in Q1). In the context of our Fed framework, labor income growth is still on track to remain above its conservative "floor" growth rate (~4.4%), and thereby satisfy a necessary condition for the Fed to pursue additional tightening.

- In the absence of a projected breach of the labor income "floor," the rapid pace of current inflationary pressures make ongoing rate hikes justifiable under our monetary policy framework. However, the upcoming FOMC meetings should reflect greater caution about the pace and ultimate scale of additional rate hikes.

- Our framework is more firmly at odds with the FOMC in terms of its 'optimal policy' economic projections—including their attempt to engineer recessionary increases in the unemployment rate. Such rapid unemployment rate increases have empirically foretold more irreversible harm to employment rates and gross labor income growth, especially in the absence of a policy intervention. As is already visible in some of the labor market data, the labor market can "cool down" without resorting to higher unemployment (nor is it clear that the bulk of the price inflation overshoot is proximately caused by labor market conditions).

- At the margin, amplified financial conditions tightening and the ongoing deceleration in labor income growth weaken the case for additional rate hikes under our framework. Both dynamics suggest a weaker outlook for gross labor income growth over the coming quarters, albeit one that still remains above the "floor" growth rate for the time being. The Fed can demonstrate appropriate caution by 1) shifting to a more measured pace of hikes and 2) allowing for more time to evaluate the full effect of realized financial conditions tightening. While the baseline outlook for gross labor income growth remains above the "floor", it can quickly deteriorate. Fed policy is poised to over-tighten in such scenarios.

Our Framework ("Floor GLI") In The Current Context

Back in May 2019, we presented our ideal framework for the Fed to follow when setting interest rate policy [see Figures 20 & 21 for the specified policy reaction function]. In January 2020, we revised the operating set of metrics that shapes how the framework would be operationalized for real-time policymaking purposes.

At the heart of the framework is the trajectory of "gross labor income," which spans both job growth (measured using the Current Population Survey) and wage growth (measured using the Employment Cost Index). As a necessary condition, when the growth rate and level of gross labor income are expected to be sufficient (above what a "floor" growth rate would imply), the Federal Reserve's interest rate policy should be calibrated to manage inflation towards its target. Should that necessary condition for tightening fail to satisfy, policy should be adding support to the trajectory of gross labor income.

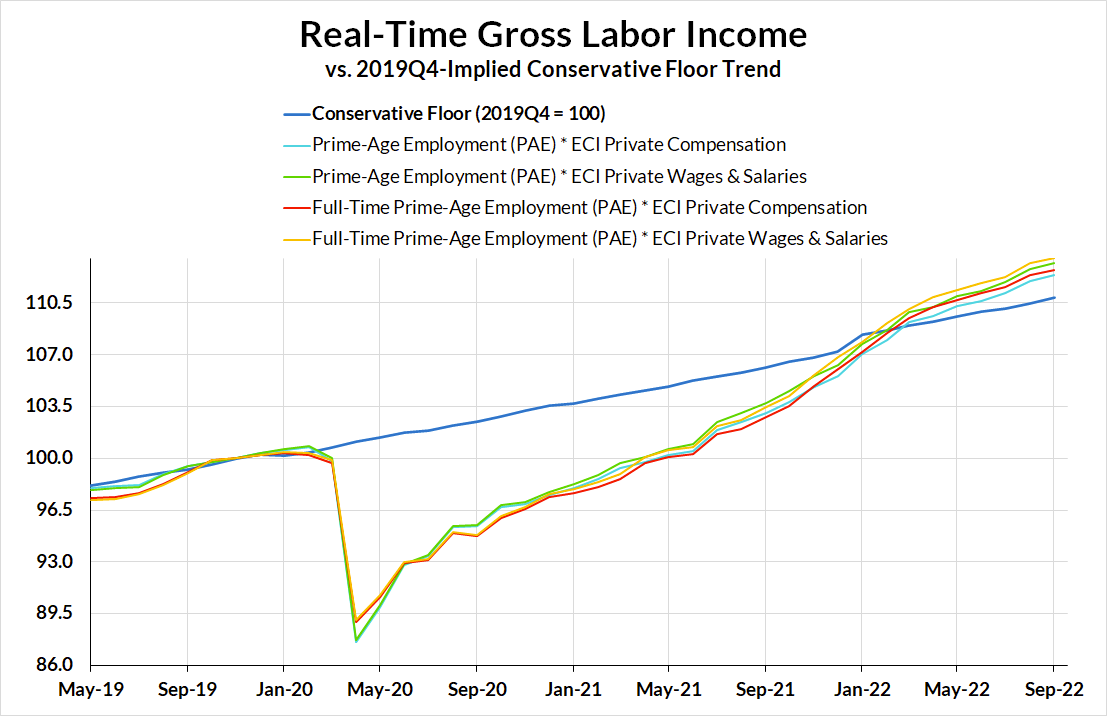

Since the first quarter of this 2022, the recovery in gross labor incomes has been sufficient both in terms of level and growth rate. Relative to when interest rate policy was constrained by the zero lower bound and gross labor income growth fell below its "floor," the trend in our preferred calibrations of real-time gross labor income have more than fully 'caught up.'

Our preferred method for gauging gross labor income in real-time now suggests we achieved a full recovery to the pre-pandemic trend in March 2022.

— Skanda Amarnath ( Neoliberal Sellout ) (@IrvingSwisher) April 1, 2022

This estimate uses a forecast of ECI through March.

For more info on our preferred method, see here: https://t.co/fWobh8f8ns https://t.co/xAvz4OoQ92 pic.twitter.com/HR5DCefMx2

The current pace of job growth and wage growth continue to justify the effort to lower inflation through tighter financial conditions under our framework. So long as job growth and wage growth still show the requisite strength (especially now that gross labor income levels fully recovered back to pre-pandemic trend), our framework specifies elevated emphasis on the "stable prices" component of the Fed's Congressional mandate. We have criticized the indirect and potentially counterproductive nature of the Fed's tools, but we have also been transparent and consistent about what our own framework implies about the direction of Fed policy and financial conditions.

The haphazard and rapid pace of rate hikes this year reflect some questionable management of risks, but the general direction of Fed policy this year was not at odds with the framework we laid out prior to the onset of the pandemic. Income growth has been running strong and so too has inflation; ongoing tightening to lean against those dynamics makes sense. Nor do we see a strong basis for simply revise the framework to adjust to the idiosyncrasies of 2022; revisions to a "framework" should be conducted sparingly and not borne of ad hoc convenience.

The biggest issue we have with Fed policy is not even the realized hikes, but the macroeconomic conditions Fed officials are now transparently seeking to engineer in 2023...

Labor Market Tradeoffs Do Exist, But Need Not Be Cast In Terms Of 'Engineering Unemployment'

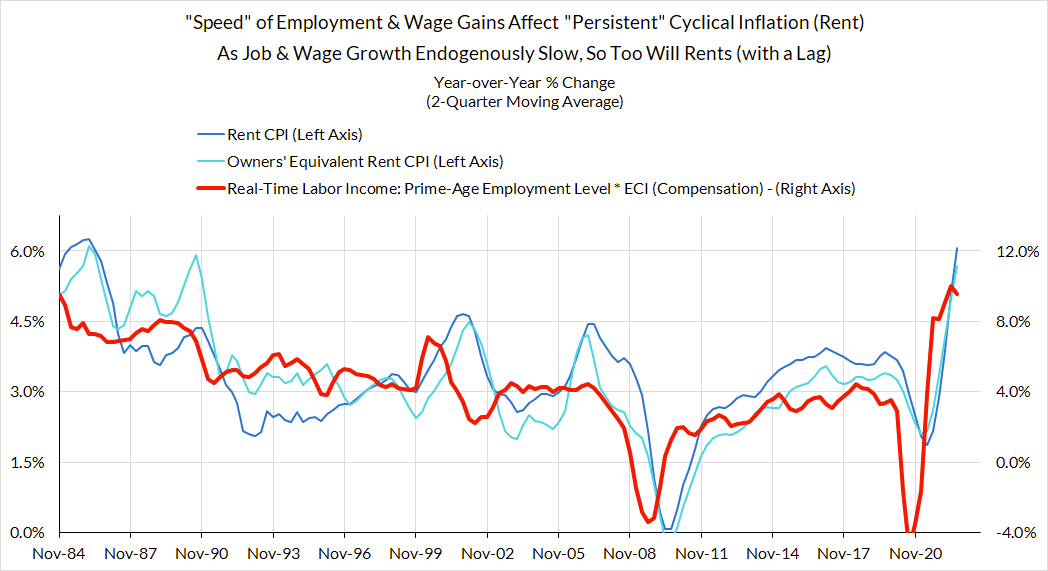

Tradeoffs between the labor market and inflation exist, but also should not be cast in terms of a static Phillips Curve, which inevitably leads to calls for the Fed to engineer higher unemployment to reduce inflation. Unfortunately, the Fed has made it all but clear that they are willing to enable such an outcome over the coming quarters.

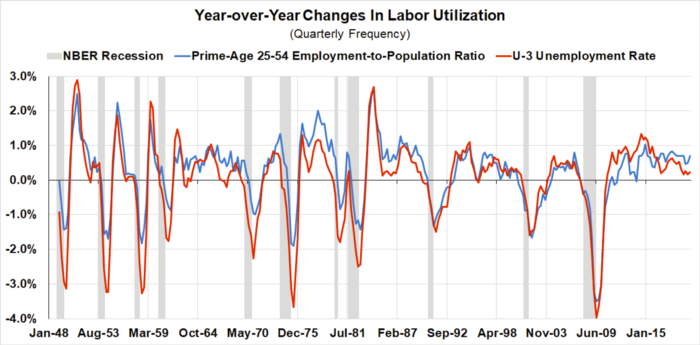

We believe the tradeoffs at play are more dynamic than what a static Phillips Curve tends to imply. The more reliable framing is between the speed of employment and wage gains versus the speed of cyclical price gains (most notably with respect to rent). One can accept a slower pace of employment and wage gains—along with its counter-inflationary benefits—without aiming for outright declines in employment rates.

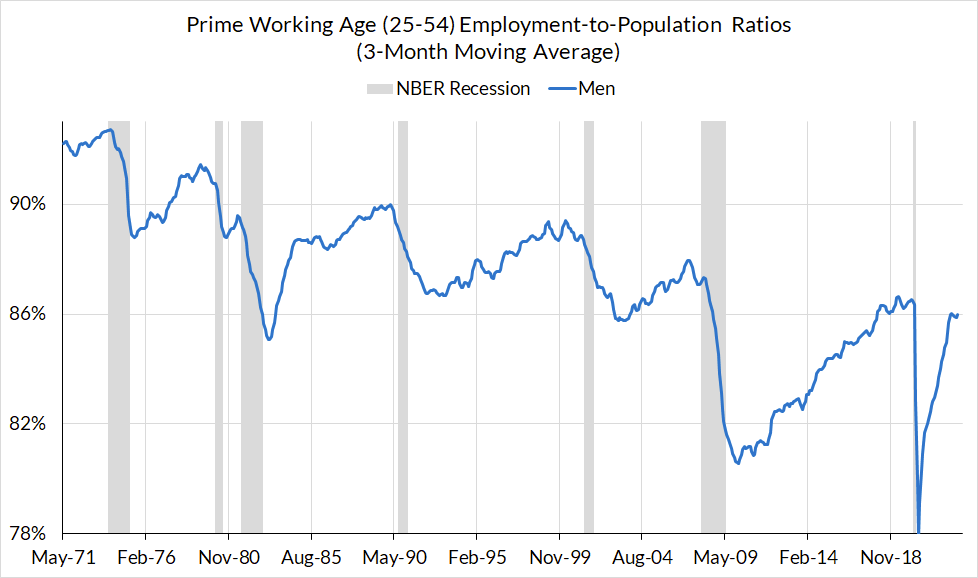

Attempts to claim the Fed should have hiked earlier and faster tend to leave out that such policies would have risked keeping employment levels at their more depressed levels in 2021, leaving millions of prime-working-age persons— employed as recently as 2019—without a job in 2022.

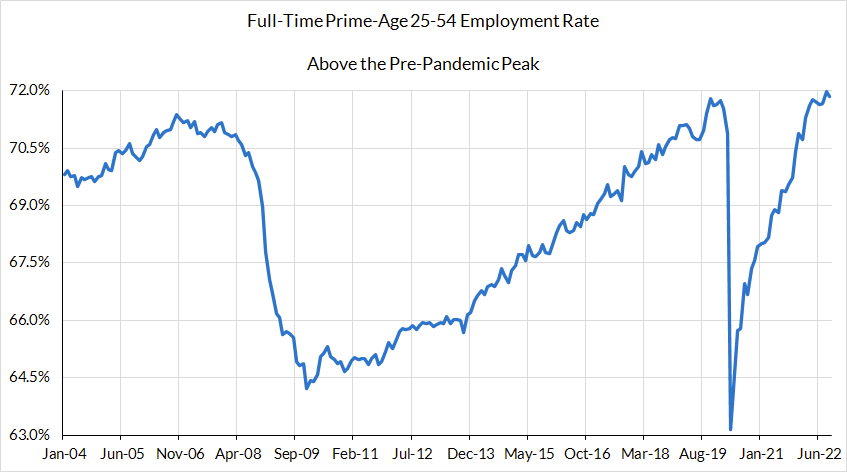

With prime-age employment rates back to their peak 2019Q4 levels and real-time gross labor income catching up to its pre-pandemic "level target" in 2022Q1, the foregone labor market gains from current tightening are more reconcilable. From here, a slower pace of labor income growth carries with it counter-disinflationary benefits, but notably without the risk in 2021 of locking out millions from a job. Merely a slower (but still positive) pace of improvement in employment and wages may prove sufficient and consistent with reducing inflation risks. After a period of breakneck labor income growth (as part of achieving a full recovery in employment levels), labor income growth now has a chance to normalize. Nominal consumer spending growth is more likely to slow; households generally tend to spend in proportion to what they earn.

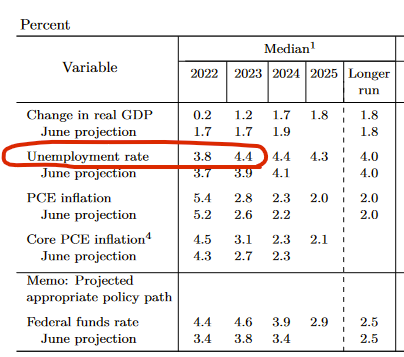

It is highly regrettable that the Fed has stated that the optimal approach to managing inflation risks involves recessionary increases in the unemployment rate. The unemployment rate is currently 3.5% and yet the Fed is projecting a rise in the unemployment rate in 2023Q4 to 4.4%

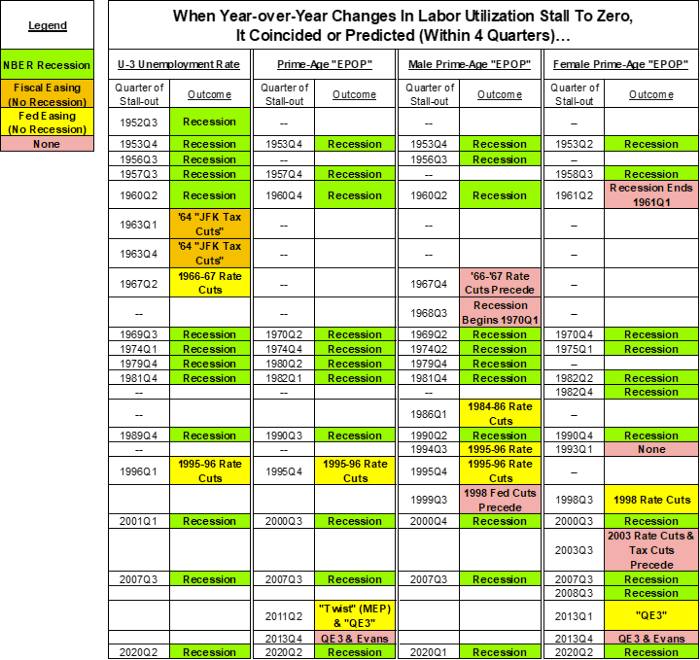

As the Sahm Rule lays out, such a sharp rise in the unemployment rate is empirically consistent with recessionary outcomes, and specifically with respect to labor market outcomes. Unemployment rates that rise fast enough over a short period of time generally foretell much larger and persistent increases in the unemployment rate.

The Fed's own projection of stabilizing the unemployment rate in 2024 seems a little too convenient and firmly at odds with empirical evidence. Labor utilization typically does not stabilize on its own; the exceptions to this rule involve policy interventions that help to stave off further deterioration. Yet the Fed's own projections suggest not to expect any such intervention to stem from Fed policy.

Anyone claiming with high confidence that "the next recession will merely be shallow" might as well sell you snake oil. Recessions are hard enough to predict on their own. The nature and quality of each recession is typically not known ahead of time because business cycles involve path-dependent phenomena. The path to a deep recession starts with an economic contraction. The path to an economic contraction begins with a mere slowdown in growth.

The path-dependence of employment outcomes is especially important to appreciate because the costs of recessionary employment declines are not merely "short run." Prime-age 25-54 employment rates among men are not mean-reverting. They tend to decline sharply in recessions and then subsequently fail to recover to their pre-recessionary peak. With each successive expansion, more of these men, who start out as unemployed, are subsequently classified over time as "not [participating] in the labor force."

The conventional wisdom within macroeconomics is that the welfare costs of recessions and unemployment are merely temporary, while inflation has more permanent costs through how it might re-anchor inflation expectations upward. Yet contrary to popular discussion, there are indeed examples in which inflation surged and fell soon after, without having to resort to surging unemployment. Meanwhile, as prime-age employment among men shows, the more permanent business cycle welfare costs are likely to be related to labor market outcomes.

Intentionally engineering mass unemployment is a morally repugnant approach to managing inflation risks, one that comes with disproportionate welfare costs. It is not obvious that these welfare costs are somehow short-lived. One would have a hard time reconciling the Fed's public strategy of raising unemployment with its Congressional mandate to pursue "maximum employment." There is a better way for the Fed to thread the needle of the dual mandate.

As Income Growth Decelerates and Financial Conditions Tightening Takes Effect, More Caution Is Warranted

Not all rate hikes are created equal. Both the Fed and commentators at-large tend to treat interest rates as a linear tool for managing the economy. Yet financial conditions (mortgage rates, credit spreads, exchange rates, asset prices) can demonstrate inconsistent and nonlinear responses to the Fed's actions. More importantly, economic activity and inflation demonstrates varying sensitivity to the evolution of financial conditions.

Comparisons of the Federal Funds Rate to some imaginary 'neutral rate' can be tempting (for both sides of the debate) but they ultimately reflect an exercise in false precision. It is easier to get the direction right (rate hikes decelerate the economy) than the precise level of the Federal Funds Rate that causes the economy to grow slower than its potential. Right now we have two countervailing dynamics:

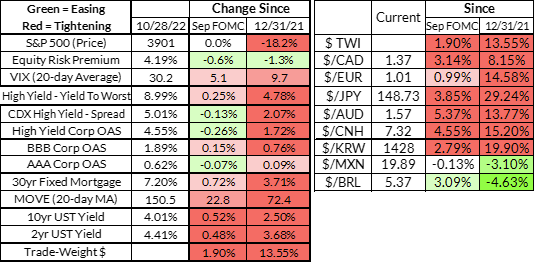

- Financial conditions have largely tightened more than what the 300 basis points of realized Fed hikes this year might otherwise predict.

- Employment and inflation are—thus far—demonstrating more limited sensitivity to the tightening of financial conditions, with housing being the lone exception where a policy effect is reasonably identifiable.

These two dynamics could be reconciled a few different ways. For example, the "real economy" might be more financially resilient as a result of previously expansionary fiscal policy and strong trends in income growth. On the other hand, the effects of tighter financial conditions on real economic dynamics might simply operate with a longer lag for sectors less interest-rate-sensitive than single-family homebuilding.

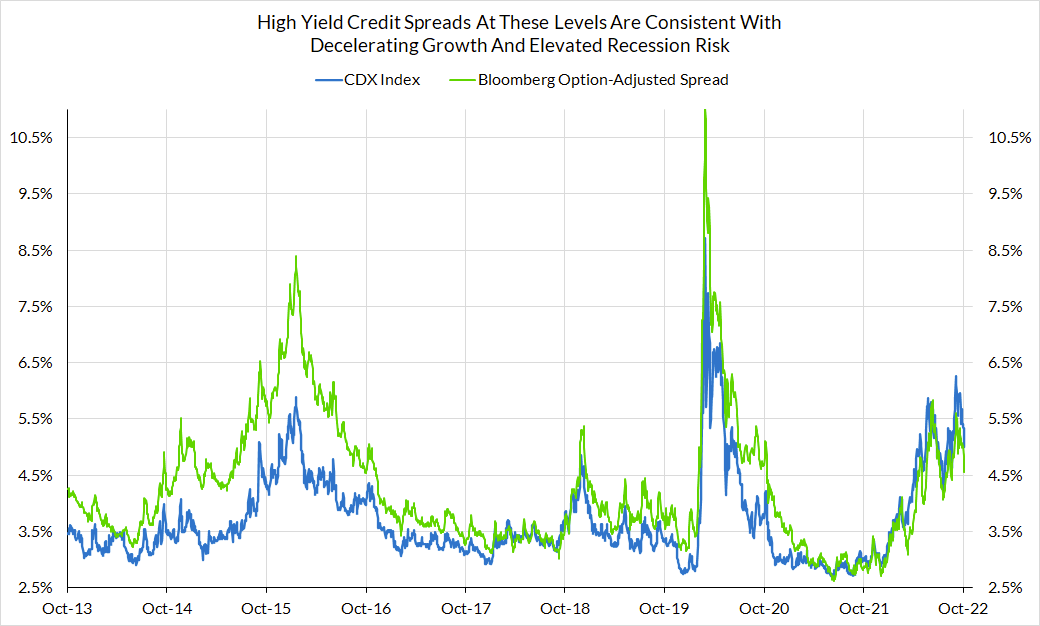

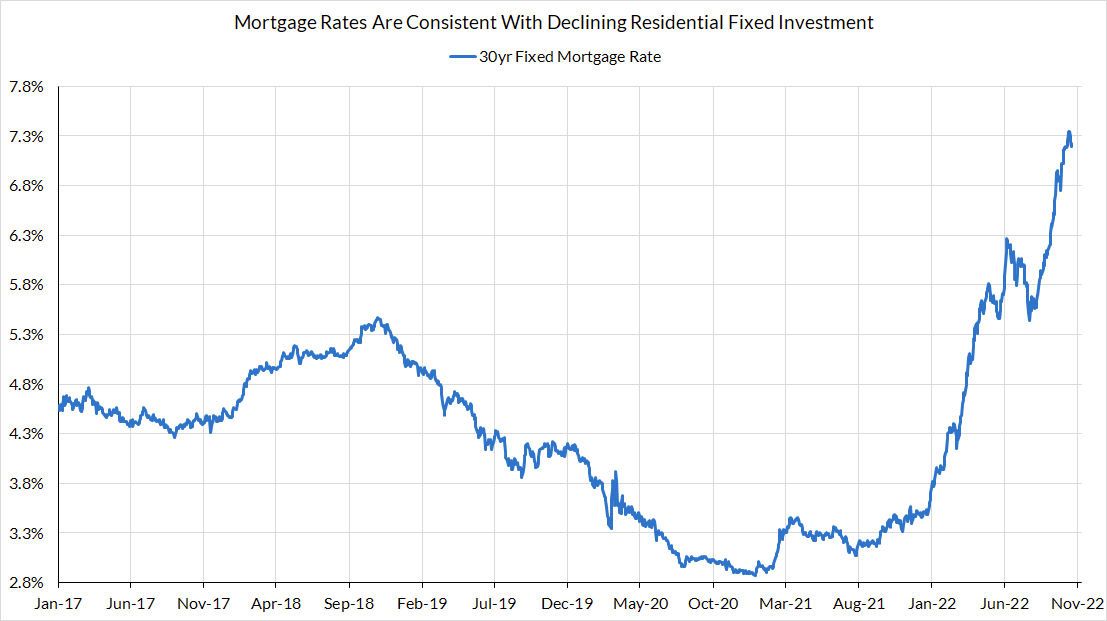

The amplified nature of financial conditions tightening can be seen most visibly across mortgage rates, corporate credit spreads, and exchange rates. Borrowing costs for prospective homeowners and corporations have increased by far more than the 300 basis points of realized hikes to the Federal Funds Rate. Exchange rates are not well explained by cross-country interest rate differentials alone.

Against this backdrop of amplified financial conditions, it is worth noting that the real economic dynamics have been more resilient. Residential fixed investment is poised to be in deep recession in the second half of this year, but this feeds into GDP primarily, not employment or inflation. We have yet to see noticeable evidence that broad-based financial conditions tightening is having broad-based impact...yet.

What we are seeing in the labor market is a highly respectable pace of expansion, but one that appears to be endogenously slowing for reasons that line up with what we previously suggested. As we move past the peak phase of reopening, job growth is cooling. And despite surpassing the pre-pandemic peak for prime-age full-time employment rates, the latest data from the Employment Cost Index does not suggest 'runaway wage acceleration' or a catastrophic 'wage-price spiral.'

What we are seeing now seems more consistent with the "endogenous slowdown" as frictional search costs and one-time hiring impulses abate. A slower growth rate of employment and wages is consistent with a labor market in the process of normalization.

With the risk that realized financial conditions tightening could ultimately "bite" with a lag and the labor market also showing signs of cooling on its own, the case for such rapid rate hikes weakens. Current conditions still justify the Fed's efforts to tighten financial conditions, but they can pursue that effort far more prudently, especially when so much financial conditions tightening has already been priced in.

Rapid 'frontloaded' 75 basis point rate hikes might feel justified when the income growth is historically strong and policy rates are at low levels. But with so much tightening already priced in now, causal uncertainties that surround monetary policy transmission mechanisms point to a more cautious pace of rate hikes, especially now that income growth is showing more signs of slowing. As noted earlier, employment losses in recessions are not easily reversible, and therefore the stakes are high and rising. The Fed can still tighten further should inflation stay high and income growth run strong, but without foreclosing the possibility of a 'soft landing' that avoids outright employment declines. By moving to a slower pace of rate hikes, the Fed will have more time to evaluate the full effect of their policies and avoid the permanent costs of needlessly overtightening.